Endless Pigeons.

· Malia Jensen at The Reser ·

“To be full of joy when looking at an oeuvre is not a little thing.”

~ Jean (Hans) Arp “Jours effeuillés: Poèmes, essaies, souvenirs.” (1966.)

***

Full of joy about captures my emotional reaction to Malia Jensen‘s newly installed sculpture at the Arts Plaza of The Reser, her contribution to the many works of art displayed across town during the next weeks in the context of Converge 45‘s Biennial. Endless Pigeons is such a clever sculpture, subversive and learned alike in the way it combines subject, form and a slightly altered utilitarian object for its pedestal.

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (2023)

Her commissioned sculpture riffs off one of Constantin Brâncuși‘s most famous works, the Endless Column from 1937. The 98-foot-high column of zinc, brass-clad, cast-iron modules threaded onto a steel spine is part of an installation of three sculptures commemorating Romanian soldiers fighting in WW I. Recently restored after years of neglect, vandalism and governmental condemnation as “degenerate art,” Brâncuși’s sculpture can be visited in Târgu Jiu, Romania. (Actually, this one is the last in a series of endless columns dating back as early as 1918, made of wood, with several others following, two of them around 1928 that are 10 ft and 13 ft tall respectively, and for the first time placed on square pedestals. Both can be seen at the Musee National d’Art Moderne in Paris.)

Constantin Brâncuși Endless Column (1937) – Photo Credit: Mike Masters Romania (CC BY-SA 3.0 RO)

Jensen’s column is not quite on that scale, and the elements consist of eight humongous representational pigeons rather than abstract geometric modules, but I take joy over awe any day.

There is a bit of tongue-in-cheek rebellion towards the giant of art history (or perhaps the fan boys of “famous” art in general) in choosing the lowly bird as a replacement, although “lowly” depends on the eye of the beholder and the context. Watching flights of band-tailed pigeons is inspiring, if only for the noise their bodies make. Wading through throngs of tourists in European cities taking pictures among the flocks is quite the adventure, particularly when enthusiastic photographers enamored with individual birds become a tripping hazard.

The perennial pigeon man at the Louvre, Paris; tourists on St. Mark’s Place, Venice

XL Pigeons elevated to art, with the real thing blithely ignoring the gilded additions to its perch. Town hall roof in Alkmaar, Netherlands.

In Portland, a city that has made the meme “put a bird on it” its own – often accompanied by condescending smirks – putting one bird on top of another shows welcome contempt for what is considered worthy art – or not. Jensen’s sculpture evoked in me such a strong sense of the artist’s love of nature, her desire to show the beauty in the ignored or overlooked, her playfulness in the arrangement of the birds, and her skepticism as to who gets to define “art,” that it simply lifted my spirits.

The size contributes; previous works that offered visions of piled-up birds were smaller and somehow more tender. The current large birds almost beckon you to touch them, feel their ridges and explore their patterns with your fingers, a haptic experience made possible by the sculpture’s accessibility. Their bronze plumage shows plenty of detail with a patina that might soon be altered by chance contributions dropped by avian neighbors from the small urban wetland nearby.

Malia Jensen Small Pile, (2010) Bronze 10 1/4 x 6 x 5 inches

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (1923) Details

Birds have, of course, played a major role in art, and significantly so with multiple contemporaries of Brâncuși within the surrealist movement. Leonora Carrrington used them as a frequent motif in her paintings and lithographs, and I found one of my favorite bird paintings ever in the Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, Mexico: Remedios Varo‘s Creation of the Birds.

Left: Leonora Carrington Steel Bird (1974) Lithograph on Paper. Photo credit Sotheby’s.

Right: Remedios Varo Creation des las Aves (1954) Oil, Masonite.

They were a central topic for Max Ernst, who relates his obsession with them to the childhood trauma of losing his beloved pet bird at the time of his sister’s birth. For Ernst, birds became symbols of both victimhood and freedom, used in his art as an alter ego, often representing a rising phoenix from the ashes. (I picked an example that mostly resembled a pigeon, photographed at a Hamburger Kunsthalle exhibition, I believe of the Collection de Menile in the early 2000s, I lost my notes. The other images are from a 1975 book of edgings, Birds in peril.)

Max Ernst Oiseaux en péril (1975) Color etchings – Oiseaux spectraux (1932) Oil on cardboard.

Brâncuși, whose work is frequently referenced by Jensen, was preoccupied with birds as well. He was interested in their movement, however, not the way they looked. His series of Bird in Space representations, seven of them in marble and 9 cast in bronze, takes off the wings altogether, streamlines the bodies and adds just an oval plane for a head. The creatures soar, more akin to rockets, really – here is an example from the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, CA.

Constantin Brâncuși Bird in Space (1931)

The artist was also questioning the traditional way sculptures were displayed, on top of a pedestal that signals the artistic value of a piece, aiming at ennobling it, elevating it out of reach in ways that confer the preciousness of the object (or the memories it represents.) His contemporary, sculptor and poet Hans Arp who I quoted at the beginning, was even more opposed to traditional pedestals. (Details can be found here.) He felt they enhanced an aura that separated the experience of art from other experiences we have in our lives, distancing us from the work in ways that had to be overcome. In fact, he loathed the way art, put on a pedestal, glorified people – often the very people who brought disaster upon us, just think of all those sculptural memorials to generals and colonialists.

“Since the time of the cavemen, man has glorified himself, has made himself divine, and his monstrous vanity has caused human catastrophe. Art has collaborated in this false development. I find this concept of art which has sustained man’s vanity to be loathsome.”

– Hans Arp “Jours effeuillés: Poèmes, essaies, souvenirs.” (1966.)

Abandoning aloofness in favor of enhancing participatory interaction with the art work was the goal. That included ways of encouraging the viewer to circumnavigate a given sculpture, looking at it from different viewing angles, and not being ruled by a fixed position in space. Employing something more akin to utilitarian objects was also believed to help overcome the distance between viewer and object, given that it was less of a demarcation and more of an invitation given the established familiarity.

Jensen’s Endless Pigeons makes great use of these markers that encourage participatory engagement. Her “pedestal” turns out to be one of those traffic barriers, albeit foreshortened, that tell you to stay in your lane, but here, in welcome reversal, functions as an invitation to cross over line that separates art from everyday life.

Stacked Jersey Barriers

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (2023)

The way she arranges the pigeons also invite the viewer to walk around the sculpture, wondering about the balancing act exhibited in that column. I ended up speculating about the single, straight backward looking pigeon: an avian representative of Klee’s Angelus Novus, the angel of history always looking backwards towards the past, although he has his wings straight up, if I remember correctly?

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (2023) Detail

Circling the sculpture – although these tracks were made by the machinery that installed it, not the author.

Viewing the sculpture from above somehow enhances the sense that the column is slightly teetering and the birds flapping their wings to attempt balance. There is humor here, some distinct signal that we can’t take everything too seriously, (ARRRRRT, as the inimitable Molly Ivins used to say,) and should not cling solely to depictions of the problems of our times.

But there is also the reminder that not only do we, whether scientists or artists, stand on the shoulder of giants, but that the balance needed to achieve the heights we want is inevitably coupled with trust and cooperation, the whole in need of reliable parts.

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (2023) Detail

A column of animals perching on each other is a familiar symbol of the power of solidarity for any child raised in Germany. The Brother Grimm fairy tale The Town Musicians of Bremen relates a story of abused and condemned, aging animals banding together and running away from their farms. With combined forces and a bit of slapstick luck worthy of the Dadaists theory of chance, they get rid of a band of robbers that terrorized the town. The donkey, the dog, the cat and the rooster live happily ever after, wouldn’t you know it. Immortalized by sculptor and Bauhaus Master Gerhard Marcks, the sculpture of their heightened power achieved through mutual aid was placed on the Bremen town square in 1953. (The city, by the way, also houses a museum in his honor that has become noted for exhibitions of modern and contemporary sculpture.)

Gerhard Marcks Bremer Stadtmusikanten (1953) Bronze.

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (2023) Detail

***

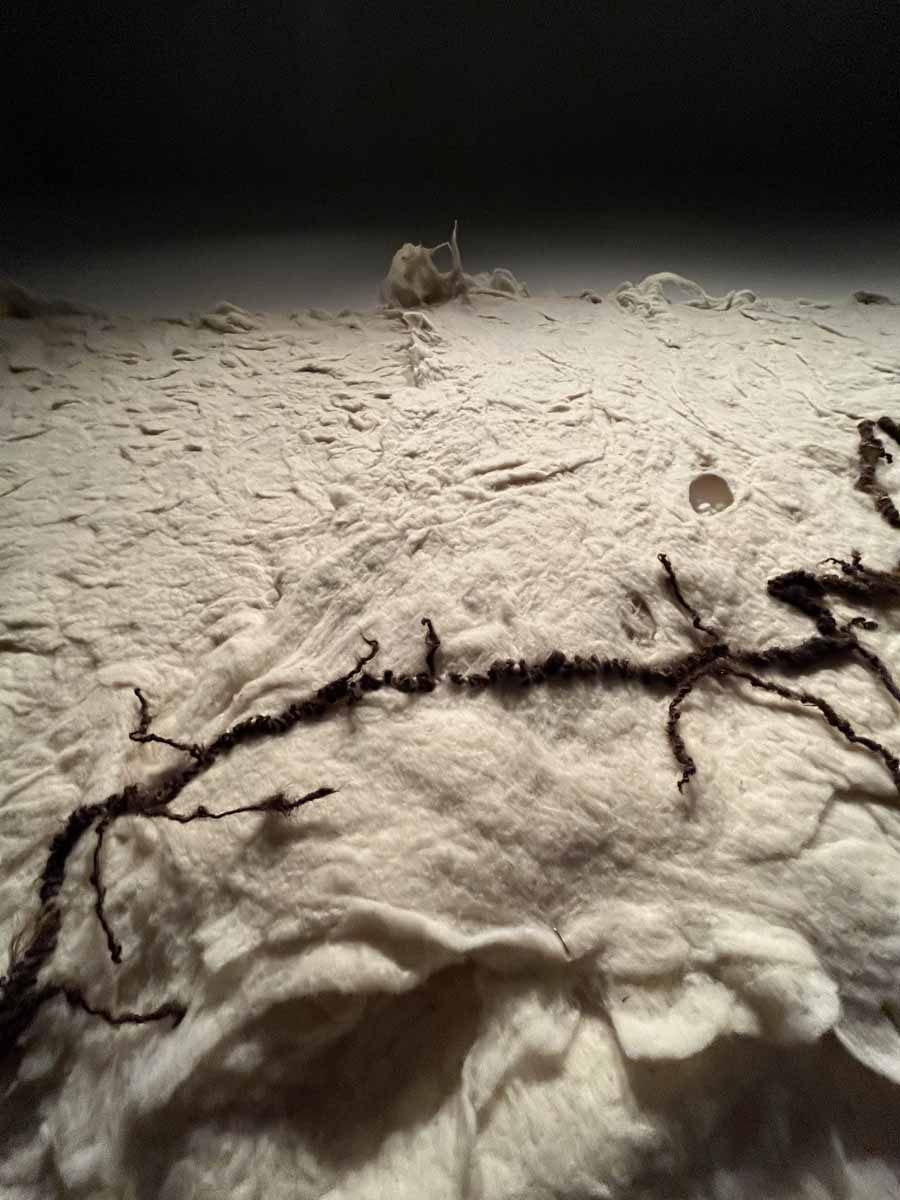

Many of the European artists in the 1930s, when fascists started to move things towards inescapable horror and destruction, showed a renewed interest in nature and its essential value. Hans Arp certainly stressed the importance of unity between man and nature, and many of his sculptures of that era were artistic expressions of those beliefs. One of them, To be Exposed in the Woods, brings me to Malia Jensen’s recent work that is challenging to grasp, in more ways than one. I want to explore it here, because I see a direct link to the work displayed at The Reser. Just give me a minute to set the stage.

To be exposed in the Woods (looking indeed like a partially consumed salt lick out in the woods) came to mind when I thought back over Jensen’s oeuvre Worth your Salt. If you think the pigeons at The Reser are humongous, wait until you grasp what went into the video that Jensen produced starting in 2016. Driven by a sense of a nation mired in divisiveness, a latent disquiet about where we as a country were heading, she turned to nature, hoping for a sense of harmony as well as an embrace of uncertainty and discovery. The artist carved 6 body parts out of large salt licks, with a head that was once again a nod in the direction of Brâncuși or maybe Giacometti, a hand offering a plum, a foot, a breast and a stomach represented by a stack of donuts. (You might have seen that piece at a 2022 show at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at PSU, reviewed in ArtsWatch here.)

Malia Jensen Worth your Salt (Nearer Nature project, 2018 – 2022) (All project photos and screenshots credited to Jensen’s Website or lecture videos.)

She then needed to find locations across Oregon that would provide access to animals interested in the salt licks, prevent hunters or vigilantes from easily accessing vulnerable pray (private or land trust land desirable), allow her to place multiple video cameras (18!) with motion sensors that would record the wild life, in positions with maximum light effectiveness, and then be able to come and go frequently to exchange the SD cards of the recordings for months on end.

All that required interaction with previously unfamiliar people, traversing stretches of land with populations not necessarily used to environmental artists, and eventually cataloging, cutting and editing the 10s of thousand of videoclips with a team of multiple assistants to braid into a final video of some 6 hour duration. This video was then displayed in carefully selected locations that included rural grocery stores and bars, elementary schools, the research facilities at OHSU, chocolate stores, mental health clinics and son on, in hopes of instilling a sense of harmony in viewers, or at least curiosity about the unfolding displays of nature, and maybe fill some of the emptiness left from exposure to a world that has us reeling and insecure, if not frightened.

Here are some of the images captured by the cameras. Overall the fauna was diverse, turkeys, bobcats, coyotes, deer, squirrels, a brown bear and, yes, band-tailed pigeons! on the coast, all making an appearance.

Malia Jensen Worth your Salt (Nearer Nature project, 2018 – 2022)

The assumption was that it was a fair deal – the animals, gifted with the needed minerals from the salt licks would in turn provide the artist with footage that would allow people to be alert to the wonders of nature, in an age where species are disappearing at an unprecedented clip. In turn, increased engagement for the preservation of nature might be triggered by the awe instilled by observation. At least that is my understanding of the core idea of the project.

Why am I then, despite my admiration for the conceptual richness and the insane amount of work going into all this and the wit instantiated in the donuts, for example, feeling unease about what went on? I think it has to do with the nature of surveillance.

If you yourself go out into nature, photographing nature, or wildlife in particular, there is a shared space, a shared risk, a one-on-one encounter that somehow shapes the relationship between you and the animal. This is particularly true when there is eye contact.

May 2023 Oak Island Loop, Sauvies Island, OR

That precludes, pragmatically, the acquisition of the amount of footage and the diversity of wildlife on display in Jensen’s work, of course. So if we grant license to work with automated surveillance instead, and use salt as a lure to maximize the encounters, then we could argue, ok, they got something in turn. But here is where things shift: when the salt licks had taken on a particularly pleasing aesthetic, they were removed to be cast in glass, themselves becoming objects of art of a more permanent and transactional kind. (This was originally not in the plan.) Will those exhibits still confer the ideas that motivated the Closer to Nature project to begin with? Where the critters cheated out of the rest of their supplementary diet?

The hand and what was left of the head top right.

It is certainly obvious when you hear Jensen talk about the work, that it imprinted on her soul, moving her, sustaining her through the years of pandemic isolation, so I am not suggesting mercenary intentions. And in any case, artists have to make a living and should sell their art. It also likely brought meaning to many of the people who were able to see the video or the casts. It just feels like animals have not been able to escape the impact of human “progress” and expansion, threatened or dislodged from their habitats, burnt, starved or suffocated by the environmental destruction we have unleashed. Now we spy on them in their remaining spots, lured there by promises of years, not months, of NaCl. Not that they care, they wouldn’t know, of course. It is more about introspection into our own ethical parameters that might or might not be violated when we, too, engage the tools of surveillance that many of us so rage about within the power structures where we humans live and move.

Which brings me back, in case you were worried, to the pigeons. I cannot tell if the expressed deep love for nature was always there or was enhanced by Jensen working on the Nearer Nature project. It is clearly on display in her choice of sculpting the Endless Pigeons, no matter how humorous or ironically it is to be received. I also feel that the decision (and, yes, courage in today’s art world) to create something joyful, vibrant, somehow optimistic (as this column came across to me) is potentially the result of having been given the gift of watching harmonious interaction during her video recording. Not all is doom and gloom. Watching deer and coyote peacefully cross paths at night reminds you of that.

I remember photographing this window display in a small shop in France, that added the “lowly” pigeon to the exterminator’s list among the cockroaches and rats, and thinking, “Hah, they’ll outlast the last of us. No matter how we try to prevent them from nesting, feeding or defecating by hammering nails into windowsills or providing netting for the vulnerable buildings, they’ll reproduce!

Pigeons roosting on a French cathedral

Malia Jensen Endless Pigeons (2023) Details

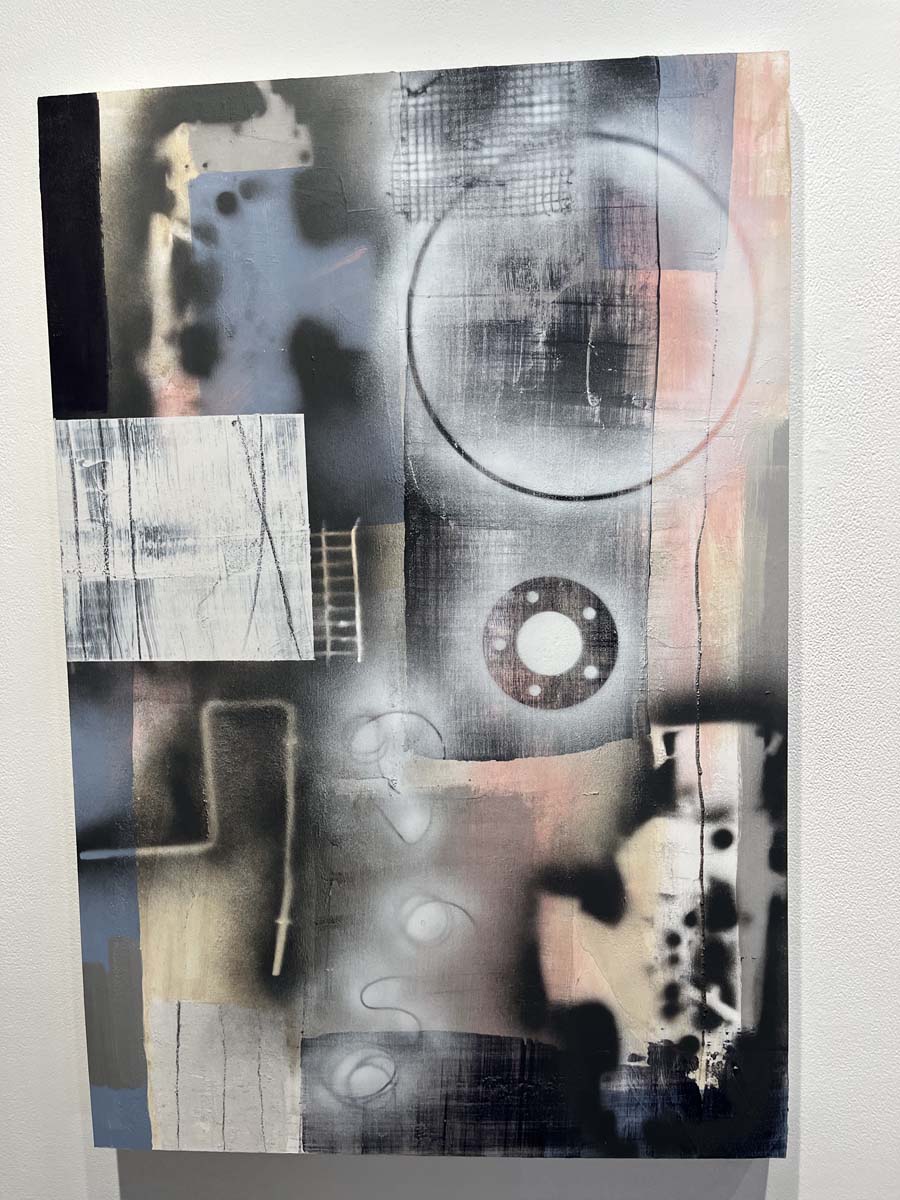

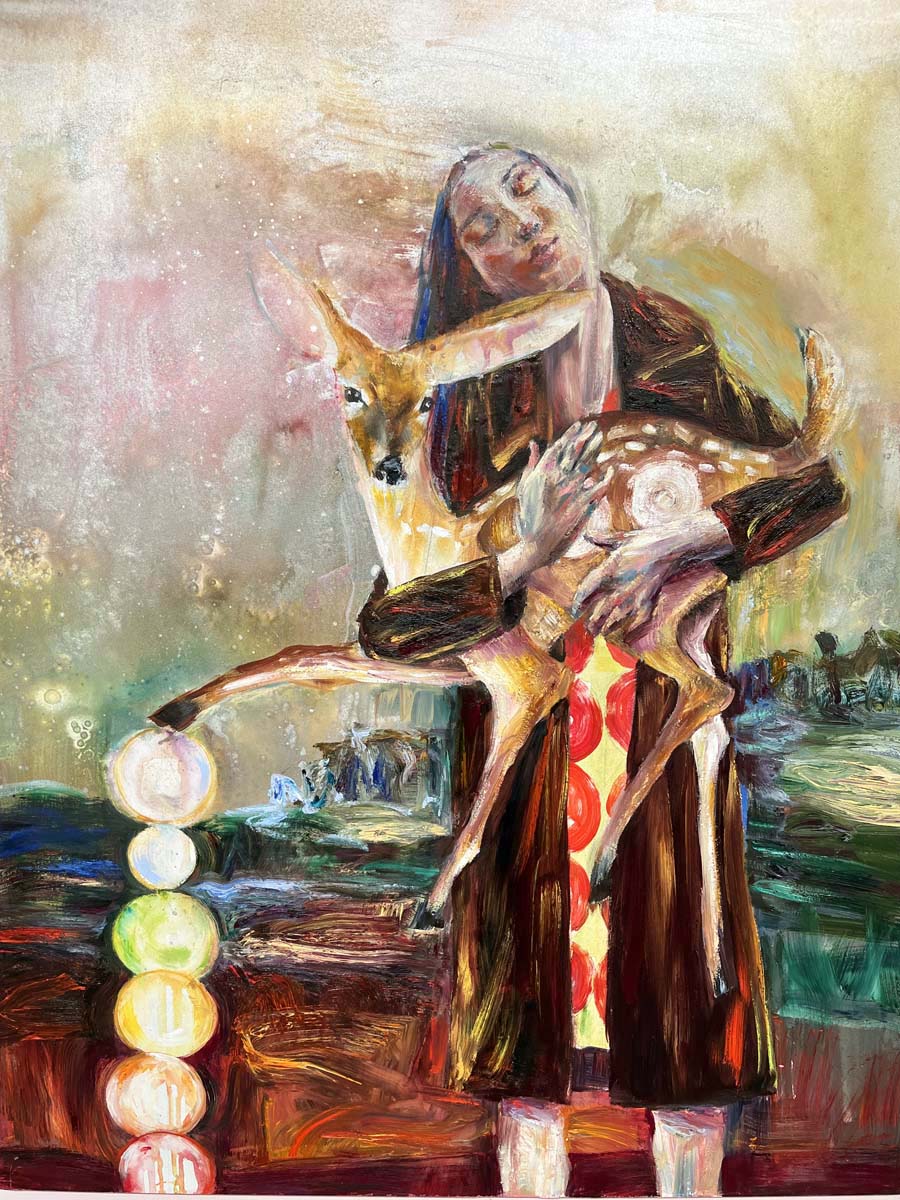

I can only speculate why this sculpture was placed at The Reser. A practical location? A relation to the environment? A counterbalance to Jorge Tacla’s work inside which confronts us with the dark side of humanity? (I had written about his remarkable paintings previously here.) A result of the fact that both artists are represented by Christin Tierney Gallery in NYC? Who knows. The choice was perfect. We need some straightening to navigate the art world and we need resilience to make it through these times. If anything speaks of resilience, it is pigeons! And they bring joy. Not a small thing.

My daily visitors, band-tailed pigeons.

Converge 45: Public Opening Weekend Celebration at The Reser: Saturday, August 26 @ 10:30 am

Malia Jensen: Artist Talk :September 21, 2023 6:30pm at The Reser

SOCIAL FORMS: ART AS GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP

- Where: The Patricia Reser Center for the Arts, 12625 S.W. Crescent St., Beaverton

CONVERGE 45

- What: A Biennial exhibition of work by 50 artists in 15 venues across greater Portland, curated by Christian Viveros Fauné

- When: Opening Aug. 24-27 and continuing with various closing dates through the end of 2023