Songs from the Congo

· Black Artists of Oregon/Africa Fashion at Portland Art Museum ·

““I am black; I am in total fusion with the world, in sympathetic affinity with the earth, losing my id in the heart of the cosmos — and the white man, however intelligent he may be, is incapable of understanding Louis Armstrong or songs from the Congo.”

– Franz Fanon Black Skin White Masks, 1952

Last week I visited Africa Fashion and Black Artists of Oregon at the Portland Art Museum, downstairs and upstairs in the main building, respectively. Downstairs was empty, upstairs was jumping, middle of a weekday, for a show that has been open since September. I started my rounds on top and my eye was immediately caught by a group of young women motionless, except for their heads.

What were they staring at? Bent over, studying, then four heads lifting in unison, looking at each other, then bending again, back and forth, like a silent dance. Once the young women left, I walked over to see for myself and found this:

damali ayo Rent a Negro.com (2003) You can listen to the artist explain the evolution of this work here.

What reaction would an interactive piece like this, riffing on the commodification and objectification of Black labor, elicit in high school students who are most likely not (yet) too familiar with conceptual art? One of the first satirical pieces of internet art, damali ayo‘s Rent-a-Negro is an ingenious take on the system that has progressed from purchasing and owning the Black body to leasing it (although prison labor needs to be considered a form of slavery, if you ask me,) to using token Blacks to satisfy demands for “diversity.” How would it be processed by the Black high-schoolers in contrast to those like me, old White folk? Rage and revulsion by those whose ancestors were subjected to exploitation and oppression, ongoing even? Shame and sorrow by those whose forbears might have wielded the whip and ran the auctions, with patterns of discrimination not a thing of the past?

Julian V.L. Gaines Painfully Positive (2021)

Ray Eaglin Maid in USA (1990)

Fanon’s insight that someone like me will not be able to understand certain forms of art as they would be by those from whom it originates, popped up in my head with urgency. And this leads to one of the elephants in the room that needs to get aired: how does a White woman review exhibitions of Black art with the depth and understanding they deserve, while aware that the racial, potentially distorting, lens cannot be abandoned? It is naive, bordering on ignorant, to assume that art can be seen, understood, felt in some neutral fashion, when our implicit stereotypes guide our interpretations, and when our lack of knowledge specific to the history of a community affects our comprehension.

Tammy Jo Wilson She became the Seed (2021)

Al Goldsby Looking West (ca. 1970)

Furthermore, any reviewer aware of their implicit biases and wishing to be an ally to those who are burdened with historical or ongoing discrimination, will walk on eggshells. You want to avoid harsh criticism, or piling onto stereotypes, or being overly deferential, despite all of that being already a form of unequal treatment, born from awareness of culture constructed around race. You so want to avoid putting your foot in your mouth and appear arrogant.

Or racist.

Thelma Johnson Streat Monster the Whale (1940)

Mark Little Despondent (1991)

Isaka Shamsud- Din Land of the Empire Builder (2019)

I vividly remember a lecture I gave about the psychology of racism on invitation by PAM in the context of a Carrie Mae Weems exhibition over a decade ago. I talked about the Implicit Associations Test – IAT – the psychological measure that confirms how many of us hold stereotypical assumptions associated with racism. It is a test that looks at the strength of associations between concepts and even the most liberal takers have gasped at their scores. Mind you, it does not mean you are a racist; it just tells us that we have all learned associations between concepts that involve stereotypes associated with Blacks. Some in the audience erupted in anger, astute, educated, intelligent docents among them. That could not be true! They fought against racism all their lives! I clearly failed in getting the point across: there is a difference between consciously acting on your stereotypes and unconsciously being affected by them. But even the latter was denied by these well-meaning citizens.

Jason Hill Lion King (2019)

In any case, one can have read brilliant work like Franz Fanon’s about the Black psyche in a White world, racial differences, revolutionary struggle and the effects of colonialism until the cows come home, it will not ease the task of reviewing exhibitions like the one currently on view. Not that that has kept me from doing so, most recently with Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems in Dialogue at the Getty and Red Thread/Green Earth which showed work of several members of the Abioto family at the Patricia Reser Center for the Arts.

But it has made me aware of how much I already censor in my head, how worried I am about the reception of my takes, and the damage they could do, how my approach to work are colored by the political context, something that would not happen if I just walked into any old show of a collection of artists, race unknown.

Ralph Chessé The Black Women Work (1921)

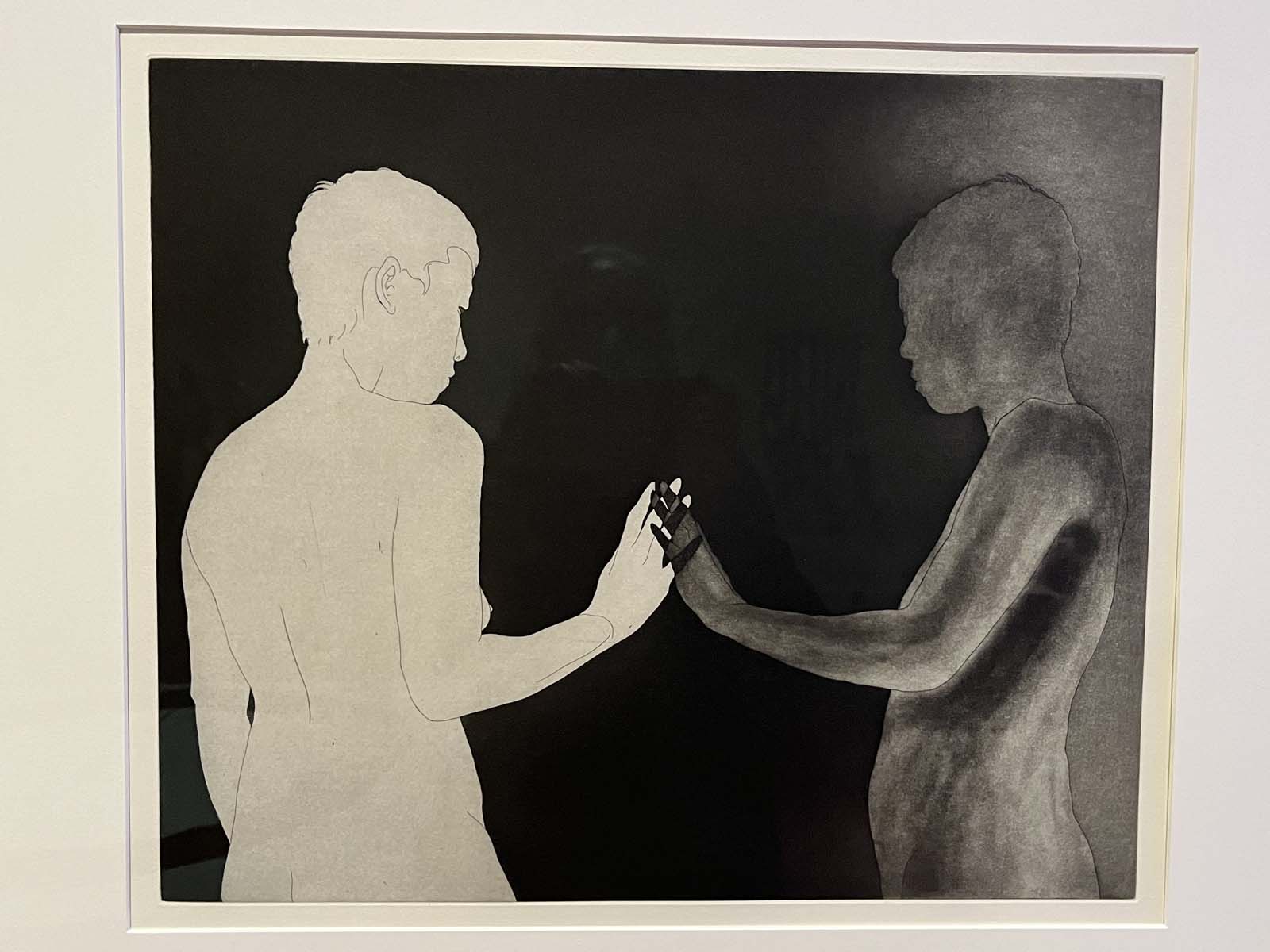

Bobby Fouther Study in Black (2023)

***

The current exhibition was curated by Intisar Abioto after years of research into the spectrum of Black artists in Oregon, some famous, some locally known, some hidden in the embrace of their community. She put together a remarkable show, and her line of thinking as well as the expanse of the art is fully explained in a in-depth review by my ArtsWatch colleague Laurel Reed Pavic, who talked to the curator and listened to her podcasts about the exhibition. (You can listen to the podcasts yourself – they range from general introduction to a number of interviews with individual participating artists.)

My first association to the upstairs show was the contrast to what is exhibited downstairs, African Fashion. Previously shown at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum and the Brooklyn Museum, the latter was hailed as a vital and necessary exhibition by eminent art critics. It felt to me, however, like one of those luxury fruit baskets filled with luscious and exotic goods, wrapped in cellophane with a glittery bow – something that often does not live up to its visual promise when you are actually starting to peel the fruit.

Contrast that with the show upstairs: like a farm-to-table box dropped off at your doorstep, stuffed to the brim, packed to overflowing, with produce you sometimes don’t even recognize, but all locally grown and, most importantly, invariably, truly nourishing.

Katherine Pennington Busstop II (2023)

Latoya Lovely Neon Woman (2019)

Packed is the operative word here, 69 artists and over 200 objects, sorted into categories like “expanse, gathering, collective liberating, inheritance, collective presence, and definitions. The art is competing for space, focus, time and attention, with those limited resources not meeting demand. I assume it was a conscious curatorial decision. If you have, finally, a public space willing to open up to a neglected or even excluded collective of artists (collective in the sense of a shared history rather than a shared goal,) you might as well grab the opportunity and allow every one in the community a shot. This is particularly true when you don’t know what the future holds and which opportunities emerge in times where the racial justice backlash is raising its ugly head ever more prominently. Yet you do early-career artists, no matter how promising, no favor when placing them among the hard hitters.

Henry Frison African Prince (1976-79) with details

Alternatively, the inclusion of so many art works might have been a conscious attempt to demonstrate the diversity that is offered by a community long segregated from traditional art venues, never mind neighborhoods. It might be an attempt to shift what psychologists call the outgroup homogeneity bias, our tendency to assume that attitudes, values, personality traits, and other characteristics are more alike for outgroup members than ingroup members. “They are all the same! Know one, you know them all!” As a result, outgroup members are at risk of being seen as interchangeable or expendable, and they are more likely to be stereotyped. This perception of sameness holds true regardless of whether the outgroup is another race, religion, nationality, and so on.

That bias certainly affects what we expect (particularly, when our expectations are driven by other cognitive biases as well.) Our unconscious expectation of less diversity in the creative expressions of the art were certainly put in doubt with the plethora of work put up by Abioto. In confirmation of the bias – and thus the value of her curatorial decisions – I certainly caught myself regularly looking for a common thread of political statements, however indirect, commenting on the experience of being Black in Oregon, a notoriously racist state.

MOsley WOtta Baba was a Black Sheep (2023)

The history can be found here in detail. Simply put, Oregon had not one but three separate Black exclusion laws anchored in the Oregon Constitution and it took until 2001 to scrap the last bit of discriminatory language from the records.

We are one of the nation’s whitest states, and had at some point the highest Ku Klux Klan membership numbers nationally. Of our 4.2 million Oregon residents only about 6% are Black, and many of these have been displaced within the state over and over again, making room for construction projects and/or gentrification of neighborhoods. Nonetheless, Black leadership and organizations providing support for education, including the arts, are resilient and effective. (A recently updated essay by S. Renee Mitchell provides a thorough introduction to these achievements. Another informative article about Black pioneers can be found here.)

Arvie Smith Strange Fruit (1992) Detail below

Much of the art reflects the history, referencing the pain and injustice of lived as well as inherited experience. But there were also pieces that simply depicted beauty, documented landscape, revered what is. No message necessary or intended. It is a conversation I would love to have about all art, at this moment in time, how our ability and willingness to make art outside the need to bear witness, or instruct, or frighten, or alert to social change needed, is obstructed by multiple internal and external forces – but that has to wait for another time.

Sadé DuBoise Collective Mourn (2023) with detail

For this exhibition there was more art on display than could possibly be processed during a single visit. But all of it was nourishing, even in passing, as I tried to express in my initial description – food for thought, yes, as well as a feast for the eyes.

Natalie Ball Mapping Coyote Black, June 12 and 13, 1987 (2015)

Natalie Ball Mapping Coyote Black , June 12 and 13, 1872 (2015) (Artist new to me, enchanted by the work.)

I felt at times as if I was, if not an invited, surely a tolerated guest at a family reunion – meeting of long lost friends and relatives, happy to run into each other, artists introducing each other. It was a vivid, social experience during a time where I am still socially isolated due to the pandemic, even if I was standing double-masked at the margins, observing so many people truly engaging with art, potentially new to them. Twice (!) I was asked to take photographs of people who had met at the museum by chance and talked to each other in front of this or that piece.

I left the museum more hopeful than after any of the recent shows I’ve been reviewing (and the last year included some real winners!). The vibrancy of the work on the walls and the liveliness, even giddiness of the social interactions of many visiting generations all conveyed a sense of resilience and optimism that somehow rubbed off onto me. I might not get the songs of the Congo, but I do have an inkling, provided by this exhibition, of what local Black art stands for: a community that refuses to let go of history, no matter how painful. A community that believes in a more just tomorrow as well, forever willing to fight for it, no matter how hard that is made by the rest of us. A community standing its ground, with art that reflects that strength.

Ralph Chessé Family Portrait (1944)