“There is in the universe neither center nor circumference.” – Giordano Bruno, On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, 1584.

JUNE 9th, 2023 was one of my lucky days. After a week that saw so many bleak events across the world, I found myself surrounded by beauty, and urgent reminders that the universe is larger than our tiny selves.

Lucky, because I was alerted to the photographic exhibition by coincidence: an instagram post by the preeminent print studio in town, Pushdot, saying that one of their clients had a show that very day – and only that day – in my neighborhood.

Lucky, because the artist is a friend and colleague who spontaneously agreed to meet me at the venue before official opening, so I could avoid inside crowds.

Lucky, because I got a one-on-one tutorial about how the stunning abstracts on display were created.

From the top: a number of artists and organizations came together to offer a music and art festival at Lewis & Clark College last Friday. EARTH’S PROTECTION, hosted by Resonance Ensemble and featuring special guests, included a drumming and dance demonstration by the Nez Perce performing ensemble Four Directions, information booths from Portland Audubon, and Songs for Celilo by composer Nancy Ives and Poet Ed Edmo – their tribute to the human, cultural, and planetary costs of the 1957 flooding of Celilo Falls which was premiered at The Reser last year and reviewed in OregonArtswatch. At the center of the evening concert was the Oregon premiere of Sarah Kirkland Snider’s Mass for the Endangered, with projections by Joe Cantrell and Deborah Johnson. What would I have given to hear the music – but again, I can still not be inside with lots of people.

Joe Cantrell Jingle Dance (2023)

However, I could visit the art exhibition accompanying the proceedings: Joe Cantrell‘s We are ALL ONE.

Cantrell was born into the Cherokee nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, over 70 years ago. He served two tours with the Navy in Vietnam, including as a diving officer in the Mekong Delta, and then worked as a photojournalist in SouthEast Asia until 1986. The pronounced mildness in his eyes and the gentleness of his demeanor belie the traumatizing experiences that defined his younger years. During his decades in Oregon, he taught both, at the Pacific Northwest College of Art and the Oregon College of Art and Craft. He is a photographer of note in so many ways, providing portraiture and event documentation for art organizations around town, but also specializing in Fine Art photography with his exploration of flora and rocks and fossils.

Joe Cantrell

We connected a few years ago over a shared preoccupation with the ways external or internal components of our experience merge to affect our work. Joe has better ways than I to define the process, ways that are rooted in and amplified by his heritage as a Cherokee, focussed on the interconnection of all things, embracing a multitude of perspectives, be it science, philosophy, history, and, of course, art. His work shines not only due to this conceptual grounding, though. He is ever curious to explore and apply technological advancements that allow him to create work that is unusual, and, yes, I repeat myself, stunningly beautiful.

Joe Cantrell Coming Home (2023)

The images on display were photographs of fossils and polished rocks, macro photography that goes deep inside the object to the very last level that can be captured in focus, then the next one, and the next one, until the surface is reached. A new computerized technology then stitches all of these individual takes together until the full image is constituted, abstractions and configurations resulting from stacking of sometimes more than 70 individual photographs of a single layered object. The color is natural and not photoshopped and appears during post-stitching.

Joe Cantrell Peace (2023)

One of the objects for macro exploration.

Clockwise from left: Joe Cantrell Reef (2023), Oregon Wood (2023,) Fourth Dimension (2023)

Joe Cantrell Stasis (2023)

What emerges are worlds of swirling waves, clouds, geometric patterns capturing all the movement of the elements one can imagine going into the formation of these rocks, the ice, the storms, the droughts, the millennia of relentlessly pounding external forces. A mirror image of the photographs we now receive from space through incredible technological advances, of worlds, of universes, here all captured in a single fossil or a fragment of a rock, for us to behold, whether in our hands – the object itself -, our eyes – the art that emerged from the vision, skill, and patience of the artist -, or our minds – the concept that relations can be captured multi-directionally, as long as we give up the notion that we are the center of the world.

Joe Cantrell Barton (2023)

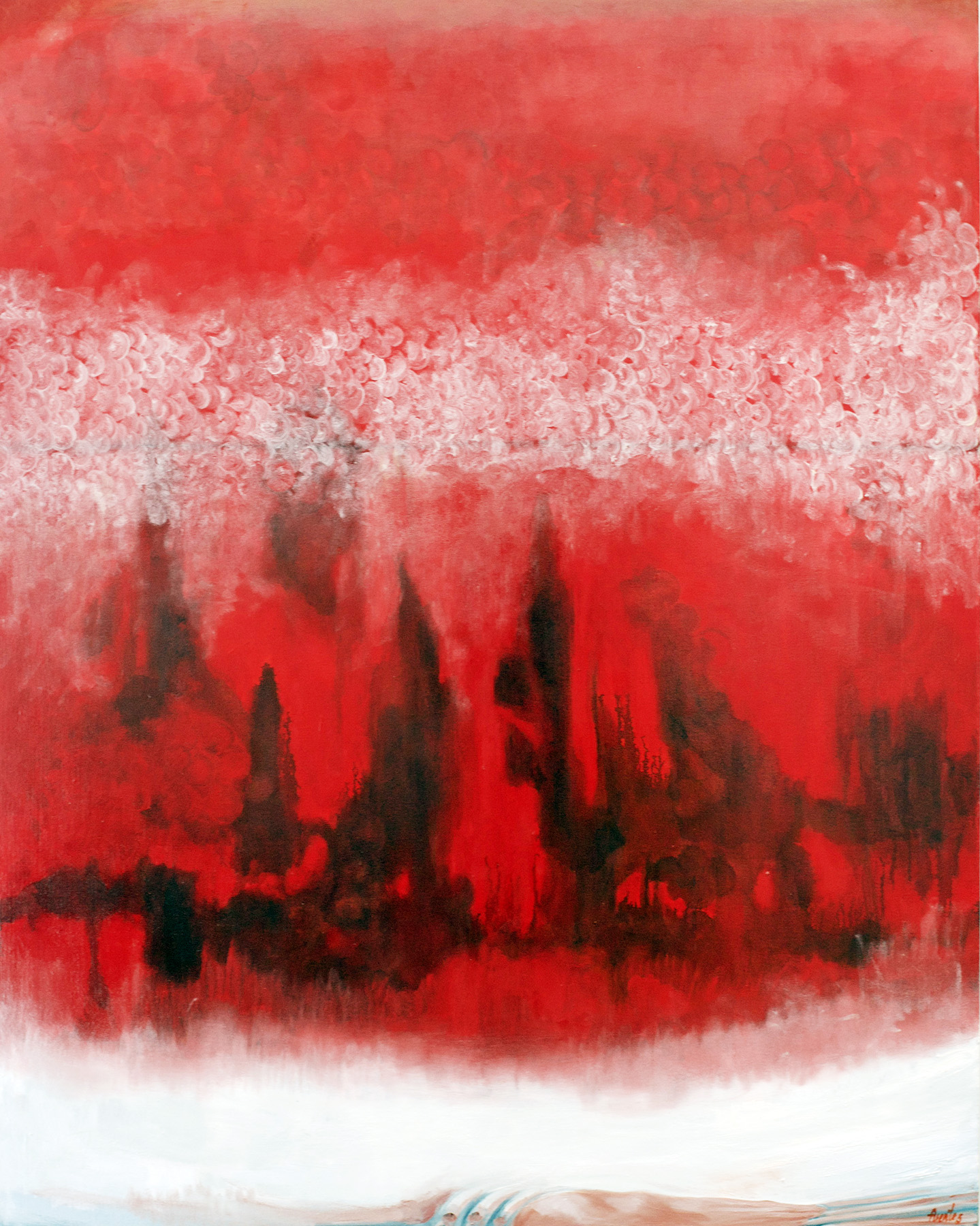

Joe Cantrell The Gates of Hades (Welcome!) (2023)

Joe Cantrell Fractal Playpen (2023)

The stones include Oco, opals, trilobite, and different kinds of agate.

Sometimes natural forms have been preserved in amber or are fossilized in other ways, like these dinosaur feathers and the insect.

Joe Cantrell Dinosaur Feather & Amber – 320 million years old, give or take (2023,) Fungus Gnat (2023)

Joe Cantrell Ammonite (2023)

Again, Giordano Bruno, 16th century scientist, philosopher, heretic:

“There is no top or bottom, no absolute positioning in space. There are only positions that are relative to the others. There is an incessant change in the relative positions throughout the universe and the observer is always at the centre.” On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, 1584.

Let me juxtapose that with Joe’s perspective, in his own words:

“Yet in a universal perspective (whether we are aware or not, the one in which we all exist) our entire planet seems microscopic, and we, with all our “achievements,” and superstitions and egos, an insignificant, self-destructive nothing. BUT, we are part of All That! See!

Resonance Ensemble’s call to action for this festival was dedicated to protecting the earth, learning to be stewards rather than clinging to ownership with the rights to limitless extraction. Joe’s work addressed those issues with a message derived from earth materials themselves: Let us center ourselves a bit less and join the whole a bit more, acknowledging shared origins. The profusion of color, form, movement and subtlety inside all of these photographs will help to do just that, reminding us of one of the ultimate building blocks of the universe we inhabit: cosmic dust linking us all.

Joe Cantrell Lillian (2023)

Music today is a 2020 version of Sarah Kirkland Snyder’s Mass for the Endangered. It is a celebration of, and an elegy for, the natural world—animals, plants, insects, the planet itself—an appeal for greater awareness, urgency, and action. She explains:

“The origin of the Mass is rooted in humanity’s concern for itself, expressed through worship of the divine—which, in the Catholic tradition, is a God in the image of man. Nathaniel and I thought it would be interesting to take the Mass’s musical modes of spiritual contemplation and apply them to concern for non-human life—animals, plants, and the environment. There is an appeal to a higher power—for mercy, forgiveness, and intervention—but that appeal is directed not to God but rather to Nature itself.”

And here is the Agnus Dei from An African-American Requiem by Damien Geter, performed by the Resonance Ensemble some years back.