A scientific paper I recently encountered set off an intriguing line of thought about our reactions to art and artists. Let’s start with the obvious fact that artists are people, and so some of them are lovely folks with good values; and some are jerks. Should our assessment of the artist as a person color how we think about their artistic productions themselves? The article I read starts with a striking finding. The authors, Joe Siev and Jacob Teeny of the University of Virginia and Northwestern University respectively, surveyed 634 cases in which university faculty had been punished for some type of sexual misconduct, and went through an elaborate rating process to assess, first, how serious the transgression was, and, second, how serious the punishment was.

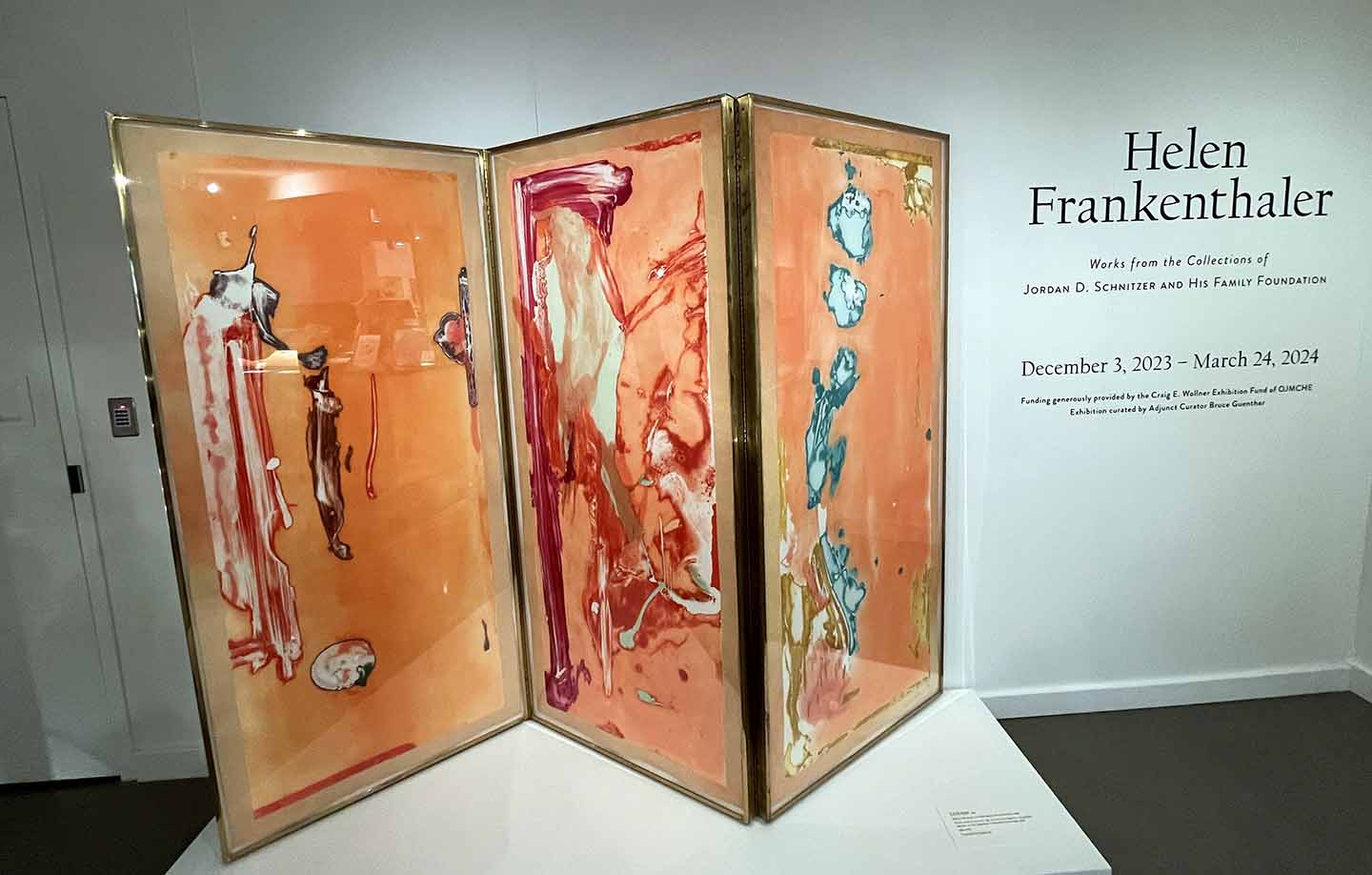

Helen Frankenthaler Skywriting (1997)

Skipping all the details, the blunt finding is this: at whatever level of transgression you choose, the artists received more extreme punishment than scientists. Specifically, the average level of punishment for the artists included the fact that they were suspended, or placed on leave, or their contracts were not renewed. For the scientists the average level of punishment was less severe. Honors were revoked or salaries reduced, but they were less likely to lose their jobs on average.

Helen Frankenthaler Free Fall (1992-93)

What is going on here? The authors of the paper offer the suggestion that, for artists, we cannot easily separate their professional output (their paintings, sculptures, compositions, etc.) from who the person is. This notion is rooted in the idea that artists’ output is, in important ways, a reflection of the artists’ emotional makeup, their perspective on the world, and their personality. For scientists, it is proposed that we can more readily separate who the person is from what they do professionally. Presumably this is a reflection of the assumption that scientific work is more likely to be objective, more likely to be governed by rigid rules about procedure and analysis, and in all of these ways just less personal. The authors therefor propose that a process referred to as moral decoupling, the ability or willingness to sever the work from the person, applies to scientists more readily than to artists.

Helen Frankenthaler CEDAR HILL (1983)

I worry that this explanation to some extent mythologizes how scientists work. I also worry, that there may be other ways to think about the data. (The article lists multiple follow-up experiments designed to exclude alternative explanations, something I do not have the space here to discuss.) And note: the contrast between artists and scientists disappears if the moral transgression is directly related to their work, for example an instance of outright plagiarism or fabrication of data. These work-related offenses costs scientists as well.

Yet the upsetting fact of differential punishment for the respective professions remains, and is troubling in a number of ways. As one concern, it raises questions about inequitable treatment, when some professional commits some moral offense. But the result also invites questions about whether we can, or should, separate our evaluation of the artist from our evaluation of their work.

Helen Frankenthaler Spoleto (1972)

One famous example is the huge condemnation of Woody Allen for his misdeeds, a condemnation that has led essentially to a boycott of his movies by many people, myself included. It is interesting to ask, whether this condemnation leads people to believe the movies themselves are less good, or whether the experience of watching a movie by Allen has itself become distasteful (I come down on the latter explanation.)

I wrestle with these issues in my own approach to certain art works and artists. For example, I took off my walls work by Emil Nolde, someone I had revered since childhood and had personal connections to, once his moral transgressions as a supporter of the Nazi regime, NS philosophy and virulent anti-Semitism became clear. (I wrote about all this previously here.) Even though my assessment of his work product, his art, has not changed – I still consider it brilliant – the man and the work have been canceled in my house. I simply refuse to be reminded of the betrayal.

Similarly, I had recently written a long diatribe in these pages in favor of canceling Salvador Dali, unable to decouple his work, still considered amazing, from the moral failures of that artist.

Helen Frankenthaler Westwind (1997)

Then again, I continue to listen to Wagner, even though he embraced Nazi ideology and was generally a pretty wicked human being. It is a guilty pleasure, listening to something that should be ignored if I were only true to my own standards. Not exactly a principled approach.

The possible connection between artist and their output was also felt in my reaction to the works on display in today’s photographs, the prints of Helen Frankenthaler currently on view at OJMCHE. Let me hasten to add I know of nothing she has done wrong, in sharp contrast to Nolde, Dali or Wagner. I just know that she was in a 5 year relationship with a critic who I despise for political reasons. I also know that she very much tried to make her mark as a woman in a field then dominated by men, even though her talent towers high over many of them. These bits of background information colored the way I read her prints, and how I experienced her work in ways that struck me as a tad too demonstrative and intellectually constructed (with one exception, a flowing print I really liked, below.) (For a positive, learned, detailed review of the show by my ArtsWatch colleague Laurel Reed Pavic, go here. I should also add that Frankenthaler’s work is incredibly beloved by most viewers. I seem to be the odd person out.)

I wonder how I would have reacted to the work if I had no idea who produced it.

Helen Frankenthaler Flirt (2003)

In sum, I wish I had a clear vision of why I canceled Nolde, but continue to regard Wagner’s music as tolerable even if listening to it has to be acknowledged as a guilty pleasure. These are mysteries to contemplate. In the meantime, and consistent with the article I discussed, it’s plain that, at least some times, I am unable to separate my views of the artist from my reactions to the work. Why this happens, and why there is inconsistency in how this plays out, remains to be answered.

Helen Frankenthaler Untitled From What Red Lines Can Do (1970)

Music today is in memory of a brilliant talent who died today 8 years ago. No guilty pleasure here with his last album, just pure, unadulterated longing that David Bowie could have lived and made music a little longer.

Lee Musgrave

Very engaging topic … of which I have a variety of reaction to.

First, art faculty are fired quicker because there is a vast array of potential replacements instantly available, which is not so in the sciences.

Second, very few people can be considered all bad or all good. We all are a mix of both and in my opinion that is what makes us human.

Sara Lee Silberman

I am not remotely a connoisseur of Helen Frankenthaler’s work, but I enjoyed the “show” you provided here.

And yes, the underlying issue of this piece is interesting, and I find myself just as inconsistent in my applications of the principle as you cop to being….