IT SEEMS TO BE the rule these days: every time I visit a new exhibition at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education (OJMCHE,) my brain picks up speed and my heart gets either heavier or lighter, depending on what’s on display. The most recent visit changed my mind as well. Last month I had declined to review the opening exhibitions in celebration of OMCHE’s expansion and addition of a new permanent gallery dedicated to Human Rights after the Holocaust. I did not want to mingle with crowds, which I very much hoped would be there to honor the museum’s continuing growth. I was spoon-fed on Rembrandt as a child and was not sure I needed to see yet another etching of biblical lore in my life time. And, most importantly, the recent loss of Henk Pander, a close friend, still felt raw. I had written an in-depth review of his penultimate exhibition, The Ordeal, while he was still with us and was not sure if I had anything more to add.

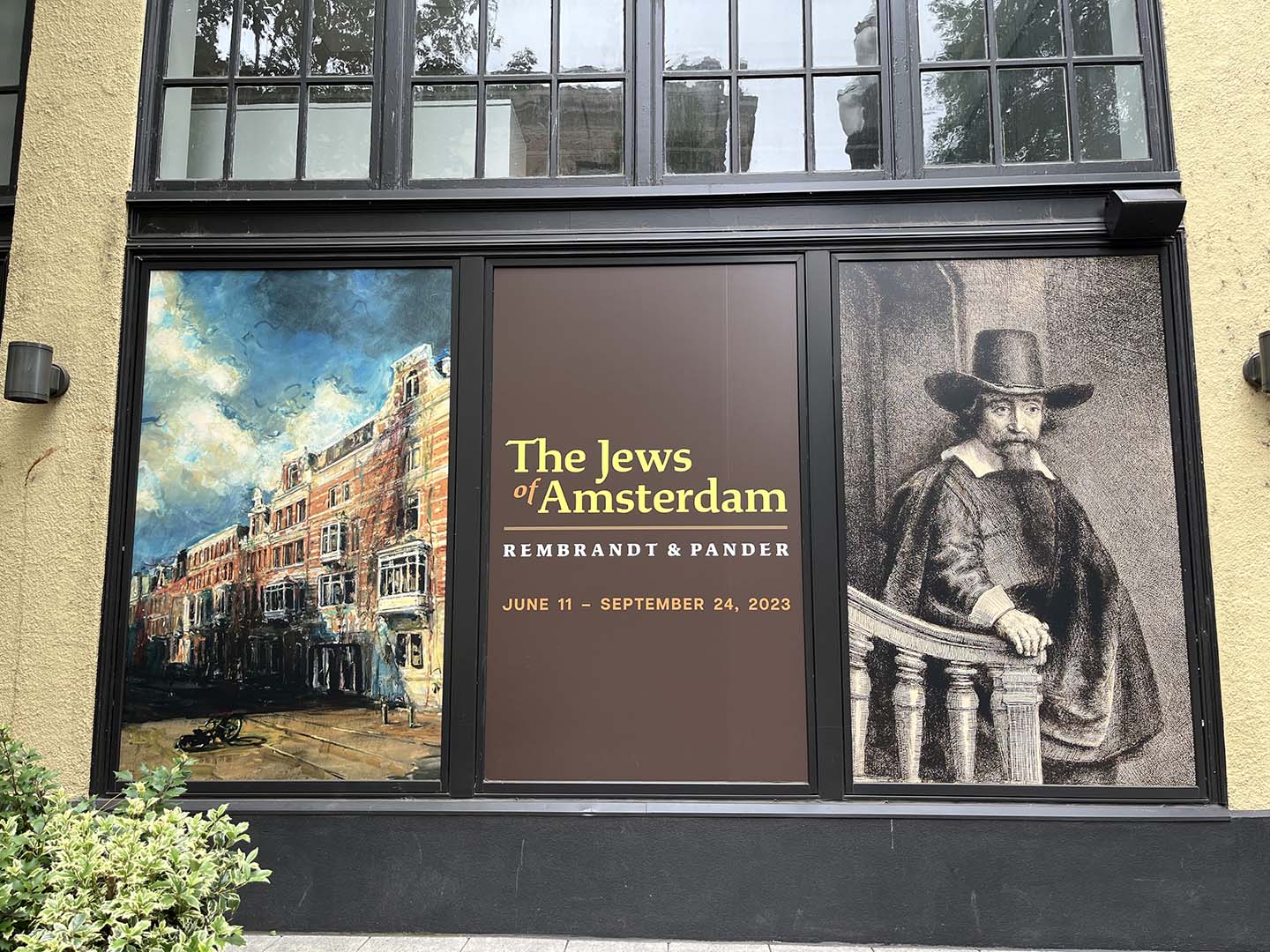

Well, here I am, reviewing after all. The exhibitions were just too interesting and raised important questions while I walked through a thoughtfully curated show during an afternoon when the galleries were empty, trying to put a lid on my unease. Taking in The Jews of Amsterdam, Rembrandt and Pander, as well as But a Dream, Salvador Dalí, turned out to be a challenge on multiple levels, if a rewarding one. That’s what good museums do, right? Make you think and feel and learn, even when some of the topics are difficult to deal with, as has been the case for the majority of the exhibitions I have reviewed for OJMCHE over the last years.

Want to stick with me then, while I’m thinking out loud? (Alternatively, here is a detailed OR ArtsWatch review of the museum re-opening, including Bob Hick’s conversations with museum director Judy Margles explaining some of the choices made, and Bruce Guenther who brought his perceptive touch once again to the selection and arrangement of exhibits.)

Let’s start with the Dalí. It was a bit surreal to enter an exhibition of 25 works, “Aliyah, the Rebirth of Israel,” commissioned by Shorewood Publishers in 1966 for the 20th anniversary of the founding of the State of Israel and mounted in observance of the state’s 75th birthday, when I had read just hours earlier a statement by former Israeli Prime Minister and decorated military officer Ehud Barak in Haaretz: “The moment of truth is upon us. This is the most severe crisis in the history of the state. … with the upcoming vote… we are hours away from a dictatorship.”

Aliyah literally means ascent, but has been the term used for the return of Jewish people to a land they claim their own. Seeing the internal divisions, violent protests, an increasingly desperate fight for democracy and a country accused by B’Tselem, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, among others, of practicing apartheid against Palestinians, one can’t but think of descent rather than ascent. Isaac Herzog, the President of Israel, warned of civil war as Netanyahu rejects compromise. Organizers estimated 365,000 people have come out in cities around the country on one day alone to protest the government’s attempted judicial overhaul.

All the more a reason, one could argue, to present a vision of Israel that helps us understand its history, depicts its travails, and confers hope and admiration about the resilience of a people. And how better to accomplish this than with photolitographs based on masterfully executed mixed media paintings, grouped around relevant Zionist history and elucidated by biblical citations at times? (The paintings were displayed at the Huntington Hartford Museum in New York City originally, and then sold; the current whereabouts of many of them are unknown.)

There is just one problem: the artist, Salvador Dalí, was an abominable human being, and his expressed admiration for figures like Hitler and Generalissimo Franco at least indirectly suggest racist and authoritarian preoccupations. Whether he actually was an antisemite is a matter of debate, one the museum, to its credit, does not entirely shy away from. David Blumenthal who, together with his wife, lent the current exhibits to the museum, engaged in serious scholarship around the question of Dalí‘s relationship to Jewish themes, laid out in an essay here. He went through a number of speculations to reject most of them in favor of the conclusion below, with a lingering doubt about motives nonetheless:

So, what was Dali’s commitment to “Aliyah, The Rebirth of Israel”?

It seems to me that it was not an obsession with moneymaking or a desire to develop the “Jewish market.” Nor was it a need to rectify his reputation as an antisemite that brought Dali to use Jewish themes. It seems to me, too, that it was also not a quirk of his or Gala’s ancestry, or sympathy with Jews, Jewish culture and history, or the Jewish State. Rather, as I see it, this was a commission and Dali executed it seriously. Shoreham had commissioned this. Dali had Jewish friends in New York who helped him with the material, though we do not know who these friends were …This, it seems to me, is the most reasonable explanation for Dali’s work on “Aliyah, the Rebirth of Israel” – that this was a serious execution of a serious commission, authentic even if not experimental — though the argument of crass exploitation cannot be ruled out.

***

SHOULD WE SEPARATE the art from the artist? Can we?

On the one hand, we have decisions like Israel’s to deny public performance of Wagner’s music, a composer associated with expressed anti-Semitism and admiration of totalitarian rulers, who adored him in turn. On the other hand, if you look closely, antisemitism was such a run-of-the-mill sentiment across continental Europe that we would have to throw out half of all famous writers and composers, just thinking of Bach, Beethoven, Robert Schumann and Clara Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky and Carl Orff. In literature we couldn’t read Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice”, Dostoyevsky, the poetry of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, to name just some who come to mind readily and all of whom are performed in Israel or read in Hebrew translation. It is, of course, not just a question specific to antisemitism, but one that extends to any repulsive behavior. Do we patronize the movies of a Roman Polanski or Woody Allen, or watch Bill Cosby or Johnny Depp? Do we listen to music by people who have been convicted of various forms of abuse? Do we buy our grandchildren books authored by newly rabid transphobes, even if the literature enchanted entire generations of our own kids?

In some ways, we have to do our homework to decide if a given artist held odious attitudes, or whether there was a deeper, darker impulse at work that really could be tied to evil that manifested in expressed cruelty, both verbally and behaviorally. (Read George Orwell for the details.) For Dalí, some still re-interpret his glorification of fascism, whether Hitler or Franco, as a defiant provocation of his surrealist peers with whom he competed (it did lead them to exclude him from their group, clearly seen as more than just big talk.) But if we look at the witness reports on his violent beatings and sexual assaults of women, torture of animals, necrophilic longings and, expressed admiration (“Hitler turns me on to the highest, Franco is the greatest hero of Spain”) in his book The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí, there seems to be enough to decide that he was not just trolling, and thus we do not want to give him and his work more exposure. In fact, read his previously unpublished letter to Andrew Breton, and I bet you will never look at this artist with the same eyes again.

So why do we give the artist a platform? And I don’t just mean the museum folks who make decisions about what would fit into a particular exhibition series embracing art with a Jewish theme, or celebrating Israel’s birthday, or attracting visitors with the lure of famous names, visitors who then learn about Judaism, or truly intending to open the debate about art vs. artist. I also think of the rest of us, who flock to see the famous artist’s work. The simple answer might be: we are interested in the art, admire it, so who cares about the artist, live with it! There are more complicated answers, though. One potential reason could be that our own attraction to spectacle, our hidden desire to make excuses for wanting to witness violence or narcissism in action, can be satisfied if we have something that “justifies” the behavior we observe or unconsciously lust after (think crowds at lynchings, for example.) This something, in the case of artists, can be the belief that “genius” excuses a lot. In a new book, Monsters. A Fan’s Dilemma. author Claire Dederer argues that “genius” is a construct that implies that the artist channels a force larger than him/herself. We give them a pass because that force, the artistic impulse, is so overwhelmingly positive that it makes up for the rest of the sorry picture. This presumed force larger than someone can, of course, be attributed to multiple origins, like when you believe that certain powerful people (and I won’t mention any names) are sent by a deity or fulfill biblical prophecies, and thus have carte blanche to overstep moral boundaries for that very reason.

Another possibility arises from brand new research findings from psychologists at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany. The research team tried to explore empirically how people’s knowledge of abusive behavior by an artist would influence their aesthetic judgement of a piece of art as well as their electrophysiological brain responses. The shortest summary of a very complex and smart experimental design I can offer in our context: receiving negative-social biographical information about an artist will make you like their art less. Yet at the same time the work is physiologically more arousing to you, particularly if the art itself contains a reference to the negative behavior, when you look at our brains’ first spontaneous reactions. Reverberations of disgust? Or the kick of a voyeur?

Independently, we also have to differentiate between those who suffered from an artists’ immorality, Holocaust survivors who had to play Wagner in camp orchestras, or domestic violence survivors who watch a movie star strutting with impunity, compared to those of us for whom this is more of an intellectual enterprise. I have no answers. I know some of the art I love most or that has formed me in my understanding of art was created by people I dislike or even abhor. Dalí‘s art does not belong to the former, but Dalí the person surely resides amongst the latter. I would not ever go to see an exhibition solely presenting his work, being firmly convinced of his embrace of fascism among the rest of his abominations. I was in luck, then, that the remainder of the afternoon provided a much brighter picture, with The Jews of Amsterdam, Rembrandt and Pander.

***

“A new and astonishing poetic secret arose from the idea of juxtaposing related, as opposed to unrelated, things.” René Magritte, 1932

***

WHEN I ENTERED the gallery showing Rembrandt (1606 – 1669) and Henk Pander (1937 – 2023) – neither one of them a Jew, so the title needs a bit of stretching – I couldn’t help but think of Magritte’s 1932 painting Les Affinités électives (Elective Affinities). What triggered the memory was the spatial feel of Rembrandt’s etchings contained in a small, compact space, with little room to breathe, surrounded by the proverbial as well as literal walls of Pander’s paintings lining the perimeter, just like the egg in the cage.

But the combination of the two artistic oeuvres also fit perfectly with Magritte’s musings above, by all reports offered when he had finished this painting after having woken from a dream in a room with a caged bird. The typical surrealist approach of combining unexpected and unconnected subjects to surprise effects had been replaced by a play on relevant relations. The notion of elective affinities was originally coined in a novel by Goethe (Die Wahlverwandschaften), but more likely read by Magritte, sympathetic to the communist party for most of his life, in Max Weber’s 1905 book The Protestant Work Ethic and Capitalism. The term was loosely understood as a process through which two cultural forms – religious, intellectual, political or economical – who have certain analogies, intimate kinships or meaning affinities, enter in a relationship of reciprocal attraction and influence, mutual selection, active convergence and mutual reinforcement.

Henk Pander Intersection in Amsterdam East (Set back in time) 2022

There you have it: The painters’ works do relate, converge and reinforce each other, no matter how far apart in style, historical content, execution. Central to both is, in my opinion, a shared focus on what Robert Frank so famously called “the humanity of the moment.” (For him this was a requirement for a good photograph, and he went further: “This kind of photography is realism. But realism is not enough – there has to be vision, and the two together can make a good photograph.”)

Beyond the shared location of Amsterdam, both artists’ output is undisputedly visionary, creating imagery that stands for key moments in the exploration of humanity’s history, whether guided by the episodes derived from the belief system of the (mostly) Old Testament (Rembrandt,) or the photographs taken of his Dutch surround and rendered into historical narratives that represented the desolation of a town under Nazi occupation (Pander.) The humanity of the moment is captured by Pander most vividly in the absence of same, not a person in sight, just left-over detritus hinting at deported burghers, violent actions and hasty departures, (and conveniently setting scale, so that the already ominously lit buildings, some seemingly on fire, take on an imposing height that intensifies the sinister mood. (I am adding a contemporary photograph from some tourist website that shows how small the houses actually are.)

Henk Pander Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam (2022)

The humanity in the moment that is not directly accessible in the pictures because it belongs to the artist more than the subject, is Pander’s homesickness while he painted the streets he once roamed, (a homesickness that one has to assume was shared by the deported Jews who survived the Holocaust.) Henk suffered recurring waves of Heimwee, the Dutch word translated as the aching for home, better capturing a real sense of almost physical pain, rather than a general malaise. It was not nostalgia, after all his childhood had been harsh under German threat and occupation, hungry and consumed with fear. It was not Verlangen, longing for an imaginary golden past that never existed. It was the loss of a sense of place and familiarity with that place, familiarity with a culture, language and certainly the spot in a family tree of many generations of painters descending from the old Masters. He was proud of having come into his own as a mature artist with his very own ways of expression, but also felt like a stranger in a strange land, no matter how much recognition he received or how truely in love he fell with the American landscape of the West.

Henk Pander (Left) Kraaipanstraat, Amsterdam (2019) (Right) Weteringschans, Amsterdam (2018)

I vividly remember an occasion where I tried to come up with an interpretation of one of his large oil paintings (not in the current set.) After repeated failures he said, with that impish grin of his’, “it’s just a painting, Friderike!,” which it was and yet wasn’t. They all were, in the sense that often some visual exploration, purely guided by aesthetics, started to take over, intermingling with or even overshadowing the original concept. But there was always a concept, a thought, a communication of something that deserved our attention. A day later I sent him a postcard of Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s painting The Dutch Proverbs as a tease, a painting capturing some 120 concepts all in visual guise, conceptualization on steroids. We explored it together, during one of the long waits in the clinic where I drove him for early cancer treatments long before the pandemic ensued, and were able to identify many of the proverbs which are very similar in German and Dutch. Heimwee descended on both of us, knowing that no-one in our immediate vicinity would know even a few of the proverbs, which were such cornerstones of our childhood.

May his memory be a blessing.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder The Dutch Proverbs (1559) Oil on Oak Panel, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

***

Voor de wind is het goed zeilen – it’s easy to sail ahead of the wind – If conditions are favorable it is not difficult to achieve your goal.

The little boat in the upper right corner of Brueghel’s compendium embodies this proverb, and it applied to Rembrandt van Rijn’s life and career for many years. Until the winds shifted, when he ended up losing his patrons due to changes in public taste, losing his house and belongings in bankruptcy, and after some more artistically productive years was eventually buried in a pauper’s grave near Amsterdam’s Westerkerk in 1666. As is so often the case, the decline was overdetermined, with multiple factors at work, including financial miscalculations of not having paid debts and overspending for his compulsory collecting of art and antiquities.

Much has been written about the artist, with unlimited admiration or sanctimonious scorn. A genius outsider, for some, making his way from humble origins to the embrace of a wealthy merchant class, a misogynistic exploiter of women, for others, who confined his aging lover who had raised his orphaned son to a prison-like asylum when she started making demands while he was already bedding a 23 year old replacement. Myths about him having secretly adopted Judaism abounded. Hitler and his charges tried to make him into an Aryan hero (and looted his art during the war), to the point where they appointed the horrid propaganda film maker Hans Steinhoff (Hitlerjunge Quex)to make a movie about him in Amsterdam in 1941 with a script appointing three “evil Jews” as the cause for his downfall, with Propaganda Minister Goebbels covering all the cost. (The Dutch Resistance Museum in Amsterdam had a fascinating exhibition about Nazis’ attempt to incorporate the Rembrandt into fascist ideology in 2006.)

Ephraim Bonus, Jewish Physician (1647)

The best introduction I can think of, one successfully arguing that the artist was simply a man of his times, acting within an era-specific and location-determined set of conditions, is historian’s Simon Schama’s book Rembrandt’s Eyes. (For those of us with a shorter attention span, here is a link to a talk he gave that really sums up a lot of information. It is open source and you can download the whole thing.) Schama stresses the general attitude toward Jews in the Amsterdam of the 17th century as one of “benign pluralism.” Of the 200.000 inhabitants in 1672, only 7500 were Jews, with the minority of very wealthy Sephardic Jews (Marranos, forced converts to Catholicism) who had fled the Southern Inquisition at the beginning of the century concentrated in one area, and 5000 much poorer Ashkenazis who by 1620 fled the programs in central and Eastern Europe, speaking Yiddish and keeping to themselves.

The Jewish Quarter, where Rembrandt lived for some twenty successful years had a 40/60 % mix of Gentiles to Jews, with the Sephardic Jews enjoying social equality (although not intermarriage) while enormously contributing to the country’s economy. It was, early on, an exceptionally tolerant age and society, of which Rembrandt was no exception. Again, it is somewhat surreal that I write this while the Dutch government has collapsed over issues of asylum seekers and immigration policies, with a fragile 4-party coalition under Prime Minister Mark Rutte, lasting, in this round, less than 18 months. An extreme right wing party, the Party for Freedom under Geert Wilders, and a populist Farmer-Citizen movement, headed by Caroline van der Plas, are eagerly waiting in the wings for the potential November election. Tolerance for immigrants is at an all time low, making the 17th century look ultra-liberal in comparison.

Rembrandt used some of his Jewish neighbors as models, although it is debated how often, and was often interacting, perhaps even close friends, with Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel, an emphatic proponent of reconciliation between Jews and Christians who commissioned multiple works from the artist, some displayed in the current exhibition. Some might have simply been observations outside his window. It is now claimed that the setting of the artist’s 1648 etching, Jews in the Synagogue (1648) – is not a synagogue but, rather, a street scene in the Jewish Quarter of Amsterdam. It shows only nine Jews, one less than the requisite minyan, but it also centers an isolated figure, potentially remarking on the separation between the established Sephardic Jews, and the Ashkenazi newcomers.

Jews in the Synagogue (Pharisees in the Temple (1648)

Rembrandt’s tolerance or even desire for inclusion extends beyond the Jews to people even lower in the social hierarchy of the times: Blacks. I think this is important to acknowledge, since it describes the artist’s willingness and need to depict the world as it was, forever searching for veracity and empathizing with the human condition.

He created at least twelve paintings, eight etchings, and six drawings in which Black people play roles as spectators or participants in biblical scenes, models likely taken from the street or the household of his Jewish neighbors. (Ref.) As it turns out, the Creole were former slaves on the plantations of the wealthy Marranos, brought back as household help and now just servants since slavery was prohibited in the Dutch provinces. The rich Portuguese Jews were quite involved in the sugar trade, colonial exploits pursued by the Dutch West India Company (WIC) that by 1630 fully engaged in human trafficking to ensure there were laborers for the mills and plantations in the colonies. (Quick aside, I know it’s getting long: acknowledging the specter of colonialism and slavery, museums and art historians have ceased to talk about the era as the “Golden Age.”) Rembrandt must have known this, particularly since he had portrait commissions of some of the most influential Marranos who owned plantations in Brazil. But the fact remained, he depicted his Black subjects without disdain or mockery and gave them central roles in biblical narratives that might have emphasized the possibility of conversion (proselytizing then often used as a justification of slavery.)

If you look at the intimate, small depictions of biblical scenes, or Jewish citizens engaged in religious practice, one thing is clear: not only are people naturalistically depicted, truly as they looked, but they are always caught in a narrative moment that draws the viewer completely in with its drama and impending resolution – the humanity of the moment. That moment is one where things turn, either for good or for bad, the moment before the sacrifice of a son,

Abraham and Isaac (1645(

the moment of receiving forgiveness,

The Return of the Prodigal Son (1636)

the moment of the take-off of the angel, barefoot, no less, and with a gravity-proof robe

The Angel departing from the family of Tobias (1641)

the moment a dangerous seduction might or might not happen.

Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (1634)

Rembrandt and his compatriots focused in this work on the fragility of our existence, caught in the very moment where something irreversibly changes, never to be the same again, often raging at the claimed inevitability of it all. As I wrote previously while reviewing Henk’s work, the Dutch have a name for that circumstantial reversal, staetveranderinge, a term derived from the Greek word peripeteia, and a concept embraced in Dutch paintings since the 1600s. The change could be in any direction – from anguish to praise, like in Rembrandt’s versions of The Angel appearing to Hagar, but most often captured when circumstances shifted irrevocably to disaster, like Jan Steen’s Esther, Haman, and Ahasuerus from 1668, below.

The preoccupation with “state change” corresponded with the rise of Calvinism, a religion that dominated the Dutch provinces and led to long religious wars against Catholic nations but also to boundless prosperity, shaping the evolution of commerce and empire. Henk Pander certainly inherited and made good use of this narrative concept across his life time, but Rembrandt knew to convey it to perfection. This is how he captures our rapt attention, since we know and fear these situations and are curious to see how they will be resolved, unless we know the biblical stories or re-tellings of mythology by heart, which have, at least in some instances, a good ending, something that hooks us as well.

Selection of illustrations for Menasseh ben Israel’s “Piedra Gloriosa” (1655)

Story tellers, the both of them, across time and historical settings, working magic with light, shadow or color, willing us to be a participant in the solving of the narrative. Simon Schama’s assessment that Rembrandt managed to engage us by upping the intensity of the story through combining the ordinary with the extraordinary holds for Henk Pander as well.

See for yourself. The exhibition will last until September 24, 2023.

***

OREGON JEWISH MUSEUM AND CENTER FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION

- 724 N.W. Davis St., Portland

- Hours: 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays

- Lefty’s Cafe museum deli hours: 11 a.m.-3 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays

- Admission: Adults $8, students & seniors $5, members and children under five free

Sara Lee Silberman

What a wealth of scholarship and ideas in this piece! My compliments! Sorry I cannot see the show. I love Pander’s pieces. And, of course, Rembrandt’s….