Wild Geese

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

By Mary Oliver

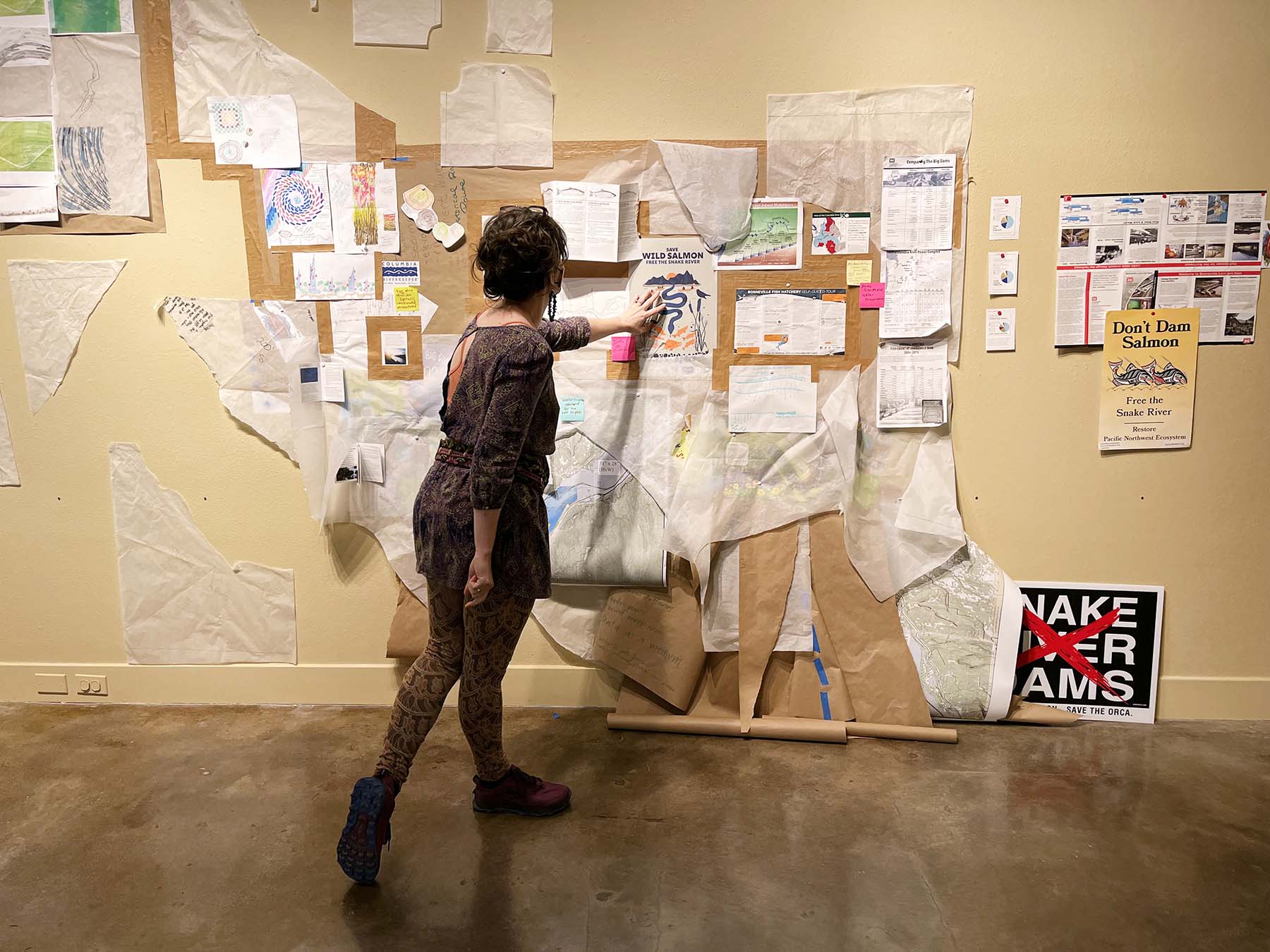

MAYBE IT WAS the state of wistfulness prompted by the fact that my 6-month project of interviewing the artists of the Exquisite Gorge II project is soon coming to an end. Maybe it had to do with entering yet another world new to me, a world filled with appliqué stitching joined with ceramics. What claimed my focus, intellectually and emotionally, was the idea of transitions. Good thing, too, since it is one of the reference points of Carolyn Hazel Drake‘s artistic vision. In dual ways, no less: the meaning of transition is conceptually expressed in her work, but exceptional attention is also given to the transitional points that connect the many small pieces in her larger installation.

Maryhill Museum’s Exquisite Gorge II project links multiple sections of the Columbia river, represented by as many artists, to each other, forming a giant sculpture made out of individual artworks. Drake’s section 6 covers the stretch of the river that ranges from the Deschutes River to the John Day River, including The Dalles Dam, one of four dams built along this stretch of the Columbia between the 1930s and 1970s that displaced Native American communities and wiped out traditional fishing grounds. Celilo Falls, called Wyam, “echo of falling water” or “sound of water upon the rocks,” in several native languages, had existed for 15.000 years, the river providing salmon, the staple diets for the Tribes, the land a place to live, gather and worship. The historical, political and environmental implications of the erection of the dam and the destruction it wrecked, were enormous.

“HOW DO YOU TELL A STORY that is not necessarily your own? How do you capture a landscape that did not always belong to you? How do you document reality without appropriating someone else’s history? These questions pose themselves to any artist, anthropologist, historian who is aware of the limitations of their own perspectives.” I had written these words in relation to Section 6 when interviewing the assigned non-Native artist for the first Exquisite Gorge Project 3 years ago. They apply now as much as then. Carolyn Hazel Drake gloriously rises to the challenge just as Roger Preet did in 2019.

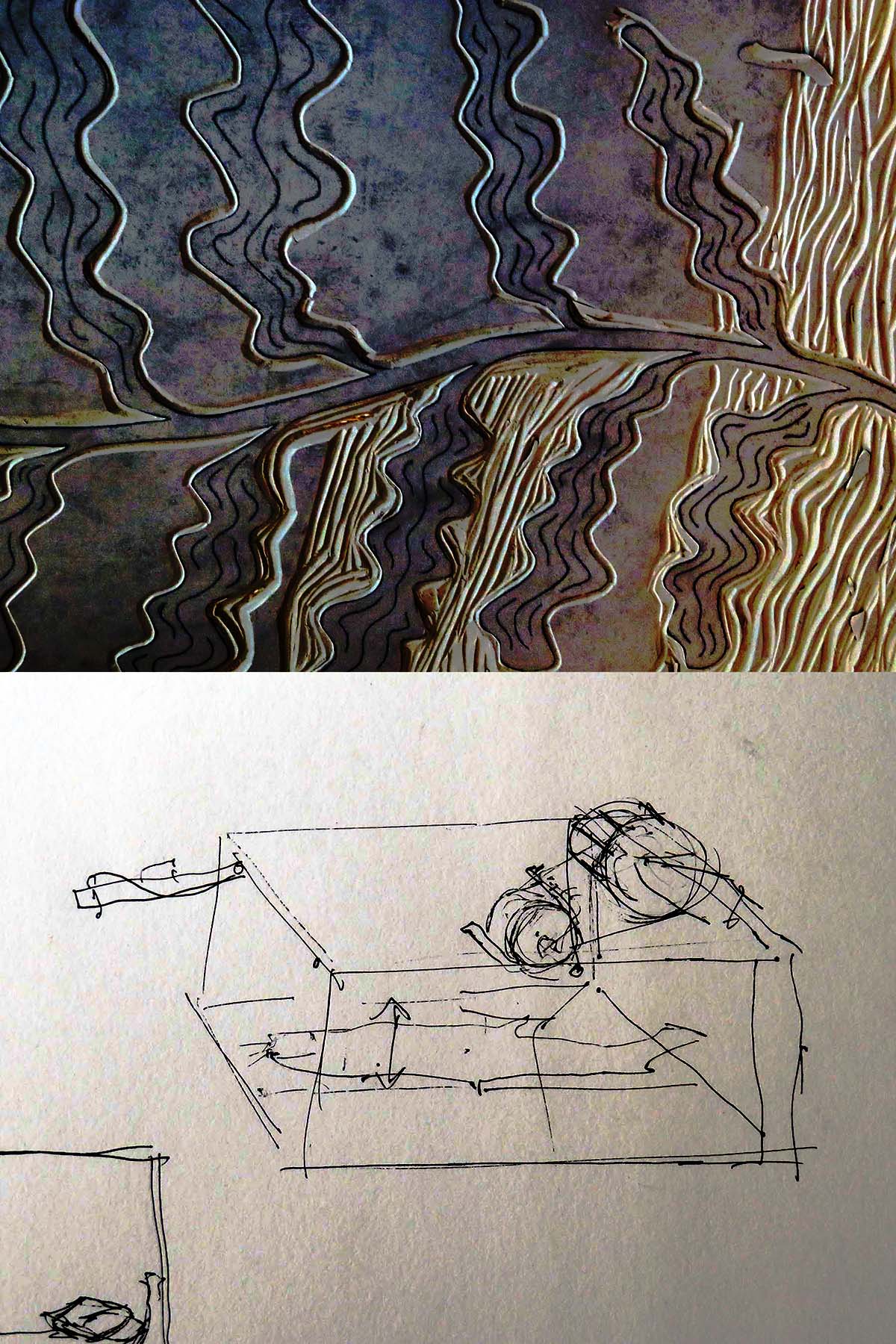

The story that she tells reflects the transitory nature of the river, constricted by dams, the flow that is constrained or enhanced by external forces, the bi-directional migration of the birds that come and go, always in transition. The beauty of the landscape’s colors is captured in a muted scheme that matches the solemnity of remembering the losses of the Tribes, incurred by forced relocation. It is about the river, its fate as well as its strength, the despair imposed on those who call(ed) it home and the resilience that nature confers.

MUCH RESEARCH, both on site and in the literature, preceded the design. Exploration of palette, gathering of materials, choice of fabric to go into a “river” of linked/divided pieces covered with abstract representations of the flight of geese, and lined by ceramic “stones” representing the river banks.

The geese come and go, helping the eye to move along the river, just as they would when observing them in nature.

The stones sway softly, as will the river as a whole when suspended and moved by the wind in the outdoor installation at Maryhill Museum. The somber tones are offset by an occasional striking burst of color. Drake uses Japanese Daiwabo fabrics, yarn-dyed before woven, with nuanced variations. Some are neutral, some muted and some are toned-down, reminiscent of traditional Japanese colors like gray willow (yanagi-nezumi), color of old bamboo (oitake-iro), or time altered celadon (sabi-seiji), leaves in autumn (kuchiba)and the color of water (mizu-iro / suishoku/).

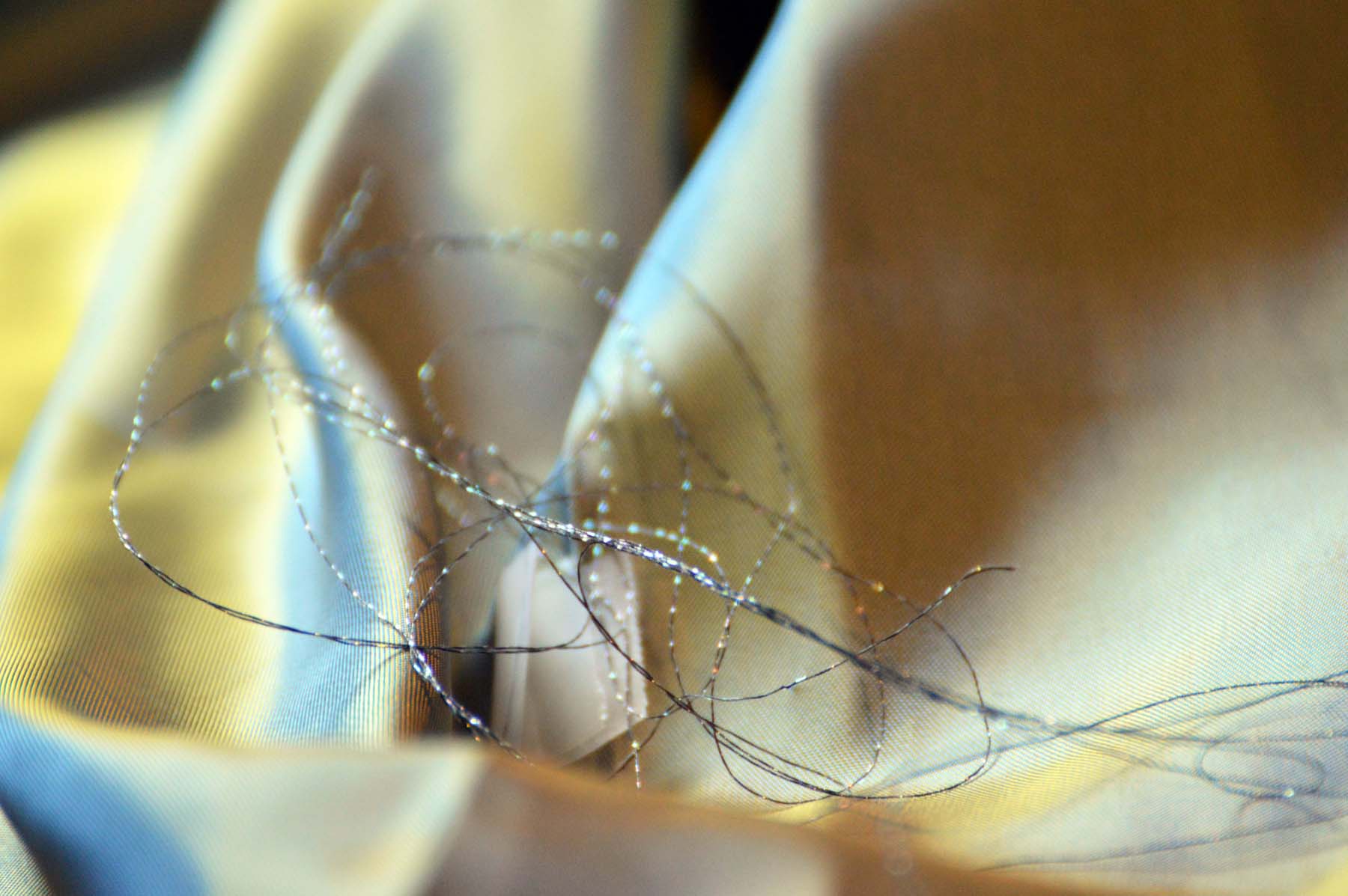

When examining the thought and craft going into the detail work, all I could think of was: Patience, precision and particularity. The dividers of the panels, for example, are sewn into wool fabric that is used to line the woolen blankets produced by Pendelton. Pendelton Woolen Mills has had a longstanding relationship with PNW Tribes since its incorporation in 1909; their first blanket designer, Joe Rawnsley, appropriated tribal preferences for elements in their blankets. The tribal blankets were constructed then as now in the jacquard method, creating woven patterns in a textured woolen fabric. Today they make custom blankets, (not for public sale) “given to honor events on life’s journey: birth, marriage, coming of age, graduation and even death, as well as special celebrations and gifts.” One annual special blanket is created in order to fundraise for the American Indian College Fund. Blankets are produced in Pendelton, but the finishing work is done in Washougal, WA, right at the banks of the Columbia river.

The hand-stitching of the appliquéd work is beyond regular, requiring the patience of a saint.

The knotting of the bands of “stone” is tight and precise with cotton-string dipped into bee’s wax.

The frame was special-ordered by the artist, with wood matched in color to the fabric installation, blending in with shades of muted green.

New frame on left – the provided one next to it.

I cannot begin to imagine what it took to apply the thousands of small dots, with slight color gradations, with a micro-tipped ink bottle after the porcelain beads were made and glazed. As always when I find myself in serene spaces – and Drake’s studio is bathed in serenity, light, orderliness, simplicity and all – my imagination was allowed to run free, absorbing what was in front of me, rather than being distracted.

The many tiny dots danced in front of my eye, grains of sand from the Columbia shores, salmon roe, tears from the trail(s) of tears, even the shorter local trails after Celilo Falls was destroyed, the flocks of geese that disappear into the distance on their migratory journeys. You choose. Then again, why choose at all. Varied reminders of a landscape and its history might be exactly what we need. Each finding a place in the family of things.

Canada Geese I photographed in January

***

lim·i·nal

1. relating to a transitional or initial stage of a process.

2. occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold. – Oxford Language Dictionary

CAROLYN HAZEL DRAKE is a third generation Oregon who acquired her affinity to fabric early on in her mother’s quilting store. She received her BA in English Literature, with a minor in Architecture, and her MA in Education from Portland State University, the first in her family to graduate from College. She taught language arts and art history in Portland’s Public School System for more than ten year and was also a PPS Visual & Performing Arts Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA); come fall, she will be teaching art at Arizona State University. Also in the fall, she will be artist in residence for two month at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology. In case you’d wondered how one pulls off a double load, rest assured: she has experience with that! If you look at the number of previous residencies and her role as a member of the Portland Art Museum’s Teacher Advisory Council all successfully integrated with her professional obligations, there is no doubt she will thrive.

The dog and I are, of course, exhausted just thinking about it.

In addition to working with fabric, Drake is nowadays exploring ceramics, particularly smoke firing techniques, and much of her recent work has combined the two in novel ways. One of the things that fascinates her about porcelain or clay is the porous nature of these materials, a mode that allows transition. She is fascinated by liminal spaces, and not just the ones in the geographical world.

Liminal comes from the Latin word ‘limen’, referring to ‘threshold’ or ‘doorway’. Liminal is that which occupies the transitional space at a boundary or threshold, a river being a perfect example of a gateway to new or different locations. Hallways, bridges and crossroads are other geographical locations that link a point of departure with a destination. Liminality is not restricted to a geographic place, though. There can be liminal time, the border between day and night during twilight, for example, or between the old and the new year. Liminal space can also be a cognitive or experiential dimension during times of transitions, when we experience major change, or go through periods of uncertainty. In many religious ceremonies that employ rites of passage, a liminal point is reached in the middle of the ceremony defining a before and after.

I HAD BEEN THINKING about liminal space in a completely different context before I even visited with the artist. There is a fascinating, if strange, development of Artificial Intelligence programs like DALL-E that allow the creation of images from text, having been trained as a neural network with everything art history has to offer – and then some.

“…it has a diverse set of capabilities, including creating anthropomorphized versions of animals and objects, combining unrelated concepts in plausible ways, rendering text, and applying transformations to existing images.”

Let’s say you request a painting of Black men drinking coffee in the snow, in the manner of John Singer Sargent. You utter the words and you get this. Made by a machine. (Well, I got it from reports by Brandon Taylor, a perceptive and witty author whose book Real Life was an impressive debut and who has been playing around with the AI program, posting diverse results.)

Or you ask for a Sargent version of James I and the Duke of Buckingham as a couple.

Or here is a machine generated portrait of the Duke of Navarro by Edward Hopper.

I’m bringing this up because the borderline between AI creations and art made by the rest of us will become more and more porous, it’s early days yet. I am not interested in a discussion of what is “real” art, or if we can ever tell a fake from a human original in years to come, or any such topic. (Nor am I interested in losing more sleep over potential dangers of perfected AI programs – if you dare you can read a basic AI 101 horror tutorial here…)

I am interested in how transitions will unfold between what we embrace and what we reject, and if there are aspects of human creativity that simply cannot be mimicked no matter how many neural nets draw on data from infinite exposure to all of our knowledge sources. Or can they?

Take Drake’s interest in liminal constructs. She plans to use her Sitka residency to create urns and altar cloths, combining, if possible, ceramic and fabric art for both. Urns stand for the remnants of someone who has walked on, transitioning into an unknown place (if you are spiritual,) or into dust (old secular me.) They remind us of humans’ transitory nature, or, by the care that someone takes to create beauty across their surface, that we will keep a memory alive, waiting for the pain of loss to recede.

Altar cloths are used during worship, also devoted to something we cannot fully know, but in whom we invest hope for allowing a transition into a better place. They cover the chalice that carries the Holy elements and the altar itself – should a drop of wine believed to be Jesus’ blood be spilled it will be caught by that cloth, not touching the altar itself. (Ref.)

What I cannot begin to imagine how something so thoroughly, deeply human can be incorporated into AI art. But maybe it can – maybe the sense of unease that is so often associated with liminal places, caves, chasm, empty airports at night, you name it, will find justification when AI turns out to be a match.

In the meantime, we have the quiet beauty and search for meaning that is deeply incorporated into Drake’s art. As real and as resilient as the river landscape that she has sought to depict. No further transitions needed. It is a place to rest.

————————————————————————

THE EXQUISITE GORGE PROJECT II

“…a collaborative fiber arts project featuring 13 artists working with communities along a 220-mile stretch of the Columbia River from the Willamette River confluence to the Snake River confluence. The project, again initiated by Maryhill Museum of Art and following the original one by printmakers in 2019, takes inspiration from the Surrealist art practice known as exquisite corpse. In the most well-known exquisite corpse drawing game, participants took turns creating sections of a body on a piece of paper folded to hide each successive contribution. When unfolded, the whole body is revealed. In the case of The Exquisite Gorge Project II, the Columbia River will become the ‘body’ that unifies the collaboration between artists and communities, revealing a flowing 66-foot work that tells 10 conceptual stories of the Columbia River and its people.”

Artists and Community Partners:

Section One: Oregon Society of Artists–Artist: Lynn Deal

Section Two: Lewis and Clark University–Artist: Amanda Triplett

Section Three: Columbia Center for the Arts, The History Museum of Hood River County and Arts in Education of the Gorge–Artist: Chloë Hight

Section Four: White Salmon Arts Council and Fort Vancouver Regional Library–Artist: Xavier Griffith

Section Five: The Dalles Arts Center and The Dalles-Wasco County Library–Artists: Francisco and Laura Bautista

Section Six: The Fort Vancouver Regional Library at Goldendale Community Library–Artist: Carolyn Hazel Drake

Section Seven: The American-Romanian Cultural Society and Maryhill Museum of Art–Artist: Magda Nica

Section Eight: Desert Fiber Arts & REACH Museum–Artist: Ophir El-Boher

Section Nine: The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation–Artist: Bonnie Meltzer

Section Ten: ArtWalla–Artist: Kristy Kún

Frontispiece: Tammy Jo Wilson and Owen Premore