Art On the Road: Surrealism and Subversion at The Getty.

· The work of William Blake/Photography by Arthur Tress ·

O for a voice like thunder, and a tongue

To drown the throat of war! When the senses

Are shaken, and the soul is driven to madness,

Who can stand? When the souls of the oppressèd

Fight in the troubled air that rages, who can stand?

When the whirlwind of fury comes from the

Throne of God, when the frowns of his countenance

Drive the nations together, who can stand?

When Sin claps his broad wings over the battle,

And sails rejoicing in the flood of Death;

When souls are torn to everlasting fire,

And fiends of Hell rejoice upon the slain,

O who can stand? O who hath causèd this?

O who can answer at the throne of God?

The Kings and Nobles of the Land have done it!

Hear it not, Heaven, thy Ministers have done it!

-by William Blake (1757 – 1827) Prologue, Intended for a dramatic piece of King Edward the Fourth (1796)

***

War was on my mind when I climbed up the footpath to the museum on the hill. War has been on my mind intermittently since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but now, with hell as well descending on the Middle East, it’s become a permanent renter in my head. The piece of art that brought the horrors of war most indelibly home to me this year was Jorge Tacla‘s Sign of Abandonment/Señal de abandono 34, a panoramic view of collective suffering, exhibited in the context of Portland’s Converge 45 biennial and reviewed here.

Jorge Tacla Sign of Abandonment/Señal de abandono 34, (2018) Oil and cold wax on canvas Courtesy of Cristin Tierney Gallery

A frontal view of city blocks reduced to rubble evoked the real-life catastrophe of the siege of the Syrian city of Homs from a decade ago. Tacla’s monumental painting bears witness to the past, but might as well have been prophecy, since the current images out of Gaza, bombed to shreds by the IDF, can be seamlessly superimposed on his painting, with no visual gaps.

I was on my way to explore the work of a different artist also concerned with the futility of war and the destructive power of oppression by state and religious actors. It turned out to be a remarkable exhibition, an international loan on view at the Getty. Organized by the Getty and the Tate, where the work was first shown in 2019, William Blake: Visionary presents several hundreds of his prints, paintings and watercolors, with museum signage that focuses on the diverse roles he assumed – printmaker, inventor, independent artist, poet – and the historical context of life in 18th century England.

The Getty courtyards sport larger-than-life images and banners of Blake’s imagery. The stairs approaching the exhibition halls are covered with what I believe to be a partial of Blake’s frontispiece The Ancient of Days, from ‘Europe’.

Sort of strange to stomp on work before you’ve even encountered it. Then again, the staircase looks pretty spectacular, and spectacle was likely the goal, certainly the result for some of the staging and lighting of the exhibition, in ways that struck me as a misshapen approach. The entrance to the show is painted and lit in deep glowing reds, visions of hell, fortified later by huge posters of some of the mythological figures that populate Blake’s work. It is attention grabbing, for sure, but attention should be on the fact that most of Blake’s work was done in small format and used tempera paints or watercolors, a softness he preferred to oil painting. More importantly, for Blake it was always about the dichotomy of good and evil, heaven and hell, trial and deliverance – so why augment the infernal side of the pair, if not for its more spectacular nature?

Minor quibble. Seeing so many of the prints and paintings in their original renditions, helpfully guided by introductory overviews of the different aspects of his work and artistic development, was just breathtaking. If I lived in L.A. I would surely return multiple times to take all of it in in more concentrated fashion. There is so much to process, beginning with the biography of an artist who lived in relative obscurity, mostly as a printmaker engraving other people’s designs, or executing his own for commissions that were topically constrained by the wishes of his patrons.

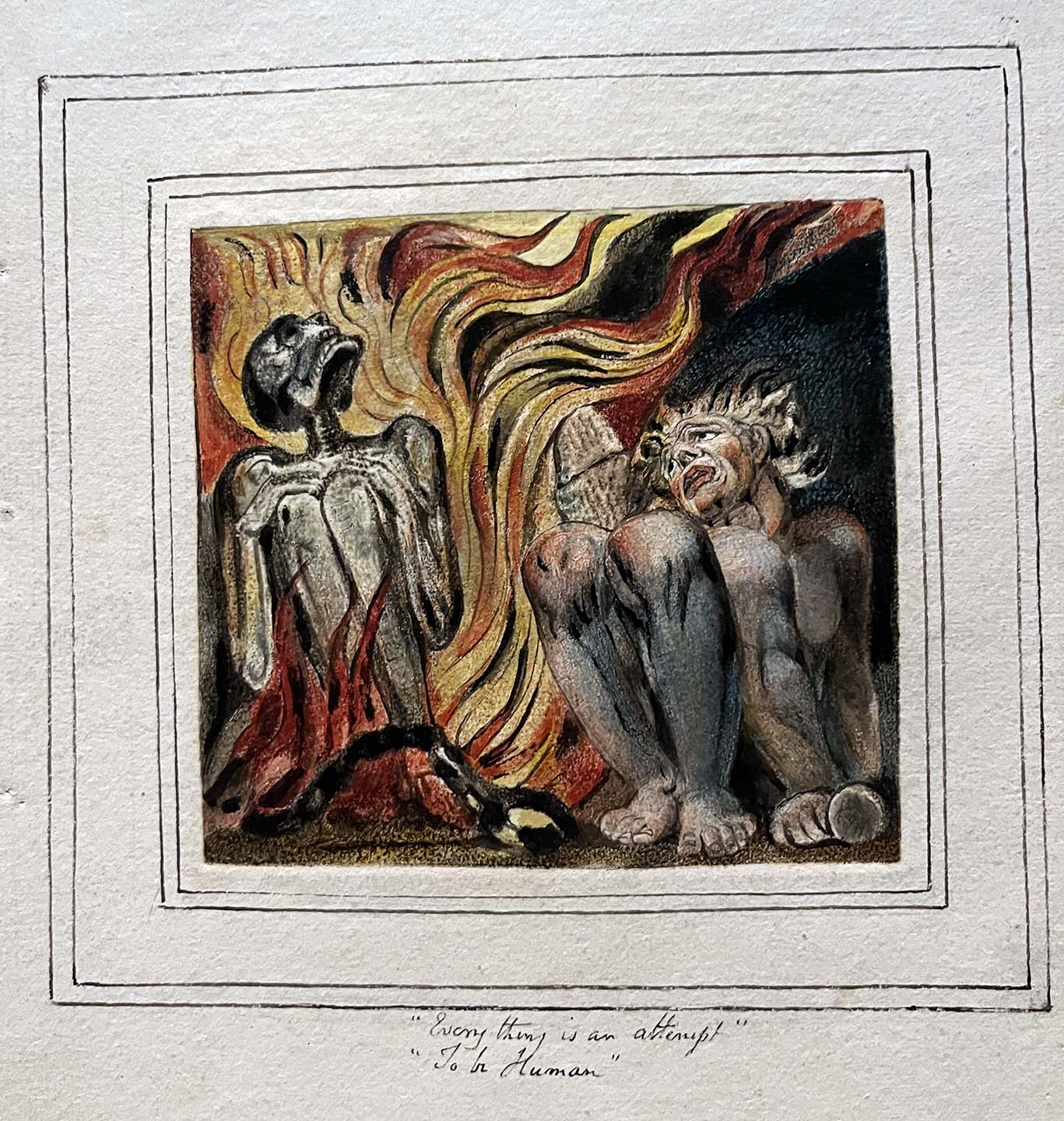

William Blake Plate from The Book of Urizen (1794) “I sought pleasure and found pain.” “Unutterable.”

Only later in life found the son of a haberdasher sufficient financial and artistic support to eke out a living producing his own books, using relief etching, a technique he invented. Everything but his images and words, written backwards, was corroded from the plate, the individual volumes later hand colored, differently for each copy.

He had one solo exhibition of his work in 1809 which failed miserably, not a piece sold, his exhibits derided as those of a “madman.” Even though contemporary romanticism focussed on individualism as well as historical themes, Blake’s visions of either struck the critics as “the wild effusions of a distempered brain.” In some way, his angelic creatures, ancients and monsters paved the way for the symbolist movement, heralded in Jean Moréas’ The Symbolist Manifesto which called for personal visions and a return to mythology in 1886, about a half century after Blake’s death. (I can only dream up an encounter, had he be been born later, between Blake and the daring symbolist Félicien Rops, recognizing each other’s vision for uninhibited love.)

William Blake (Clockwise from top) Nebuchadnezzar (1795-1805) – The Blasphemer (1800) – The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy, Hecate, (1795) Satan Exulting over Eve (1795)

In much of Blake’s work, there is more to both images and poetry than strikes the eye at first glance. His “personal visions” of monsters and mythological creatures were not just the results of an extraordinary imagination. They were a means to criticize the extant political forces in subversive ways, since direct criticism might have cost him his freedom or even life. These figures were creations that aimed squarely at the establishment and its lust for power and/or war. Blake was influenced by and greatly hopeful for the American and French Revolutions. He championed equality, the fight against oppression, was a radical abolitionist and longed for a world no longer ruled by clerics and monarchs.

William Blake Illustrations from the Book of Job (1823)

It is is weirdly contradictory, that he pursued the goals of enlightenment while being strongly against what it stood for: the rule of reason. The First Book of Urizen (1794) (a word he created that implies “your reason” – or “horizon,) if you say it out loud) challenges us to leave the rational behind, and devote ourselves to that more fluid part of our minds, the imagination. And if you look at his passionate strong argument in his poem Marriage of Heaven and Hell, to renounce traditional dichotomies, you wonder why he continued to dichotomize between creativity and reason. (Dreaming up another encounter: Blake meets Martha C. Nussbaum, contemporary philosopher and author of Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotion. Fascinating debate would ensue, you’d think? She argues persuasively that you cannot simply separate emotion from cognition, intuition from reason.)

William Blake Plate from Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion. (1804 to about 1820)

I had written about Marriage of Heaven and Hell and what it implied during the 2021 Jewish High Holidays, a time of contemplation and repentance.

“Blake insists that our existence depends on a combination of forces that move us forward (the marriage of the title.) It might be in the interest of those in power wanting to retain the status quo, to designate us into “Team Good” and “Team Evil,” but for progress to happen we have to acknowledge that we are “Team Human,” as someone cleverly said.

Being human is not either/or, all good or all vile. We are complex enough to accommodate impulses from all directions, to heed some more than others, or do so in different contexts or different times. We might be the just (wo)man at times, or the sneaking, snaky villain at others, going from meek to enraged or in reverse. Change, both in the personal and the political realm, depends on it. Change, in the New Year, will depend on embracing all of what makes us human, and not waste energy to isolate bits and pieces at the expense of others. Intellect and sensuality, rationality and emotionality, acquiescence and rebelliousness can and must coexist.“

William Blake Plate from The First Book of Urizen Fearless though in pain I travel on (1794)

The concepts came back to me when thinking through issues now impacting the world since the horrors of October 7th and the ensuing retaliatory actions. Evermore tempted to designate “team evil” and “team good” in times of contention, the notion of a shared humanity is destroyed by the force of emotions elicited by war: hatred, revenge, religious fervor, lust for power and the economic gains associated therewith. One plate of Blake’s work encapsulates the mechanisms and degree of suffering to prophetic perfection: an engraving of the statue of Laocoön with a torrent of phrases surrounding the image. The most notable aphorism at the base of the image says:

“Art Degraded Imagination Denied War Governed the Nations.”

The priest of yore dared to call out the the function of the Trojan Horse, “some trick of war,” which infuriated the Goddess Pallas Athena. She sent out two serpents who killed the priest’s two young sons in front of him, and silenced him as well. Troy was sacked, with thousands slain. Laocoön himself, a priest for the party of dominion, was in a way participant to the war, which goes to show that all can be destroyed who partake, even if they try to do the right thing. Had his imagination, his vision, been heeded, things might have ended differently. Note also the disproportionality of Athena’s retribution – the life of children taken as revenge for a disturbance of her plans.

William Blake Plates from Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion. (1804 to about 1820)

I find Blake’s lines cited at the beginning of today’s review more realistically geared towards the causes for so much horror in the world, having less to do with neglect of art and imagination, and more to do with tribalism, claiming superior rights and power:

The Kings and Nobles of the Land have done it!

Hear it not, Heaven, thy Ministers have done it!

Plus ça change plus c’est la même chose – the artist is strikingly relevant at this very moment.

William Blake Plate from The First Book of Urizen Vegetating in a Pool of Blood. (1794)

—

There is familiar fare in the exhibition as well, for many of us, I presume.

William Blake Songs of Experience – The Tyger (1825)

Then there was work new to me. One of my favorite series, if only because it brings some light into all the infernal gloom in his work and in my head, were some selected illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, begun in 1824, which show Blake at the height of his power, late in life. And Dante’s story ends with redemption, if you recall.

William Blake Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy (1824-7)

This is work that is visually deeply modern. Seen out of context wouldn’t you buy the notion that this watercolor is potentially by Matisse or Chagall?

William Blake Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy – The Ascent of the Mountain of Purgatory (1824-7)

What has me in awe of this artist is not that he was ahead of his time, though, in visual style or thought. Rather, he distilled, in image and word, the essence of the problems that need solving, across the entire span of humanity’s existence: how can freedom and peaceful coexistence be guaranteed for all, in a world competing for resources and serving diverging ideologies?

Slaughtered children are not the answer.

William Blake Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy – The Pit of Disease – the Falsifiers. (1824-7)

***

“Lyrical, dramatic, fantastic, macabre, mystical, revelatory.”

These are words I picked up from the museum signage. Not for Blake, it turns out, although they would fit to perfection. They addressed imagery of another exhibition that is currently on view at the Getty Center, Arthur Tress: Rambles, Dreams and Shadows.

The descriptors above were not the only parallel. Just like Blake, Tress depicts not what his eyes perceive, but what his mind creates, except that he does it with a camera instead of a brush or an engraving tool, in his series The Dream Collector.

Arthur Tress Boy in TV Set, Boston, MA (1972)

Arthur Tress (Clockwise from Left):Boy with Duck Deco, Passaic, NJ (1969)- irl with Dunce Camp, P.S.3, NY, NY (1972) – young Boy and Hooded Figure, Ny, NY (1971) – Girl in White Dress, Cape May, NJ (1971)

At a time where photography was determined to document the reality of American life, though street photography in particular, Tress started to stage photographs with the help of young participants. He arranged scenarios that captured our attention with their surrealistic character, again not unlike Blake, but also concisely chronicled the environmental and social conditions his young co-creators faced. During the decade of 1968-1978, the photographer integrated his ideas about dreams, fantasy and nightmares into the traditional documentary approach, with haunting imagery as a result. At times, it has ben described as social surrealism.

Arthur Tress Falling Dream, Coney Island, NY (1972) – Flying Dream, Queens, NY (1971)

The work is enigmatic, and was certainly cutting-edge at a time when sociological realism ruled photography. Worth a visit in parallel to the William Blake exhibition, to remind us that unbridled creativity can happen in all mediums, and menacing fears are not confined to the imagination of the giants on whose shoulders we stand.

If only the fears could be contained in nightly dreams and not reflect the days’ reality of war.

Arthur Tress Boy in Flood Dream, Ocean City, Maryland (1971)

________________

William Blake: Visionary

October 17, 2023–January 14, 2024, GETTY CENTER

Arthur Tress

Rambles, Dreams, and Shadows

October 31, 2023–February 18, 2024, GETTY CENTER

Getty Center

1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90049

Hours

Tuesday–Friday, Sunday 10am–5:30pm, Saturday 10am–8pm, MondayClosed