Over a decade ago I exhibited Fugue – The Poetry of Exile at Portland’s Artist Repertory Theatre, photomontage work that attempted to transform poems of exile and displacement, mostly by Holocaust poets, into visual images. The show ran in conjunction with a play by Diane Samuels, Kindertransport, produced by Jewish Theatre Collaborative.

It was early days in my montage-making efforts, with still limited technical skills. But the core components were already in place: visual translation of ideas that invite us, are in need for us to witness.

Here is one of the poems that I chose at the time.

My Blue Piano

At home I have a blue piano.

But I can’t play a note.

It’s been in the shadow of the cellar door

Ever since the world went rotten.

Four starry hands play harmonies.

The Woman in the Moon sang in her boat.

Now only rats dance to the clanks.

The keyboard is in bits.

I weep for what is blue. Is dead.

Sweet angels, I have eaten

Such bitter bread. Push open

The door of heaven. For me, for now —

Although I am still alive —

Although it is not allowed.

by Else Lasker-Schüler (translated from the German by Eavan Boland)

(Here is a link to the German original – it is even starker than the translation, requesting permission for dying)

The poet, Else Lasker-Schüler, is one of those people I’d elect to take with me to a deserted island, an artist, activist, risk-taking, and deeply independent woman who supported socialist causes all her life. She left Nazi Germany in 1933, and ended up eventually in Jerusalem, where she wrote some of her best poetry before she died in 1945. Her friends and literary circle there included German-speaking Zionists, such as Martin Buber, Hugo Bergman and Ernst Simon who, like herself, favored a bi-national Palestine.

I was reminded of the poem when I read the insightful ArtsWatch review of an exhibition currently at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, while staring at another defunct piano during my LA Sabbatical last month (today’s photographs.)

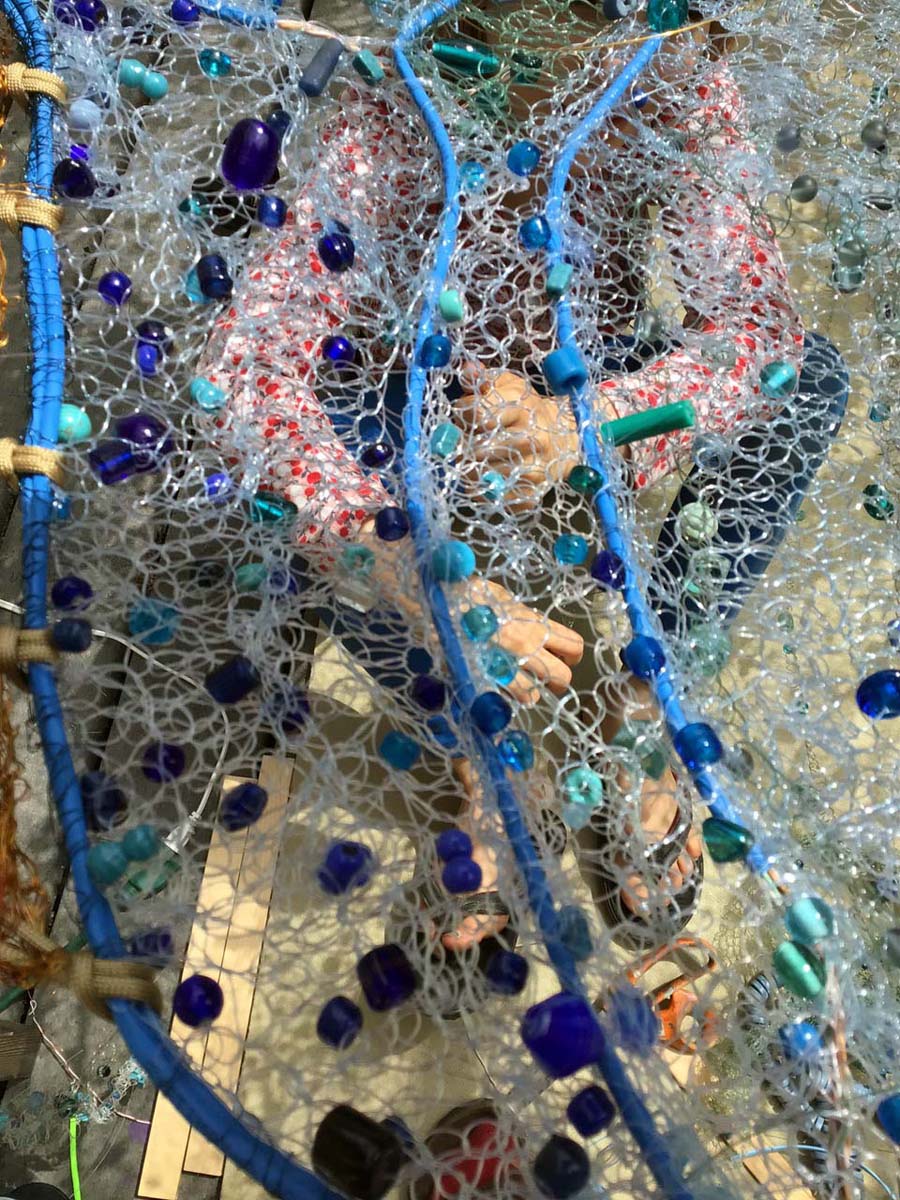

The Burned Piano Project: Creating Music Amidst the Noise of Hate is a collaboration between composer and pianist Jennifer Wright, her husband Matias Brecher and textile artist Bonnie Meltzer. The artists resurrect, refashion, in some ways rebirth a Steinway grand piano that belonged to three generations of a Jewish family whose house in Portland was destroyed by arson in 2022, fueled by antisemitic hate. The torched instrument reemerged as a kind of glassy phoenix from the ashes:

“The Glass Piano was designed to appear as delicate as a glittering butterfly, a creature more of spirit than of the earth, yet it possesses subtle strength and a range of glass rods and hammers and pitched sounds that can be orchestrally combined in unusual ways.”

Meltzer, in turn, created a large tapestry and a smaller banner with inscribed stitching, incorporating wood, torched strings and other bits and pieces of the charred piano into her work.

While the Holocaust poet looks at the remnants of her destroyed life, embodied by the defunct piano, and wants nothing more than for it to end, the two contemporary artists rely on joyful defiance, changing the ruins into some sort of vibrant reminder that the possibility of transformation has not been foreclosed.

One can speculate whether those divergent sentiments are the result of the intensity of the trauma, the actual threat to existence, compared to the reactions of concerned bystanders to the consequences of racist vandalism.

It does not matter, in my mind, though, as long as art forces our own witnessing, insists that we acknowledge the horrors brought by war and hate.

This is central to the work of Jorge Tacla, whose art I continue to explore. His focus on ruins is one of the main themes of another exhibition, A Memoir of Ruins, currently on view at the Coral Gables Museum in Florida. His paintings offer a veritable graveyard of bombed and destroyed architecture across the Middle East, war memorials of a kind that mourn the victims rather than celebrate the victors (if there are any, given the centuries of strife built into the conflicts.) I won’t be able to visit, but I strongly urge my readers in the Miami vicinity to go and take it all in – you have until October 27th, 2024. It is timely work in the light of ongoing destruction of entire swaths of land made uninhabitable by warfare, erasing life, mirrored in paintings devoid of human figure.

The imagery acutely remind us of the violent urge to reduce everything possibly connected to human habitation, urges acted upon by various warring powers. They spring from the wish to annihilate not just human beings, the declared enemy who shall be starved, maimed or killed, but also all that could provide a basis for resurrection of a group with a given identity. If you bomb houses of worship, schools and universities, the libraries, the museums, the archives, all the repositories of cultural, historical and personal memory into oblivion, you generate a displacement that goes beyond loss of place – you truly vanquish the soul of a people.

Tacla’s work is the opposite of what has come to be known as “ruin porn,” the depictions of desolation as a backdrop in artistic endeavors, be they classic paintings that centered ruins as moralistic symbolism, or the photographs of urban decay, or the film sets for dystopian science fiction movies. Capitalizing on the visual salaciousness of melancholic imagery, while ignoring the forces that brought the world to ruin, from poverty to warfare, stands in stark contrast of what Tacla does. Without being photorealistic, the canvases convey a sense of absolute erasure, seamlessly merging into the actual visuals from places like Syria and now Gaza, that hit our screens. There is nothing of the frisson we so cherish when observing something slightly alarming from a distance. There is just dread, slowly seeping into your system, if you stand for any amount of time in front of these monumental canvases.

Our fascination with ruins – as long as we don’t have to live in or next to them – has been an artistic staple since the Renaissance. The focus during romanticism shifted to the potential for renewal. After world war II it became a national rallying cry, like Auferstanden aus Ruinen, From the Ruins Risen, the title of the German Democratic Republic’s Anthem from 1949 to 1990.

We might do well to shift our focus yet again, from ruins to the looming possibility that at some point renewal is no longer possible. At an age where weapons of mass destruction can wipe out life as we know it, we can hit a point of no return. We have certainly gotten sufficient warning. If you look at the aftermath of Chernobyl, not just in the exclusion zone for Reactor 4, which has become a pilgrimage site for disaster junkies, but in the forests surrounding the nuclear power plant, you’ll find some stark revelations (hard now under Russian occupation.) The trees downwind from Chernobyl all died immediately after the disaster. With the entire landscape poisoned, the agents of decay and thus eventual renewal, have also ceased to exist. No more bacteria, fungi and insects that usually recycle a forest’s nutrients and rid it of debris to prepare for new growth. They, too have been erased, and so you are left with ruins that will practically last forever, dead matter that will not renew in any form, looming over our very own extinction when war descends in its final form.

As I have so often stated here – fully aware how many of my readers disagree – I don’t believe art per se can change things, be a political force of the needed magnitude. But it can be a canary in the coal mine, helping us to start questioning, figure out causal connections, and at least implores us to think about solutions that exclude future ruins once and for all.

The rest is on us.

Here is a Pavane by Fauré.