“Our mission is to collect, preserve and share the stories, oral histories and artifacts of Portland’s Chinatown as a catalyst for exploring and interpreting the history of past, present and future immigrant experiences.” – Portland Chinatown Museum (PCM) Mission Statement

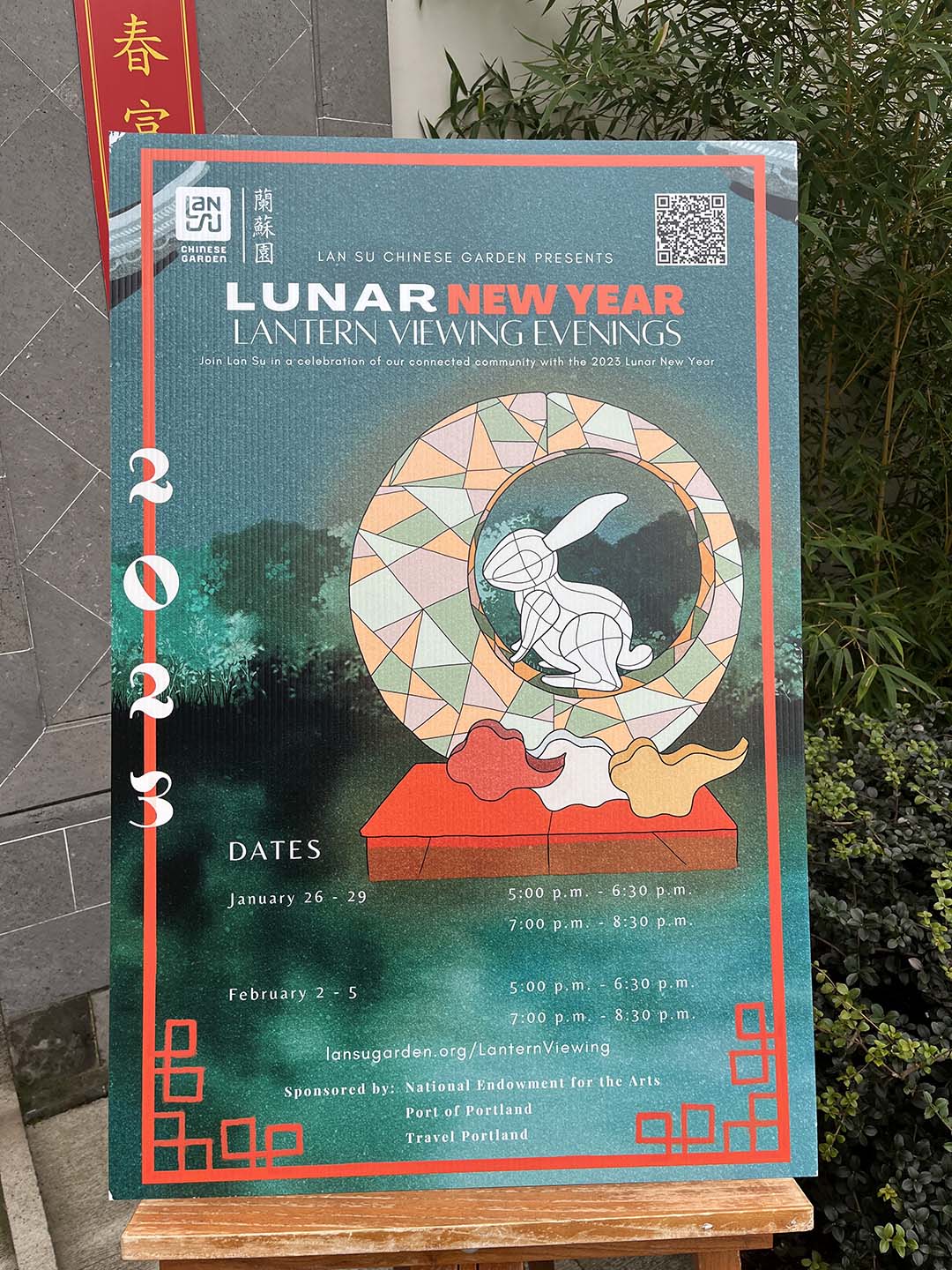

The Lunar New Year – The Year of the Water Rabbit – started yesterday and the Chinese government expects about 2.1 billion journeys to be made in Asia during a 40-day travel period around the celebration as people rush back for the traditional reunion dinner on the eve of the new year. I took a short trip to Portland’s Old Town Chinatown instead on Friday, an annual pilgrimage to admire the beauty of Lan Su Chinese Garden with its festive decorations for the occasion.

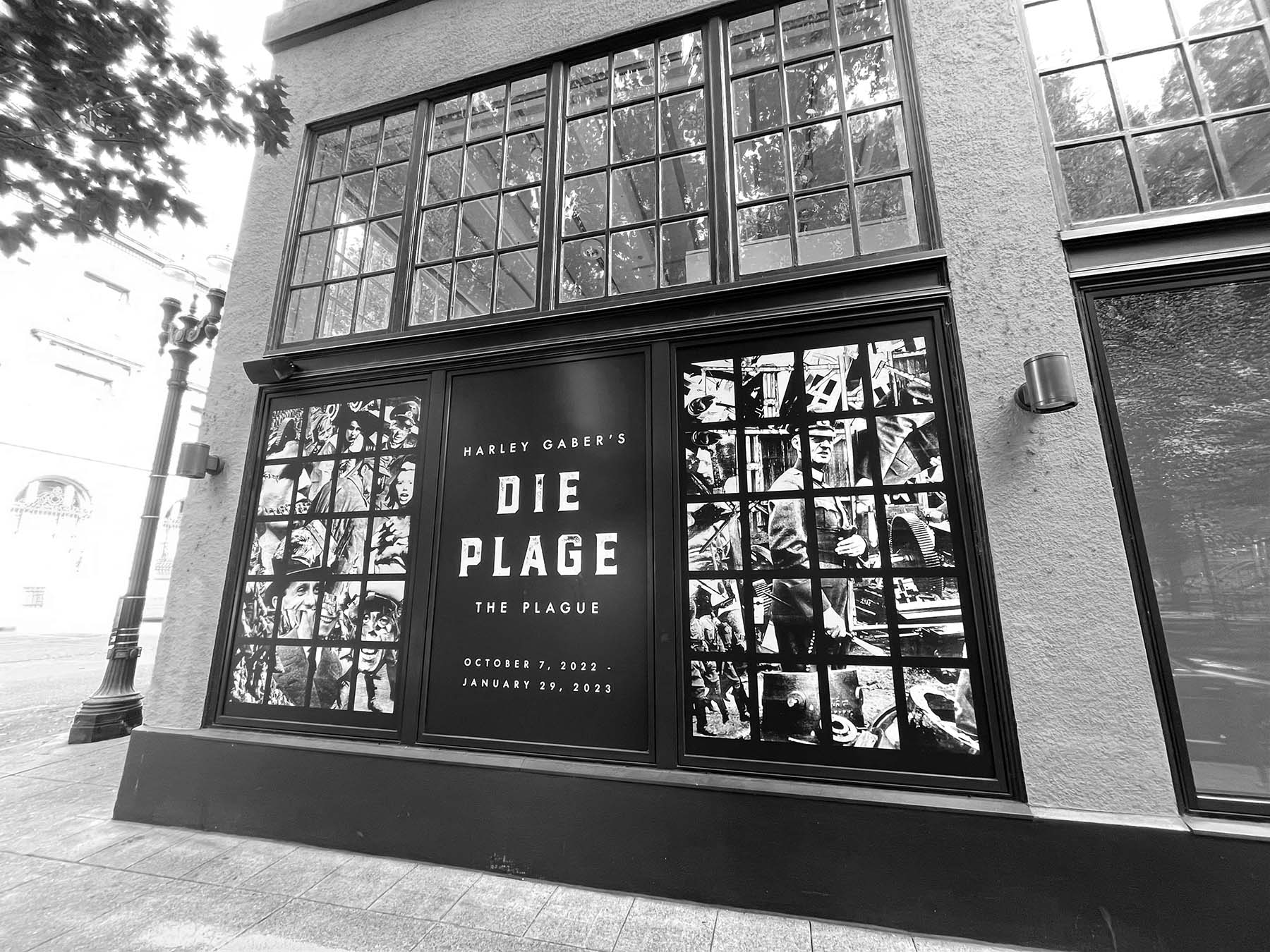

This year I added a second stop, a first visit to Portland Chinatown Museum (PCM,) which is just a block away on NW Third Ave, and not too far from the Chinatown Gateway. The museum opened in 2018 and did not appear on my radar during the pandemic years. I cannot recommend a visit strongly enough: opening hours are limited from Friday to Sunday, and the current temporary exhibition will close on January 29th. So if you can, make it down there next Friday or Saturday between 11 am-3 pm, there is some revelatory art on display.

The history of the museum’s founding can be found here. Like other Old Town institutions devoted to collecting and preserving immigrants’ histories, the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education among them, PCM offers a permanent exhibition depicting the lives and plight of the Chinese immigrants. Beyond the Gate: A Tale of Portland’s Historic Chinatowns provides a comprehensive look at historical artifacts, some arranged in diverse dioramas, and guides you through the various aspects of the immigrant experience with informative exhibition texts and archival photographs.

***

Two separate galleries provide space for the work of contemporary Asian American artists, currently showing Illuminating Time, installations by three different artists-in-residence working with different media. The exhibition is exquisitely curated by Horatio Law, one of the PNW’s premier public art and installation artist who serves as the Artist Residency Director. It echoes the permanent exhibitions’s themes of loss, hope and belonging, so familiar to all immigrants.

___

一方有难,八方支援 “When trouble occurs at one spot, help comes from all quarters.” – Chinese Proverb

The theme of community, integral to collectivist cultures and so prominent in the museum’s permanent exhibition of historic Chinatown’s structural support systems, is picked up by Alex Chiu. Known to many of us for his vibrant murals that can be found across PDX, he undertook a series of ink drawings of community members that are displayed in the entrance hall of the museum. Placed against the backdrop of a stylized rendering of the Chinatown gateway, they depict a range of characters of all ages and degrees of visibility, pointing to the diversity of Portland’s Chinese population. Expressive and detailed, these portraits are a lively counterpart to the archival photographs of the Chinese ancestors who set foot here in the 1800s.

The juxtaposition between the traditional valuing of community and the artist’s modern ways of portraying individuals reminded me of the current trends in social psychology exploring the status of young Chinese who grow up in a world where the traditional collectivism of their culture and the modern demands and offers of Western individualism intersect. It is interesting work, based on spontaneous recollection of Chinese proverbs by these college students, reflecting which values come to mind first and how they are weighted. A changing world, yet heavily anchored still in tradition.

Clockwise from upper left: Portland Chinese Community Portrait Series: Billy Lee, Beatrix Li, Roberta Wong, Terry Lee.

***

“Take care of each other. Take care of the soil.” Shu-Ju Wang, in conversation.

Off to the side of the front venue is a room dedicated to Shu-Ju Wang‘s exploration of the history of Tanner Creek and its connection to the Chinese laborers and farmers who tended to its surrounding fertile soil to grow vegetables for both, sale and consumption. Her installation consists of multiple parts, prominently displaying a wooden slide constructed to represent the topography of the waterway with its angles and gradient. It is actually a marble run, and visitors are invited to play around, connecting through interaction. Above it hangs a mobile, made from silkscreen and gouache with a top part that was embroidered on paper tinted with gouache as well. It represents rain drops, a sense of fluidity enhanced by the aqua color range and the lightness of the material that slightly trembles in the draft. The sturdiness of the wood and the fragility of the paper assembly complement each other, rather than being opposed, representing aspects of nature that remind us of its power as much as its vulnerability.

Wang’s interest in and facility with science is evident in the exhibition posters that provide facts about the history of the creek within the build-up of Portland, the encroachment endangering the creek’s initial free run and displacing those human communities that had respected natural cycles of flooding necessary for fertile ground. Creatively, these narrative are told in letters from the creek to us, making a personal statement in a voice that I can see as particularly effective for young minds, children feeling addressed and drawn in. That said, it sure got my attention. The remaining walls are hung with the artist’s recent paintings and printings of nature-related topics, the theme of the need for environmental stewardship pervasive, meticulously and insistingly expressed.

Left to right: A fold-up book Castor and Sapient; A Study of Home (2021) Silk screen, pressure print and collage; a basket by Sara Siestreem (Hanis Coos) woven from native plant materials to catch the marbles.

I walked out with a plant cutting in hand, small annuals which are offered for free – by March, when this part of the exhibition is likely still on, it will be vegetable plantings to connect to the Chinese farmers’ history at Tanner Creek.

***

” …and someone far away will see flight patterns,” – excerpt from Sam Roxas-Chua’s poem Please Be Guided Accordingly.

If we link the immigrant experience to the past, present and future, as the museum intends to do, then Wang’s depiction of the past and Chiu’s capture of the present is joined by Roxas-Chua’s work incorporating the future. That might seem counterintuitive given the prevalence of allusions to memory, including the title for some of the major works.

Yet I was flooded with an impression that the work was about opening towards something, with the release that comes with the acknowledgement and acceptance of grief.

Detail: Gold Lighting and Lullaby Scripts

Part of that might have been triggered by the realization of the ephemeral character of both materials used and conceptual expression. The artist will destroy all that was presented by the end of the exhibition’s run and bury it at its source, the places in nature from which materials for the ink and paper were borrowed, and from which the inspiration was drawn. What is gone makes room for the new.

Left and RightL Gold Lighting and Lullaby Scripts. Center: Stone Satellites over an Excavation Site in John Day, Oregon.

Part of it can be found in the way Roxas-Chua’s calligraphy is open to interpretation. The technique of asemic writing that he uses is a form of communication that is unconstrained by syntax or semantics, an aesthetic rather than a verbal expression. It is the perfect medium for someone who is overburdened by the demands of too many languages (In Roxas-Chua’s case four) or too little rootedness in each.

Excerpt: Three Oranges and Blue Mountains Moon

For the viewer this opens space to connect to the calligraphy in ways unrestricted by formal demands. Unsurprisingly for me, who has spent her scientific research years studying memory, the art appeared as patterns of synaptic connections, but also of plaques causing retrieval failure, of parallel processing and encoding bias. The malleability of memory was perfectly caught in the flow of these marks, the way how present context is re-shaping, even altering what is remembered, ultimately influencing an assessment of the future.

How we approach the future is not just guided by how much our memory has changed over time, shifting away from facts and towards a narrative that helps emotional adaptation. How much any of us can remember the specifics of our past also plays a big role.

In many realms, all of our thinking about the future is rooted in memory. Policy planners, for example, routinely contemplate past patterns as a way of anticipating things to come. At a much more personal level, researchers suggest that a sense of hopefulness, or its lack, depends on how specifically we remember the past. Think about someone saying, “I cannot see how that could possibly happen,” or the opposite, “I can easily imagine how that can come to be.” That step of imagination is arguably central to how hopeful someone will be about the future, or not. And that ability to project is clearly linked to the specificity of your memory of how things unfolded in the past. Remembering opening the path to hope.

Excerpt: Three Oranges and Blue Mountains Moon

For the artist it was perhaps a way of connecting to the various landscapes and human sources that linked to the past of Chinese immigrants, from John Day to Astoria, where he interviewed people and recorded soundscapes of the environment (QR codes direct you to a listening experiences that captures these sounds, or music, or the artist’s poetry, providing additional levels of experience of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the totality of each artwork.)

Loss and re-emergence are central to the work. It was, I believe, most urgently captured in The Weeping Script. Please Be Guided Accordingly, the poem that accompanies the calligraphy, seizes the stages at which death rips a loved one away from you, bit by bit. There’s a release provided by inklings of hope and uplift in the future, though tempered by the knowledge that it will be a cold, lonely run. Maybe not the entire three year mourning period proscribed by Confucius, but the concession that grief exists and yet can be turned around. It calmly points to opening of new horizons.

For anyone mourning it will be brutally moving, and yet it is incredibly beautiful, hopeful work.

***

And now we turn to the elephant in the room. If the consummation of loss is part of the art inside the museum, wait until you see it instantiated in the suffering of the houseless in real life outside. The many houseless in the neighborhood, their tents, their misery, their detritus, are something the Old Town businesses are trying to deal with.

City plans almost a decade in the making have not yielded visible results, even though the mayor’s office claims progress. In October 2021, spurred by the rise in crime, violence and public camping in the Old Town neighborhood, the leaders of four cultural institutions — Lan Su Chinese Garden, the Japanese American Museum of Oregon, Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education and Portland Chinatown Museum — wrote a joint open letter asking each city and county commissioner for immediate help. In March of last year, Old Town Community leaders unveiled a plan to repair and reopen the neighborhood, which included goals like reducing 911 call answering times, improving lighting in the area, and reducing tent camping by one-third.

The right words were said: “As Portland’s oldest neighborhood, home to immigrants who overcame decades of discrimination and indignity, and today, home to so many who are fighting just to stay alive, we must to whatever we can to respond to the crisis of humanity unfolding around us. And we must do it today,” said Elizabeth Nye, the executive director of Lan Su Chinese Garden, “the local government’s inability to safeguard Old Town disrespects its history.It is particularly devastating to our houseless neighbors who deserve more from their government.”

Mural on NW Davis St

The subsequent reality, however, amounted to an exponential increase in sweeps of the neighborhood. The 90-day “re-set” led to a particular form of camp removal, structure abatement sweeps, that can be ordered by the police chief or engineers in two different bureaus overseen by city commissioners. The standard Homelessness and Urban Camping Impact Reduction Program, or HUCIRP, sweep provides at least 72 hours’ notice to unhoused Portlanders so they can gather their belongings and voluntarily move before city contractors remove them from a given area. The structure abatement approach extends 1 hour warning, if that. If you happen to be away from your tent or belonging, all is lost. (For a detailed description of the way things unfolded last summer, here is a report by advocates from Streetroots, an organization where I taught writing workshops for the houseless until the pandemic started.) Shelter referrals given during or after sweeps are not enough – you can stay for one night, after having been completely uprooted. Many feel unsafe in shelters even for that one night, or can’t apply because they have pets.

Mural on NW Davis St depicting the view South on NW 4th Ave

Do these sweeps help solve the situation? Of course not. They clean up the streets for a short time or for a particular event, while making people less stable, re-traumatizing them, and shifting the entire problem just to a different location. Mayor Ted Wheeler and Commissioner Dan Ryan’s five October 2022 resolutions on homelessness included a ban on unsanctioned camping and the construction of compulsory mass homeless encampments, which would host up to 250 people. This can only be seen as a way to circumvent the Supreme Court decision letting the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals re Martin v. Boise decision stand, stating that a houseless persons cannot be punished for sleeping outside on public property in absence of alternatives.

Mural on NW Davis St

Of the six promised safe-rest villages only 2 have opened so far. Evictions from rental properties have skyrocketed since the renter protection during the pandemic was lifted – in the first 10 months of 2022 alone there were 18.831 evictions, as reported by a PSU research group. According to the 2022 Multnomah County Point-in-Time Count report, 24% of those experiencing unsheltered homelessness reported COVID-related reasons as the cause, adding to increased inflation and rising rent costs. Despite the stereotype, these are not all people with criminal records, or mental illness, or living with substance abuse problems. And even if they were, they would have the same human right to shelter as we all do. On top of it all, Senator Wyden’s DASH Act, (Decent, Affordable, Safe Housing for All) languishes in committee, even though it has support from all sides, business owners, land lord organizations and advocates for the houseless included.

I completely understand the need for businesses and institutions to be able to function in a safe environment and one that does not interfere with business under the specter of violence and crime. But let us acknowledge that the reaction so far has been to try and disperse the unhoused, without providing sufficient, actual housing, the only permanent solution to homelessness.

Archival photograph of NW Fourth Avenue

Until something changes structurally and expediently, I fear museums like the Portland Chinatown Museum will not get the exposure they deserve because many people hesitate to visit Old Town. It is truly sad, given what is on offer. But it is heartbreaking to see the suffering and loss in the surrounding streets, with poverty levels probably comparable to those experienced by the very first Chinese immigrants that came to seek a better life in a new home, leaving famine and disease behind. Past, present and future connected at the most basic level of human experience, daily survival.

Portland Chinatown Museum

127 NW Third Avenue

Portland, OR 97209

Friday – Sunday

11:00 AM – 3:00 PM

Docent-led group tours are Friday through Sunday by reservation only.

Current exhibition Illuminating Time closes on January 29th.

Join the museum on Saturday, January 28 at 10:00 a.m. for the seventh annual Lunar New Year Dragon Dance Parade and Celebration, presented in partnership with the Oregon Historical Society.

The 150-foot dragon will be celebrating the holiday with lion dancers, performers, and a lively community parade through Old Town, Downtown, and up to the Oregon Historical Society Park