“Art-making embodies our private struggles with the meaning of life, the relationship between humanity and nature. In a time when our ability to comprehend reality is becoming more and more blurred by our inability to abstract meaning, the visionary abstractionist of natural phenomena represents a way of making art that is inherent and primordial…Through use of organic shapes and a chaotic vocabulary, it is possible to awaken the viewer’s own private demons.” –Frank Kowing (2011)

It all began with a cold call to Linfield University. The family of Native American artist Frank Kowing, one of the first graduates of Linfield’s budding art department in 1966, wondered if they could get help with a treasure trove of work left in a storage unit. Framed, encaustic oil paintings, endless loose canvasses of acrylic abstracts, sculptures made of sticks and found objects, drawings and notebooks were all looking for a home.

Brian Winkenweder, chair of the art department, was hesitant given the fact that the university is not set up to store collections, but upon seeing it all, was hooked. The quality of the work, the link to the institution and the region all deserved an exhibition, with hopes to connect collectors and art lovers to the work for further distribution.

Thea Gahr, artist and curator of the Linfield Gallery, had her hands – and her head – full. Selection is always difficult with a plethora of materials, particularly when works range across domains, span decades, and differ wildly in style.

In her favor, though, were the facts that she excels in taking risks, as I have now seen across several of her curations, had sufficient run-up time to think things through, and commands a space that captures a light seemingly made for or reflected in Kowing’s paintings of Pacific Northwest mountain scapes.

***

—————————————————————————————-

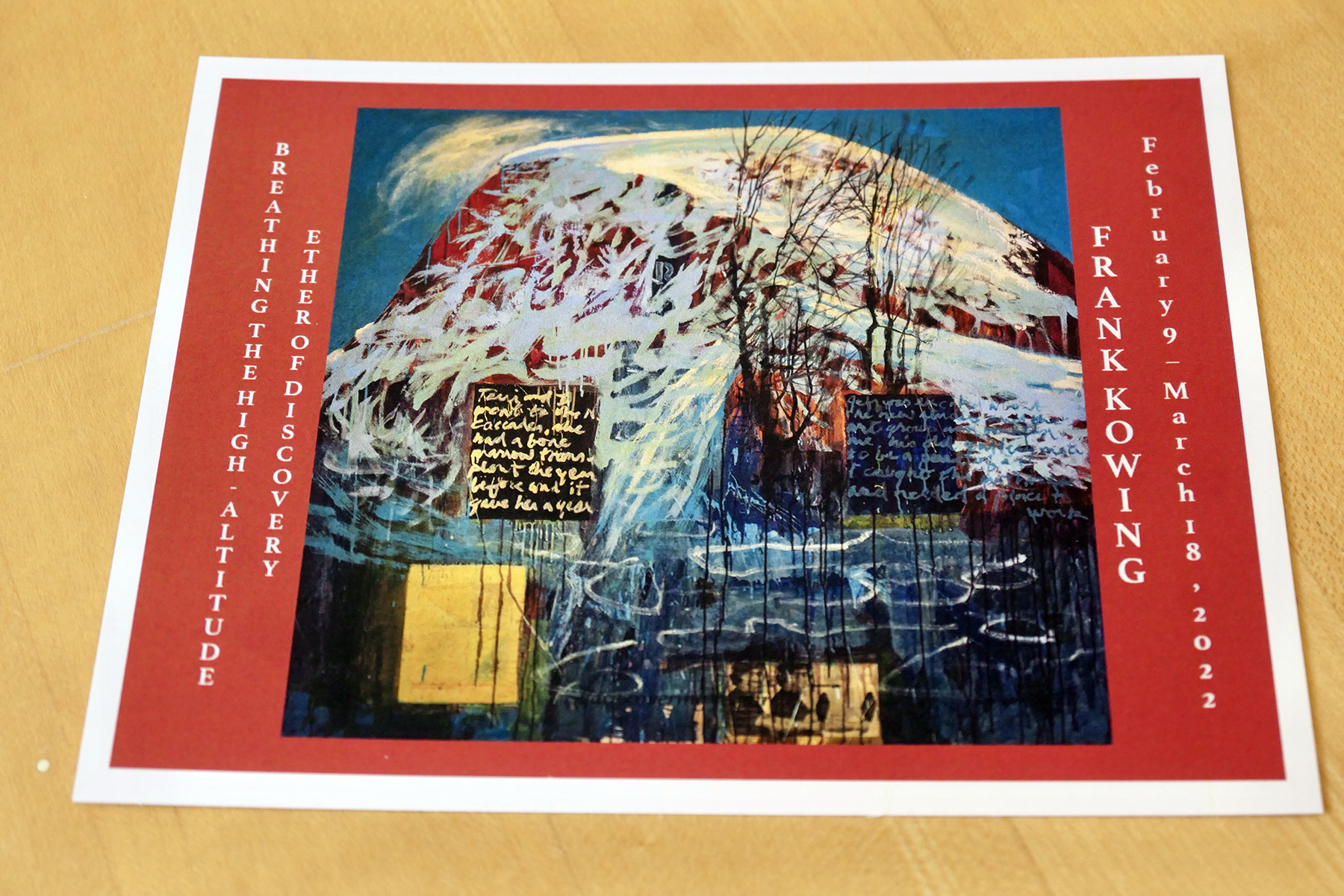

Frank Kowing: Breathing the High-Altitude Ether of Discovery

Exhibition dates: Feb. 9 – Mar. 18, 2022

Opening reception: Wednesday, Feb. 16, 5:30 – 7 p.m.

Experience the paintings, sculptures, and sketchbooks of Frank Kowing Jr. b. April 1,1944 – September 24, 2016.

900 SE Baker Street

McMinnville, Oregon 97128

503-883-2200

—————————————————————————————-

I don’t follow any system. All the laws you can lay down are only so many props to be cast aside when the hour of creation arrives. – Raoul Dufy.

I had entered the empty gallery in the morning, wary of inside visits but determined to get to know what the Linfield folks were raving about and had almost an hour to myself, camera in hand, before meeting with the curator.

Some of the work was truly beautiful, much of it disquieting and all of it forcing you to read beyond seeing, the artist himself disambiguating the visual impressions by including text on practically each and every painted abstract or representation. Or, was the intention to make the work rather more ambiguous? Hard to tell.

Frank Kowing Thought Thing 2009 with excerpts

I did notice an intense push-pull exerted on me. The perception of wholes, of representative forms, of the rhythm and flow of the abstract visual input were constantly battling with the compulsion to decipher what the artist had written for you to read, or included in terms of photographs. The focus narrowed on his written communications, as if he intended to protect the beauty – or the meaning – of his painted visions and landscapes from too close an inspection, any possible intrusion. I couldn’t help thinking that the old adage by the 18th century French philosopher Marmontel, “the arts require witnesses,” had to be extended here to the request that the artist’s life, his struggles, demanded witnessing.

***

Frank Kowing, a member and Elder of the Confederate Tribes of Grand Ronde, was born in McMinville in 1944. (I am grateful to the Kowing family to have made excerpts of an upcoming biography available to me, which allowed me a glimpse of the artist’s life.) He served in the Navy during the Vietnam War, traveling extensively across Asia during his R&R breaks, travel an early passion that would hold true for the rest of his life. Europe was next after his tour ended, where he settled in Amsterdam. He attended the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, an art school that heavily focussed on graphics and design, but probably also provided exposure to the burgeoning neo-expressionist movement that took Europe and then the U.S. by storm during the 70s and 80s, the Austrian Georg Baselitz and Americans Philip Guston and Jeffrey Koons among them.

When funds ran out – a constant struggle throughout a lifetime devoted to making art and forced to making money, in exhausting day jobs as a contractor – Kowing returned to the States, living and working at multiple East Coast locations. He received an MFA from Penn State in the early 70s, joined various art collectives in New York, Pensylvania, D.C. and later Maryland, starting to sell work but never enough to be economically secure, like so many artists. After brief stints in California and a respite year in his beloved Oregon, he joined the Peace Corps in 1985 and spent 2 years teaching children living with developmental disabilities in Tunesia, followed by 6 years as a curator at Meridian House International, a multiservice not-for-profit conference center and museum in D.C.

The frequent shifts in location and occupations where partly the result of structural factors, economic hardship, the opportunities to be part of collectives, a conflicted relationship with established art galleries, the personal anchors of love and friendship found or abandoned.

I also think they were part of an internal restlessness, one driven by an overarching theme in the artist’s life: intense and frequent losses.

He was estranged from his parents, as well as from a son from an early relationship. He lost two beloved wives to death from diseases. He lost his health to a series of grave accidents and subsequent surgeries, the ravages of undiagnosed Lyme disease and increased pain management by self-medicating with alcohol. The zest for life, the passion for nature – mountain climbing in particular, again and again all over the world – the longing for the freedom of high altitudes of any kind, was in increasing tension with the paralysis induced by physical pain and emotional depression.

***

I am writing about this because the work itself draws one into a conversation with the artist’s expressed feelings. When he notates states-of-mind and emotions he communicates with the potential viewer. It is tempting to label him as a confessional painter, just like Sylvia Plath was stereotyped as a confessional writer, given the naked honesty and vulnerable pain and self-reflection associated with her poetry. That would be a mistake, though, in both cases, since the work embodies strategies of communications that are very well aware of the perceiver, and not just centered on self-disclosure, with Kowing implicating the viewer directly in his artist statements.

Frank Kowing – Tree of Life – 2011 with excerpted side-view showing the three dimensional materiality of the work.

“Art is a language, an instrument of knowledge, an instrument of communication.” – Jean Dubuffet

Among the standard models of intentional communication in my own field, psychology, are the so called Gricean assumptions. Grice proposed that we all want to convey meaning, something best achieved if we stick to truthfulness (maxim of Quality) which would be reflected in an artist’s sincerity to communicate or their skill and the selection of an appropriate style and medium in artistic communication. We should also choose the right level of complexity, (maxim of Quantity,) in painting that would be the appropriate levels of visual complexity. Our communication should be non-random (maxim of Relevance,) expressed in the painting’s subject that might included links to our culture, or to personally relevant issues, or historic symbols. Finally, there is the issue of how obscure an expression is, or structurally sound in terms of a painting’s composition (maxim of Manner.) Forget the science speak. Simply put: if you want to get a message across, to be understood, choose your topic wisely and in context, express it without distraction or excess details, and do so in a manner that does not obscure the meaning. Could have said that in the first place, I know.

Frank Kowing self portrait Journal series (Tyger Tyg, Burning Bright) 2011 with excerpts

Kowing basically breaks all of these rules and has us nonetheless completely fascinated with deciphering the meaning he might or might not convey. That is what true art can do!

Here are just some random examples that speak to that point. I had mentioned before that the layout of the representational paintings, the mountain scenes in particular, draw the viewers on the one hand to the beauty of nature, the pristine peaks, yet bind them to the base of the mountains, chained to deciphering the text, loosing the forest for the trees, so to speak. The mountains come in full view only if you stand far away, but the texts draw you close so you can read.

What is the subject and why is it overlaid by riddles?

It is puzzling, but the work soon conjures some strong emotion in the viewer – in my case memories of years spent in a suffocating, cloistered boarding school in the South West of Germany, looking through my classroom windows into the hazy blue of the Odenwald mountains and the Koenigsstuhl, a longing for being out there, away from it all, so intense it almost hurt. It might be different memories for others, but we probably all share that sense of wanting something, someone or somewhere and not having easy access, if any at all.

The level of complexity of Kowing’s work goes overboard, particularly in the abstract expressionist acrylics that are dotted with snippets of text like his beloved Mt. Hood meadows with wildflowers. The words in the oil paintings are also in ambiguous relation to the complex spatial planes depicted in the painting; the photographs and typed pieces of paper are neither clearly foreground nor background, they remind the viewer that the painting is literally a flat surface, immediately contradicted by the three dimensional parts of the paintings created by layers of paint and wax – tactile mementos of ripped open scars or glorious mountain ridges, take your pick.

He has taken the inclusion of signs and text from the legacy of his forbears, collagists like George Braques, to new heights, leaving the viewer at times to struggle.

Un-numbered acrylic

Frank Kowing Acrylic # 84 Date not available

And chaos rules, obscurity is writ large. At least in my head, trying to figure out if Kowing meant the accumulation of fortune cookie predictions or other banal proscriptions scattered across his acrylics seriously, or as a tease, ridiculing our desperate need for unambiguous meaning by serving cultural platitudes cold.

A wonderfully humorous trickster, then, in addition to the deeply serious communicator.

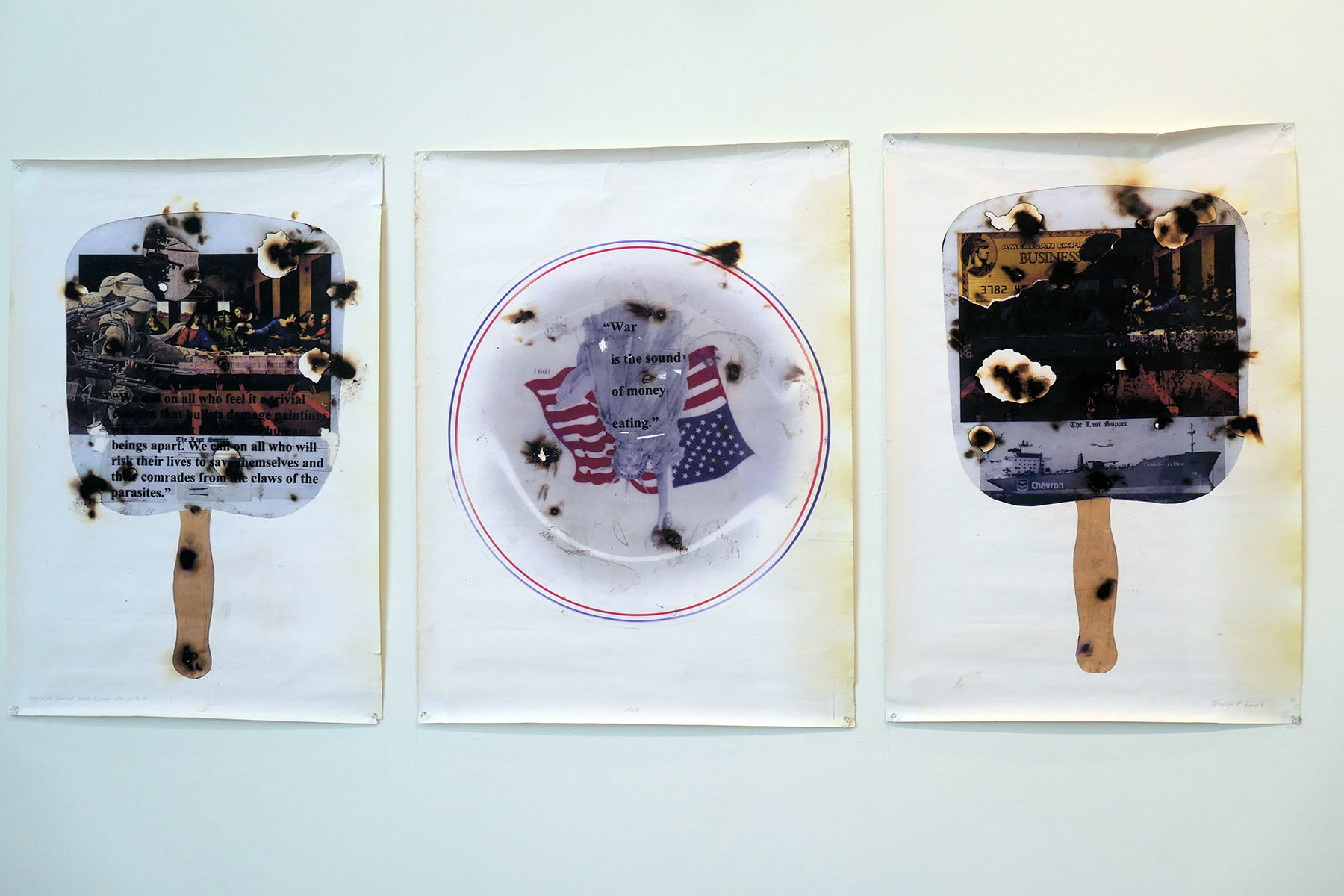

That sense of trickster is reinforced when looking at the possibly invented communication with Edward Kienholz in one of the largest works in the exhibition. Kienholz, famous for his elaborate found-object assemblages which convey a harsh scrutiny of American society, was known to pull major pranks himself, in pursuit of chaos many times over.

Frank Kowing The Sea of Kienholz – excerpts – date unknown

I prefer the emotion that corrects the rule. – Juan Gris

I think Kowing would have liked the photograph below that dimly reflects me in the gallery glass door in front of the exhibition announcement. A faint witness to his art, his wit, his struggles. Moved by learning about this work, his life. And wondering what it is with art that allows communication between an artist and an audience even if they are separated by time, sometimes centuries, by cultural back-ground – Native American Oregonian meet German immigrant – by color or class, with some having the unearned privilege of inclusion in mainstream society, while others don’t.

The true artist knows how to convey basic emotions, cross-culturally shared, I suppose, the woes of longing/not belonging, the irreparable hurts of a past than cannot be healed, or the joy of being a small part of a majestic natural environment, that lets us feel free for small slivers of time.

Kowing knew how to tell stories, fully aware that they were likely shared in some, even many details at levels that transcend our roles in life.

The very last painting Kowing painted has an alpine sky-blue rectangle in the center, an empty space devoid of text, mementos, sorrow.

I try to tell myself that when he walked on in 2016, he stepped through that window into the azure light, breathing the high-altitude ether of not discovery, but release.

If you are interested in seeing work of other contemporary Native American artists, here are just a few options from around the state:

- The Maryhill Museum of Art, which opens again March 15

- The Columbia Center for the Arts in Hood River

- Contemporary Native Voices: Prints from Crow’s Shadow, an exhibit at The Dalles Art Center that runs from February 4 through March 26

- Celilo – Never Silenced, an exhibit opening March 1 at the Patricia Reser Center for the Arts in Beaverton

- Ancestral Dialogues: Conversations in Native American Art, a permanent collection at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem

- The High Desert Museum in Bend