Taking stock of the body

· New work by Kate Simmons at the Alexander Gallery at CCC. ·

British artist Helen Chadwick fought much of her life, a life cut short way too early, against society’s demands for idealized female bodies, particularly with advancing age. She was a vanguard in pointing out double-standards for gender-related expectations for femininity, but also in her use of materials that related directly to the body, often in constellations that mixed beauty with repulsive features. She managed to take traditional symbols and distort them in surreal arrangements that tended to shock, some time before shock had become a staple in the arts, now used intentionally. A memorable example is her 1991 back-lit cibachrome photograph of blond hair intertwined with a pig’s intestines.

Helen Chadwick Loop My Loop, (1991) Cibachrome transparency, glass, steel, electrical apparatus

Chadwick popped into my thoughts when I visited Kate Simmons’ current exhibition Landscapes and Surfaces at CCC’s Alexander Gallery, thoughts likely triggered by both the issue of physicality and bodily decline that is the focus of much of the work in the show, and the use of human hair in one of its large pieces.

The exhibition consists of cast plaster sculptures, an assembly of glass cloches filled with melted and cold shocked aluminum, a video and an installation of felted wool and spun human hair. It is blissfully not overcrowded, allowing the separate artworks enough room to breathe. It also, important in the context of teaching at a college, manages to combine works created with diverse techniques, allowing her students who might see this a discussion about processes as well as the artistic impulses behind the art.

Kate Simmons and Sierra St. James Senescence (2023) 2 minute 26 second single channel collaborative experimental video.

A video, Senescence, created by Sierra St. James and Kate Simmons, displays overlaid images of seasonal impressions of nature and an exploration of the artist’s body. Hints of the deterioration starting in mid-life make a point about the cyclical nature of it all. Its poignant and at times disquieting message, was, alas, undermined by music composed specifically for this piece. The music itself was fine, but bore no relation to the content of the images, and, if anything, diluted them with a melodious sentimentality that offset the visuals which were wistful, but never sentimental.

When you enter the gallery your gaze is drawn to two large plaster casts of the artist’s head, one upright, the other in recline, both sprouting thorny rose canes made of bronze, with carved wooden leaves. Given the strange pairing of two representational shapes, the heads and the briars, my immediate association was to Sleeping Beauty, if you remember the Brother Grimm’s fairy tale. Here she is now, fully engulfed by the hedge of thorns surrounding the castle, a violent merger between landscape and body, the latter no longer amenable to princely rescue attempts. Turns out, it was an expression of a more personal symbolism, the affliction with Rosacea, a long-term inflammatory skin condition that causes reddened skin and a rash, usually on the nose and cheeks and often appears out of nowhere in times of stress – middle-age no exception, given that the heat of hot flashes is exacerbating the condition.

Kate Simmons Passage (2023) Cast plaster, cast bronze, carved plywood, epoxy, string and acrylic paint. (with details)

Record of Form, a series of five individual cast plaster forms pulled from the artist’s body, spoke to me more, perhaps due to the fact that no immediate interpretation distracts from the perceiving of the abstract beauty of partial bodily shapes. They could be anything, really. Shell fragments, rock formations, shaped horizons, or the crumbling of arthritic joints, worn down discs, sagging forms – it does not matter. Light and shadow, sharp lines, assembled variations – they all work visually without the need for representation, just testament to something physical having been captured and enshrined, a self contained presence.

Kate Simmons Record of Form (2023) Cast Plaster

Two glass cloches at the other side of the room hold strangely formed accumulations of aluminum that was melted and then poured into cold water in Landscapes and Surfaces. My immediate reaction, as will be the ones of my German readers, was to think back to New Year’s eves when a German custom has you heat up balls of lead or pewter over a candle in a spoon, and then pour the liquid into bowls of water. The resulting shapes are interpreted with the help of party-favor handbooks, predicting your future, not unlike fortune cookies, in the year to come. Simmons’ aluminum configurations were larger, bubblier, and looked more substantial under the cloches, but invited speculation as well. Is it cooled lava, is it an accumulation of cancer cells, is it salmon roe, is it bubbles in a waterfall? Landscape or body imagery were equally applicable, and I just regretted that the word body was not part of the exhibition title, to help with the connections that she framed in her artist statement, the parallels she wishes to draw.

Kate Simmons Landscapes and Surfaces (2023) Glass cloches and aluminum.

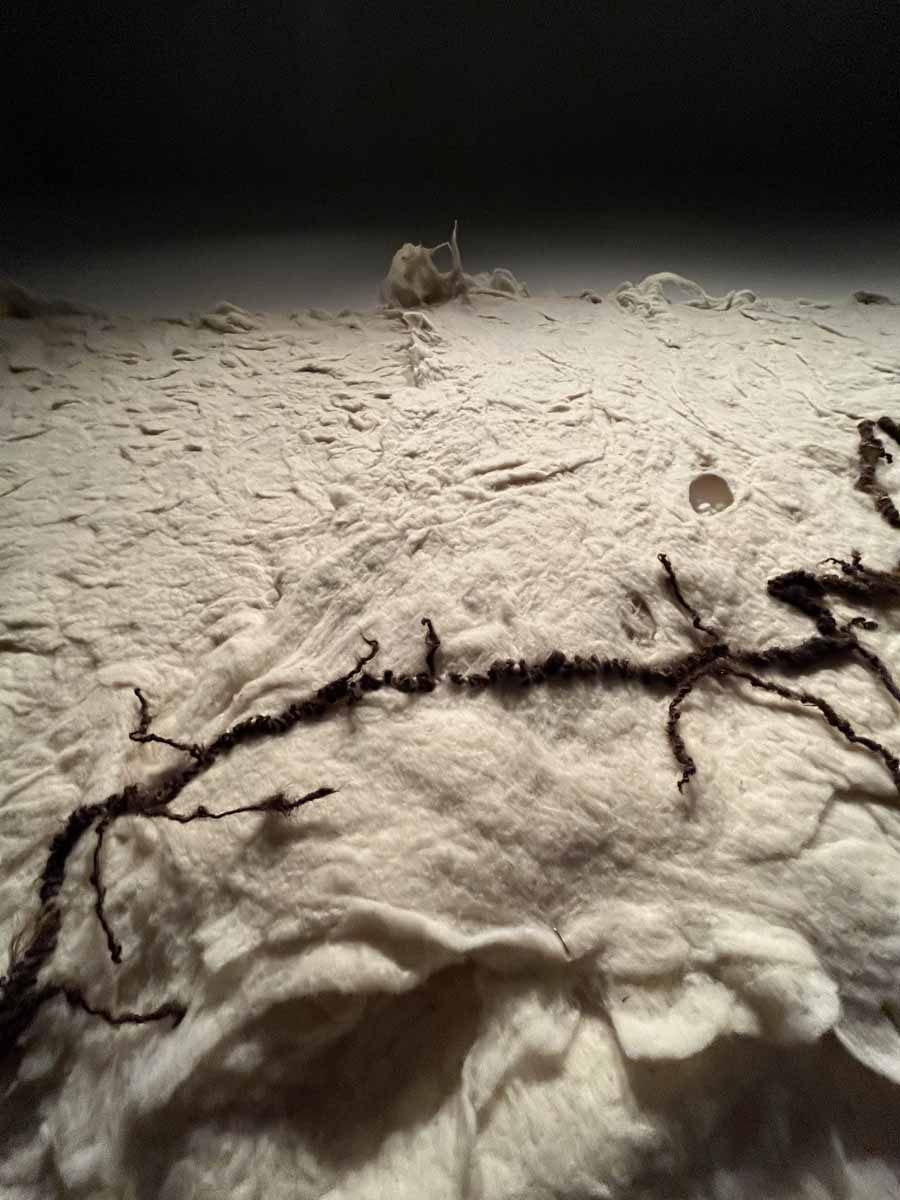

Extended across a wall opposite of the video screen is a large wall hanging comprised of two overlapping, hand-felted wool fleeces with lines of hand spun human hair appliquéd. From her statement:

This work calls attention to macro appearances of landscape topography while juxtaposing micro appearances of human skin or flesh. Mountains and ravines mimic micro textures of wrinkles and crepey qualities of skin as time evolves changing the landscape and the human body. Spun human hair and wool make connections between living creatures. The linear stitched decoration inspires associations to waterways and human vascular systems.

It does all that, but also calls up disquieting associations about the use of hair in very different settings. Which, by the way, is a good thing, even though it made me uncomfortable, because the art invites historical perspectives, and goes beyond the surface, even though surface is the hook it has us hang these thoughts on. Incidentally, I had recently written about the cultural role of hair in the context of artists processing cancer. Here I am back with some thoughts on hair as material used both in everyday settings and artists’ work.

Kate Simmons Erosion (2023) Wool and human hair.

During the Holocaust, concentration camp inmates were shorn of their hair before they were killed in the gas chambers. The hair was was cleaned in an ammoniac solution, dried, and stored in paper bags. It was shipped to German factories for profit, paid by the pound, and used by industry to manufacture ropes, carpets, mattress stuffing, and socks for submarine crews as well as time-bombs. One of the largest German companies for auto parts, Schaeffler, (still dominating the market and being one of the wealthiest families in Germany today) used the hair of 40.000 or more camp inmates to manufacture textiles. Hair has taken on a symbolic role in much of the post-holocaust attempts to work through the horrors of fascism, with Anselm Kiefer and Gideon Gechtman probably being the most familiar names in that arena.

Today, it is reported that China, the largest exporter of human hair in the world, is using both the hair of inmates in Uyghur internment camps and camp labor to provide the world market with natural hair to make wigs and extensions, or other object to the tune of U.S. $1.8 billion in exports to the U.S. alone.

Kate Simmons Erosion (2023) Wool and human hair. Detail

In earlier times, from the Biedermeier period and the Victorian period up to the Second World War, hair was processed as braided and bobbin-laced hair jewelry, into friendship-, mourning- and traditional costume jewelry, as well as into hair locks as keepsakes.

More recently many artists have taken up the significance of hair, sometimes, for example, as a racial marker, in societies where racism prevails. David Hammons used found hair around the same time as Chadwick constructed her golden locks, to alert to aspects of Black culture and our reaction to it, like in this piece that has hair wrapped around wire turn into a semblance of dreadlocks.

Bodily hair is often associated with shame and sexualization. Artists like Palestinian born, London based Mona Hatoum have used (pubic) hair to draw our attention to the way women are forced to accommodate male tastes, but also head hair to the more general issue of human trafficking of young females.

And then there is Gu Wenda, born in Shanghai and now based in NYC, who estimates he has collected the hair of 5 million people for his artworks, installations titled United Nations that are partly shown right now at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA. The artist takes hair and other bodily materials to create similes of the flags representing the member states of the United Nations, reflecting the properties similar to all humans across space delineated by borders. Someone called it a “new form of mysticism and a great utopia of unification.” I would not go there, but the work certainly impresses with how a concept is actually instantiated with unimaginable labor.

Hair as representative of a society bent on categorizing and stifling women, symbol of shame as much as beauty, hair that singles out racial identity or is labeled a uniting factor – where does this leave us with respect to Simmons’ work?

The concept presented in this show lodges around the surfaces and structures of a human body exposed to aging. Parallels drawn to nature’s cycles emphasize the inescapable rhythms of biology. Hair is, of course, a vivid reminder of the elapse of our allotted time: across the years it looses its color, it changes its density and weakens its structure, eventually thinning to the point of no return, with baldness for many the result. The multi-colored strands of hair juxtaposed with the densely matted fleeces, animal hair regularly shorn and growing back in cycles as well, proffers the understanding that we are all part of natural processes. Its visual appearance on the topological hills and valleys of the background is indeed one of veins and arteries (if you think human) or rivulets and rivers, if you’re settled on landscape.

Kate Simmons Erosion (2023) Wool and human hair. Detail

Hair, if not our own, found in unexpected places and configurations, is sometimes associated with disgust. The long hair in the butter dish or the short hair in the sink and shower drain are irritants. Hand spun into the threads, clumped and stretched as we see it in Erosion, it might (or might not) cause similar reactions. I applaud the decision to ignore that possibility and use hair as object, because it is one of the few actual human materials that lend themselves to preservation and bring a piece of us into the world without the need to be represented by something else. If the artist’s ideas circle around us and the world intersecting, exposed to the same pressures, then this is an interesting way to go. The exhibition as a whole serves as a great starting point to think through physical fragility.

Music today is one of the pinnacles of acceptance of aging: the Marschallin in Strauss’ Rosenkavalier sings about the strangeness of time. Still one of my favorite arias of all times.

Kate Simmons Erosion (2023) Wool and human hair. Detail