German is known for its compound words, the joining of two words that then create a new meaning, some of which have gained enough of a reputation to be understood by readers who primarily speak English. Schadenfreude, joy in other people’s misfortune, might be one such, as is Weltschmerz, the heartache over the world’s woes, or your own, for that matter.

I have different favorites, all connected to my own person, Weichei among them, literally a soft egg, but referring to one decidedly wimpy. Then there is the innere Schweinehund, literally an internal pig dog, which refers to one’s weakness of willpower. (Not to be mistaken for Schweinehund, pig dog, which refers to a particularly mean villain. Deutsche Sprache….) Let’s add the Tagedieb, the day thief, who dawdles away her time, that lazy layabout, and Eselsbrücke, the donkey bridge, a name for mnemonic devices, those memory aides which have become indispensable for this aging brain.

One of the joys of reading poetry in your own language is the discovery of compound words that do not exist in the extant language. There is a real thrill when these inventions make perfect sense or suggest something that is new but obvious, or create a hook for you to think about language as it should be but has never seemingly come about. They are also often creating an uncanny mood for their simultaneous familiarity and unfamiliarity.

These invented compound words are also a nightmare for the translator, and a struggle for the second-language reader, since they would not know what is established and what is designed vocabulary.

Luckily, one of the masters of German 20th century poetry, Paul Celan, had some of the best translators one could wish for, John Felstiner, and more recently Pierre Joris, who spent 50 years to convey the entirety of Celan’s works. (The newest edition is Memory Rose into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry. And here is a long but informative interview with Joris about his translation work.)

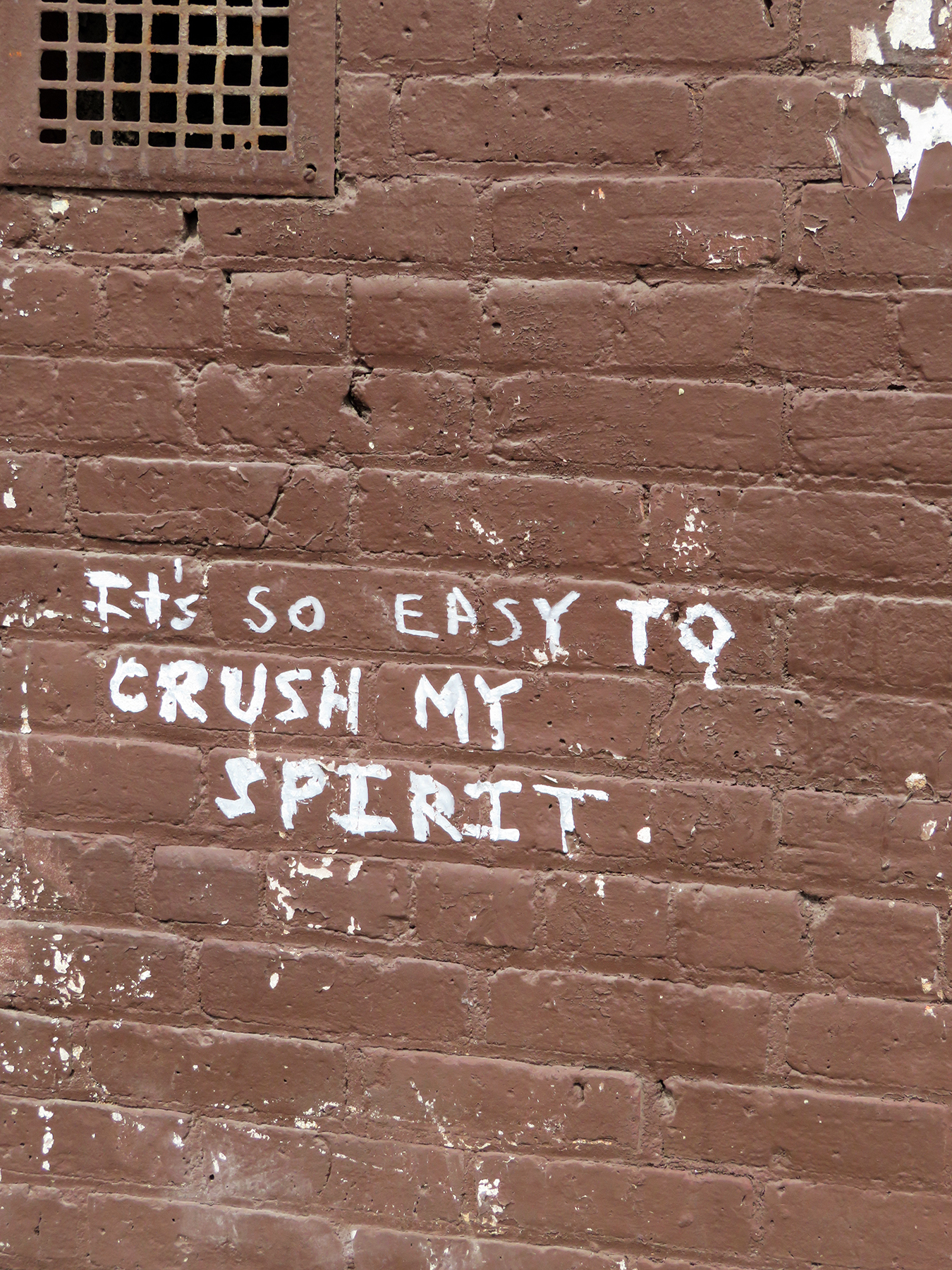

Even they, though, might not quite capture what a native speaker intuits: Take Celan’s creation Sprachgitter, for example, translated as speechgrille. Gitter are primarily used in German to refer to prison bars. Bars keep you in. Bars can also keep others out. A languagebar or speechbar is obviously not a good translation since it would sound like an obstacle. But the sense of language as a force that prevents departure or entry, a separation device, is not exactly embodied in grille, which rather suggests permeability.

These difficulties aside, it is remarkable that a poet who survived the Holocaust (his entire family did not) sticks to the language of the murderers, admittedly also the language of his mother, even though he is fluent in many other languages.

More importantly, the poet was aware of the abuse of the German language by the totalitarian perpetrators. He called it murderous speech.

“Only one thing remained reachable, close, and secure amid all the losses,” he later said of his experiences in the camps: “language. Yes, language. In spite of everything, it remained secure against loss.” “But,” he added, “it had to go through its own lack of answers, through terrifying silence, through the thousand darknesses of murderous speech.” (More on this here and here.)

The ideological core message of supremacists, as we discussed earlier, is one of separation: us vs. them, the good against the bad, the nation against the enemy, the White against the Black, the Nazi against the Jew. Celan’s language systematically undermines separation by fusing words together, words that never belonged in a pair, the compounds creating an ambivalence that stands in direct opposition to the absolutist value and expression of murderous speech. His new words allow us, on occasion, to cross the threshold of separation joining something new.

What is a memoryrose?

What is breathturn, what is timestead?

What is ashglory in the context of the Holocaust? Have to read the poems!

Here is Celan reading his own work, translation in subtitles.

Music composed for three of his poems, here.

Photographs are from Paris where Celan lived until his suicide at age 50 in 1970.

Bonus: Here is an excerpt from Jewish Currents that analyzes one of my favorite poems (a stanza, really) as the professionals do…. I just liked the imagery placed into my hometown, otherwise had no clue.