Yesterday was May 1st, International Labor Day, the traditional day for honoring workers and workers’ movements internationally. It originated, interestingly enough, out of the labor union movement in the U.S. in the late 1800s, calling for an 8 hour work day. Would’t you know it, the day is not officially recognized in this country today, since any sort of emboldening international solidarity is resisted.

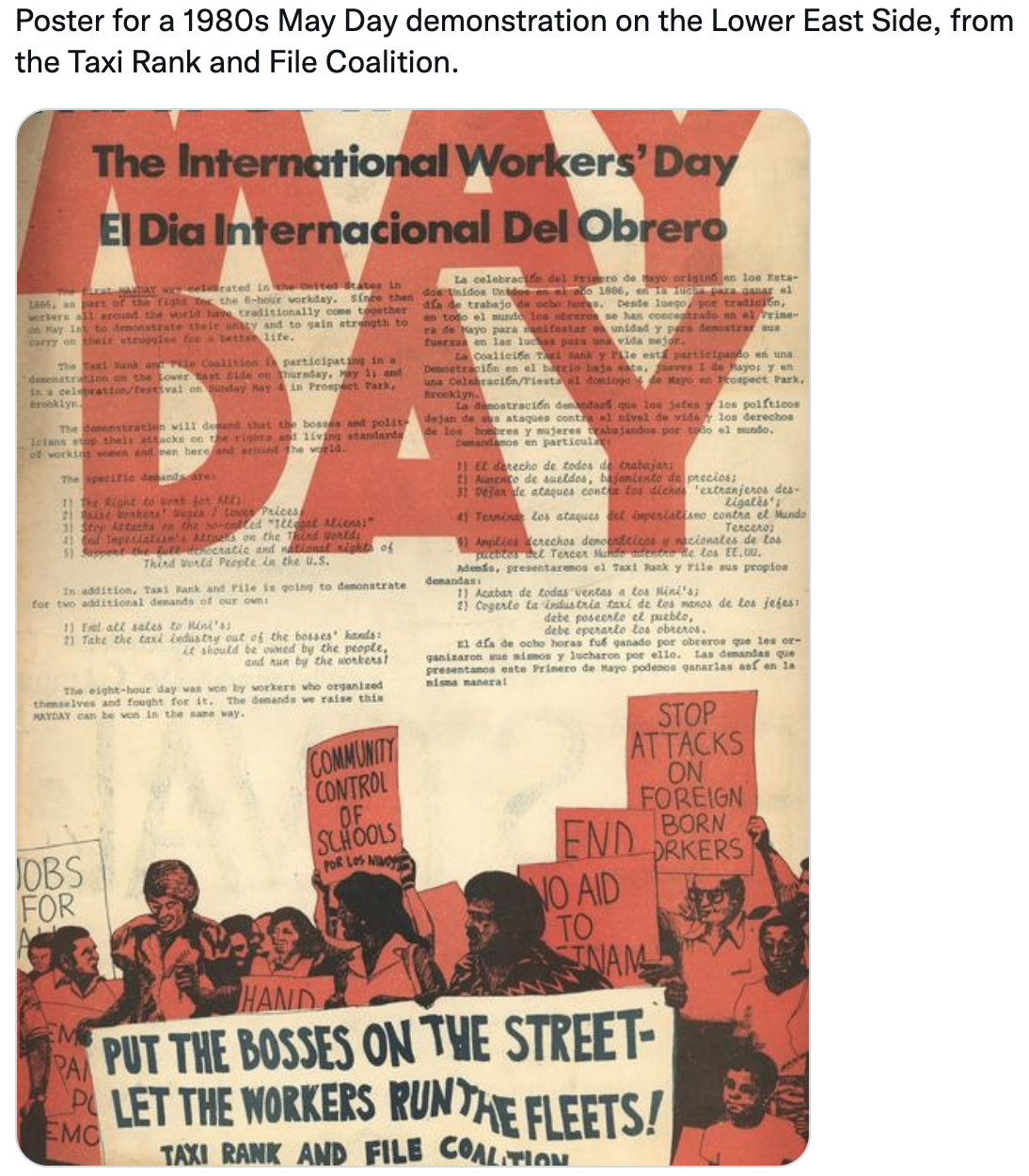

(In honor of May 1st, today’s images are of posters around the world, found in postings by @Jacobin.)

In any case, it is a day that sees protest marches around the world, not all related to labor issues but more generally questioning capitalist rules or political developments (in France, for example both the left and the extreme right were protesting yesterday against Macron’s victory, in Germany large blocs of people protested against housing prices and policies and in favor of feminist politics.) These protests often see large police contingents posted to intervene if violence breaks out, to arrest those perceived to break laws and to protect interests of the state. In Berlin alone, 6000 police officers were posted across the weekend.

When those arrested are brought to trial, the police are called on to testify as eyewitnesses. This brings me to the actual focus of today’s blog, the many myths surrounding the evidence provided by police in general criminal proceedings, as described in a paper by psychologists Kathy Pezdek & Dan Reisberg, Psychological Myths about Evidence in the Legal System: How Should Researchers Respond?, to be published in the Journal of Applied Research in Memory & Cognition in June.

The article describes some of the myths that pervade the legal system. I will alert you to the myths that are listed and why it is important that we become aware that they, as it turns out, have no basis in fact. I will not reiterate the scientific literature that shows how these myths are debunked, which is the core of the scientific paper, but would go beyond the scope of a blog. (Preprints for the whole article can be requested here: Kathy.Pezdek@cgu.edu, or here: reisberg@reed.edu.)

Myth #1: Officers are More Accurate Eyewitnesses than Civilians

Judges, jurors, and many others believe that law enforcement personnel are more credible than other witnesses when they testify in court and, moreover, that officers are more accurate eyewitnesses than civilians. A related claim is that identification evidence provided by police officers is more reliable than identification evidence provided by civilians, and thus the safeguards generally required when civilians are asked to make an identification – safeguards that include proper instructions before the identification, a properly constructed lineup, and so on, are not needed for police officers.

The reality: Police officers have no advantage as eyewitnesses in identifying the perpetrator. Some studies even suggest they are at a disadvantage.

Myth #2: High Stress Improves the Accuracy of Memory

Many people buy into the belief that stressful events are better remembered – and, in fact, are remembered accurately, completely, and with little or no forgetting as time goes by. Ain’t so, and that goes for police officers as well. If anything, high stress impairs memory, rather than enhances it. In addition, memory for stressful events, just like memory overall, can be influenced (and distorted) by post-event misinformation, so holds no special status.

In other words, then: officers suffer perceptual and memory distortions when under stress, just as civilians do.

Myth #3: A Sleep Cycle after a Use-of-force Incident Improves Memory

There are many policy proposals supported by state legislatures and police unions that there should be a “cooling off period” after the use of force before questioning the involved officer, periods trending in length from 72 hours to 10 days. Often this proposal is part of a policy termed the “police officers’ bill of rights.” The claim is that this delay will improve memory, in addition to helping the officer regain composure and get some rest. This stands in conflict with what the evidence shows: delayed reporting is inferior to reporting immediately after an event. Memory fades, folks.

In addition, delay in reporting creates a risk that the officer (or any other witness) will encounter information that can merge with their original memory, undermining memory accuracy. Confusing the source from which you gained knowledge is also enhanced with he passage of time. Even if one did not eye these proposals suspiciously as a tool for the involved officers to get their act together and prepare and coordinate testimony, the suggested delay will hurt not help the finders of fact and the legal proceedings in general.

Myth #4: Double-Blind Lineups are Unnecessary

For photographic lineups, a double-blind procedure is one in which the lineup is administered by someone not involved in the investigation, so that neither the administrator nor the witness is told which photo shows the police suspect. With this procedure in place, the witness makes a selection guided only (one hopes) by the witness’s recollection of the actual culprit’s appearance, and not due to some (involuntary or voluntary) cues or hints by the administrator, and this does diminish bias in identification procedures. Despite their protestations, police officers are not immune to the effects of non-blind lineups. In other words, they, too, should be asked to identify culprits using the double-blind procedure.

Myth #5: Viewing BWC Footage Does Not Contaminate Officers’ Memory

After using force, law enforcement officers are asked to write a report, describing the episode. In many jurisdictions, police insist that they should write the report only after reviewing their body worn camera videos. Any suggestion to the contrary has been strongly rejected by police organizations. This refusal ignores the data that show how memory accuracy is contaminated by seeing the video. It provides the officers with actually-not-remembered information, and this information is simply absorbed into their eventual “memory” report – exactly the pattern expected based on decades of research on post-event suggestion.

Myth #6: Police Officers Can Accurately Detect Deception

There is a widespread notion that police officers are trained to detect liars and are better than your average civilian at doing so. Just for the record: we are all pretty lousy at detecting deception: on average not much better than tossing a coin. Law enforcement officers are not much better in their performance – but do assume that they are. Their confidence levels in their ability to detect lies stand in little correlation to their actual abilities. Training or experience do little to improve these skills, but they seem to feed into false assurance about skill levels.

Why does all this matter?

For one, if legal decisions are made based on false assumptions (evidence given by police witnesses is superior, thus can be trusted over diverging evidence, for example,) we are in trouble. Educating judges, attorneys, jurors and the police themselves seems important to avoid false conclusions that decide people’s fate. These myths are also often reflected in policy documents that govern both law enforcement and legal procedures. It seems important to debunk the mistaken beliefs of policy makers as well, given how consequential these myths are.

And here is some traditional May day music.

Here is Toscanini!

A song from 1931 by Florence Reece…

Working in a coal mine….

Here’s 16 tons….

There’s Power in a Union…

And the working man’s blues…

Philip B Bowser

Spectacular and important! Thank you for this!

Maybe I mentioned this before, but in my 20s the cops took me to the station to identify two perps. Looking through the glass, I could immediately tell these were not the folks I saw, and said so. They kept throwing at me all of those myths you mentioned in your blog, trying to get me to change my mind. Said it was my civic duty to put those two behind bars. Expressed disappointment in me. It seemed to be never-ending, so I tried “am I free to go?” and that worked.

The two I saw were kdg-1st grade sized children, and I lowered them off equipment in the yard of the street department shop, and told them to scram. The ones shown to me were high-school aged or older. I could have made the identification blind-folded, by trying to lift them.

Renate Funk

You may want to check out the Frida Kahlo exhibition at the Portland Art Museum. Don’t go on the weekend, though. There are a lot of small photographs that you need to get close to to see.

Susan Wladaver Morgan

But what about “Union Maid”? Another favorite of mine is from a Union show put on by ILGWU, of which my grandfather was a proud member, called Pins and Needles. The song is called, “It’s Better with a Union Man.”