The Berlin Requiem – Red Rosa.

· Beyond the Tree Line ·

“Die rote Rosa nun auch verschwand / Wo sie liegt, ist unbekannt / Weil sie den Armen die Wahrheit gesagt / Haben sie die Reichen aus der Welt gejagt.” – Bertolt Brecht, Epitaph to Berlin Requiem.

I think I reported on this here before, some years back, but the memory repeatedly pops up. On my 11th birthday I received a book with the title Famous Women in History, or some such. Probably meant to be inspirational, or teaching history through human interest stories – but I bet the bank my parents never read a line of it, otherwise they would have reconsidered. The heavy tome included an accumulation of bloody fates, either executed by powerful women, or experienced by powerful women, or both.

There was Judith (dead Holofernes, a head shorter), Cleopatra (dead Antony, falling on his sword, dead queen, self-poisoned), Queen Boudica (80.000 dead Roman legionaries, dead queen by suicide), Jeanne d’Arc (a lot of dead soldiers, a martyr burnt at the stake), Queen Mary I. a.k.a Bloody Mary, (beheaded competitor, Lady Jane Grey, countless executed protestants), Charlotte Corday (dead Marat in the bathtub, guillotined Charlotte), Marie Antoinette (off with her head), Catherine the Great (murdered husband, Peter III, innumerable dead after she extended and harshened serf conditions from Russia into Ukraine,) Typhoid Mary (dead everybody) and so on. One notable exception, and the only scientist mentioned: Mme Curie (dead by radiation exposure.) You would think famous women were all naturally born killers.

I have, of course, no clue how accurate and complete my memory is for a book likely written in the 1940s or early 50s, if not earlier. The book itself is long lost during my many moves in the ensuing decades. Maybe only the horror examples stuck, and I forgot the chapters about happy princesses, humanitarian nuns, or outstanding female artists. Maybe the selection of prominent bloody endings was intended to instill fear of power into impressionable little girls, keeping them in their place. Or maybe it just happens to be historically accurate that the few women who made it into the history books had, indeed, to be ruthless to join the ranks of male rulers, religious zealots, (anti)colonial fighters and tyrants.

I do know, though, who was not included, because I was introduced to the name only when my interest in politics awakened: a female intellectual and revolutionary who left a mark on her world and/or the future. She’d fit the pattern: a woman who supported an uprising, murdered in the most heinous way, her mutilated body dumped into Berlin’s Landwehr Canal: Rosa Luxemburg. (Her comrade Karl Liebknecht, who was executed the same day, was granted a funeral, because he was not Jewish. Käthe Kollwitz was asked by his family to visit the morgue and created one of her most famous memorials.)

Luxemburg, one of the first women to receive a doctorate in law and economics, a brilliant philosopher and fighter for justice, has been on my mind because we have been hearing the word Freedom brandished about in the election campaign. One of her most famous quotes (criticizing the new Russian regime, no less, in a book written in 1918 and published in 1922, The Russian Revolution,) was this:

“Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently. Not because of any fanatical concept of ‘justice’ but because all that is instructive, wholesome and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effectiveness vanishes when ‘freedom’ becomes a special privilege.”

Also on my mind has been the fact that she and Liebknecht were killed by soldiers from the so called Freikorps, a group composed of former officers, demobilized soldiers, military adventurers, fanatical nationalists and unemployed youths hired by right-wing extremist von Schleicher, a staff member for President Paul von Hindenburg (who later appointed Hitler as chancellor.) The Freikorps was explicitly founded to fight left-wing political groups and Jews, deemed responsible for for Germany’s problems, and pursued elimination of “traitors to the Fatherland”.

“The Freikorps appealed to thousands of officers who identified with the upper class and had nothing to gain from the revolution. There were also a number of privileged and highly trained troops, known as stormtroopers, who had not suffered from the same rigours of discipline, hardship and bad food as the mass of the army: “They were bound together by an array of privileges on the one hand, and a fighting camaraderie on the other. They stood to lose all this if demobilised – and leapt at the chance to gain a living by fighting the reds.” (Ref.)

I don’t have to explain why images of violent losers and wanna-be heroes ready to incite bloodshed are on my mind. Never underestimate the danger from a militia.

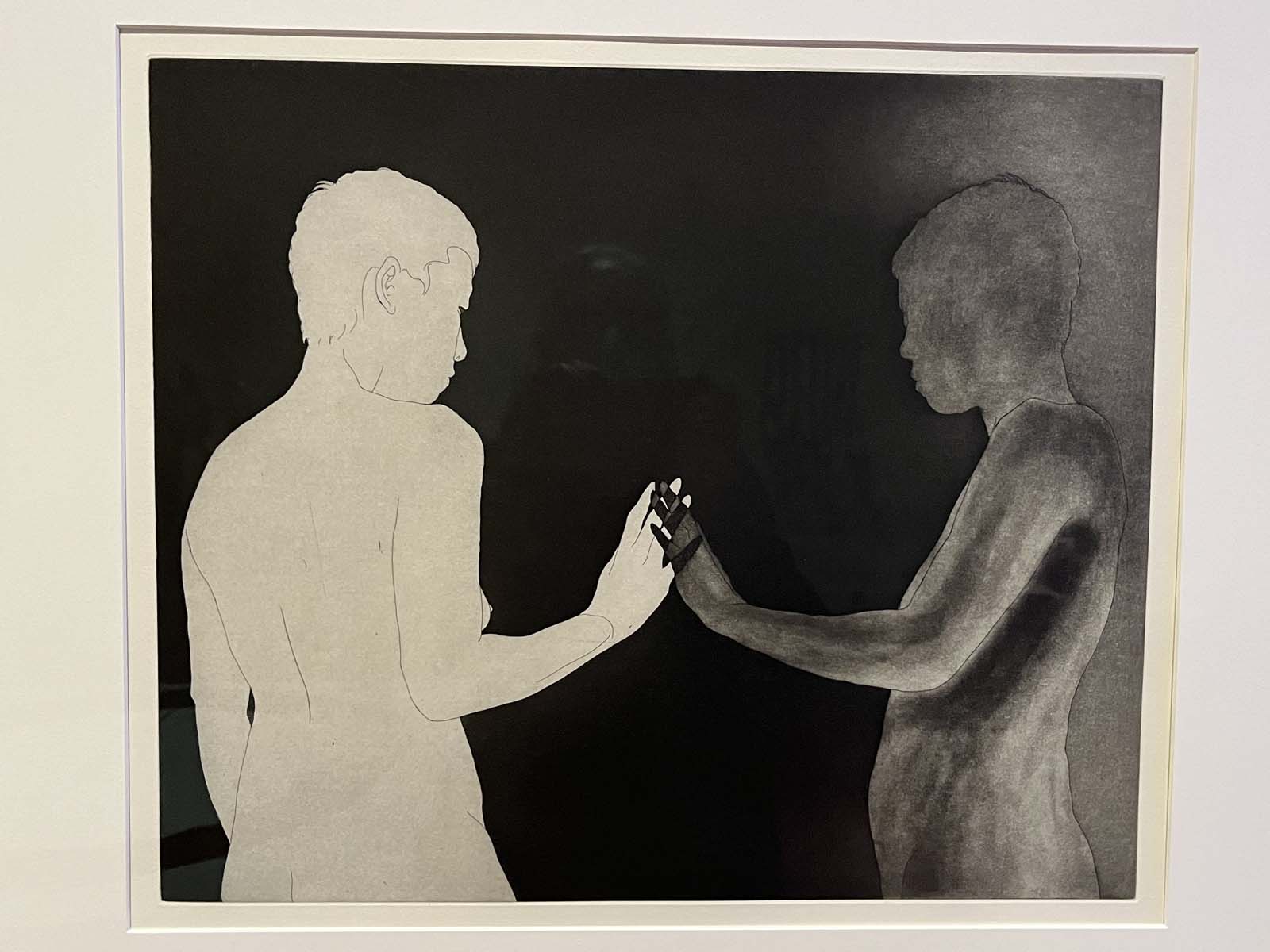

The montage is trying to reflect Kurt Weill’s 1928 composition The Berlin Requiem. Weill included Bertolt Brecht’s poetic memorial Epitaph upon Luxemburg’s death: “Red Rosa now has vanished too…. / She told the poor what life is about, / And so the rich have rubbed her out. / May she rest in peace.” (The second movement.)

I chose a wide path bordered by crooked trees to celebrate a woman’s courage to leave the straight and narrow one proscribed, pursuing an ideal of radical democracy instead, her thinking opening windows into a brighter world. She reached high in her pursuit of social justice and freedom for all, just like these trees are reaching for the light, defying the storms that bend them. They were photographed in Holland at the North Sea, but same can be found in coastal Poland, the country where she was born.

Here is the Requiem.