Double dipping today – this will be up at Oregon Arts Watch as well.

IT HAPPENED TO ME AGAIN. That’s twice now, in just two years. I had to revise my assessment of an artist once I got to know the history and environment that was essential to their work. The first re-evaluation took place both on an intellectual and an emotional level – where I truly disliked Frida Kahlo before, I came round. https://www.heuermontage.com/?p=5790

And now I have to admit something similar is happening for Georgia O’Keeffe. I was never a fan of the endlessly repeated desert skulls or foreshortened flower paintings, imbued with sexual metaphors or gender-specific markers – references, it turns out, mostly peddled by the men in her life in the beginning of her career and appropriated by many a feminist at some later point. O’Keeffe herself rejected these interpretations just as much as being co-opted by the feminist cause. (For a thorough analysis of her relationship to feminism read Linda M. Grasso: Equal under the Sky: Georgia O’Keeffe & Twentieth-Century Feminism University of New Mexico Press, 2017)

I was also not particularly taken by the way the oil paintings were rendered. Even though the landscapes use saturated colors, there is often a dullness that does not capture the intense brightness of New Mexico’s high desert. Laura Cumming, reviewing the 2016 O’Keeffe retrospective mounted at the Tate Modern, says it better than I possibly could:

But by now, what strikes is the stark disparity between the sensuous imagery and the dust-dead surface. O’Keeffe’s oil paintings turn out to be pasty, matte, evenly layered. They have no touch, no relish for paint, no interest in textural distinction. They are as graphic and flat as the millions of posters they have spawned worldwide; in fact, on the strength of this first major show outside America, they look just as good, if not better, in reproduction. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/jul/10/georgia-okeefe-review-tate-modern-retrospective

Mostly I was put off, though, by her ways of perfecting a persona, here too some semblance to Kahlo. She paid a lot of attention to how she looked (perhaps to be expected in one so often photographed) down to having a beloved piece of jewelry recreated in a different metal that better matched the color of her now white hair. She insisted on – often self styled – black and white clothing when being photographed, although she appeared usually in quite colorful clothes. The environments she lived in, particularly later in life when fame also brought fortune, were carefully arranged with designer furniture – Mies van der Rohe and Saarinen pieces among them. It is unsurprising that we now have traveling exhibits dedicated to her style, her clothes, her surroundings. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/touring/georgia_okeeffe_living_modern

And above all there was that myth making of the independent, strong, lonely recluse seeking solitude in the acrid Southwest after life got too complicated on the East Coast. I had trouble squaring my images of recluses with someone having a house keeper, a gardener, a staff, and a coterie of friends, neighbors and endless groupies while floating on ever growing fame as a true American modernist. She objected to be associated with anything commercial (allusions to the fact that some of her paintings foreshadowed pop art infuriated her) but her ascent was driven, in part, by the commercial aptitude of her husband, photographer, artist and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz, a much older man.

•

SO WHAT SHIFTED? Why have I started to see the artist and her art with new eyes and a certain appreciation? It was a combination of three factors during my recent visit to Santa Fe. I saw her early work in the lovely museum dedicated to her (https://www.okeeffemuseum.org).

I watched a documentary movie that the museum offers, in which the artist ruminates on her own life, and I experienced the landscape of New Mexico for the first time.

The museum offered the usual biographic time line. Born in 1887 to farmers in Wisconsin, O’Keeffe teaches school in rural Texas after training at the Art Institute in Chicago. She takes up with Stieglitz, a leading promoter of modern art, and becomes part of an influential intellectual circle that catapults American art out of the dark ages, including names now extremely familiar to us, among them “Make it new!” Ezra Pound and “The Local is the Universal!” William Carlos Williams. She is close friends with another photographer and protégé of Stieglitz, Paul Strand, as well as his wife Rebecca and later Ansel Adams and Todd Webb. When her husband turns to even younger women and their marriage falls apart she moves to the Southwest, having visited every summer previously for many, many years.

All that I knew. I now learned, that this path was also riddled with disease and breakdowns (psychiatric wards included,) not as extreme as that of her friend Frida’s, but enough to stress how strong she must have been to go her independent ways. I was also drawn in when she talks about happiness in the documentary. She said something along the lines that happiness is insubstantial and short-lived for most people. What counts is being interested and that she was. She also took, she insisted, throughout life what she wanted.

•

INTERESTED SHE WAS: it shows in her ways of learning and applying principles developed by other artists – and then giving those principles her own rendering, taking what she wanted, whether that meant sticking to abstraction, or emulating strands of Neue Sachlichkeit. Being able to see her early abstractions, not painted in oil, made that particularly clear to me. These lovely watercolors herald later form and point the way to her insistence on 2-dimensionality, even in her landscapes.

Interest helped her to extract what she could use from all these photographers around her: endlessly modeling for Stieglitz, Strand, Adams and later Webb did not stop her from taking from this art form what made her paintings part of the American Avant-garde: she zoomed in and out in her depictions, as if she had those different lenses, shifting from macro to wide-angle renderings, making things big that were small and vice versa. Lessons of scale drawn from photography clearly influence her during most of her career.

(And talking about photography – it drives me to distraction that every exhibit of her work that I have ever seen or read about, is paired with photographs of her by all these famous men in her life. It really has the viewer focus on her as a subject rather than her as the agent of her art.) But she took what she wanted: she left when it suited her, she stood by her artistic vision even when pressed to adapt to that of those around her and she experimented with relationships at a time where it took even more courage than it does today.

Interest made her a world traveler – particularly later in life when she went all over the place, always to return to her home in New Mexico where she finally settled in 1949, three years after Stieglitz’ death. And this landscape, as I now understand having seen it, provides a superb match to anyone with photographic sensibility. The thin air and the way it affects vision upends our usual ability to judge distance; in this way her paintings are quite literal depictions, only intensified by her proclivity towards abstraction. It is also a landscape in which anything incidental disappears when trying to brave the harsh elements, the dryness, wind, dust, heat or cold. That, too, is captured in O’Keeffe’s work, with its singular focus.

The ground she walked and worked on in NM consists of compressed material from volcanic eruptions called Tuff. It is a soft substance, crumbly, easily destroyed – everything the artist was not, even though she had to endure one of the worst nightmares imaginable for a visual artist: macular degeneration. It appeared first in 1964, and her last unassisted oil painting was finished in 1974. She died in 1986, 98 years old. She might have been self-absorbed, vain, single-minded, but she also was vulnerable, thoughtful and above all, tough. Can’t help but like that, and allowing it to color the assessment of her art.

•

INTERESTED SHE WAS AND INTERESTING SHE REMAINS. If you are curious to learn more about O’Keeffe, here is your chance: The Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust education presents Carolyn Burke on Tuesday, 4/30 at noon. The renowned author will discuss her book, Foursome: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand, Rebecca Salsbury.

http://www.ojmche.org/events/2019-brown-bag-with-carolyn-burke

And if you are lucky, you will have a chance to listen to a new opera about O’Keeffe wherever it will next be produced. Today it rains with music by Laura Kaminsky and a libretto by Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed just saw its world premiere in San Francis late March. It is staged as a train ride that O’Keeffe and Rebecca Strand take to NM, where they play drunken games and talk about their lives. https://operaparallele.org/today-it-rains-2/

The only musical excerpt I could find is late in this clip, start at 25:00: And yes, it’s modern chamber opera. You know what that means.

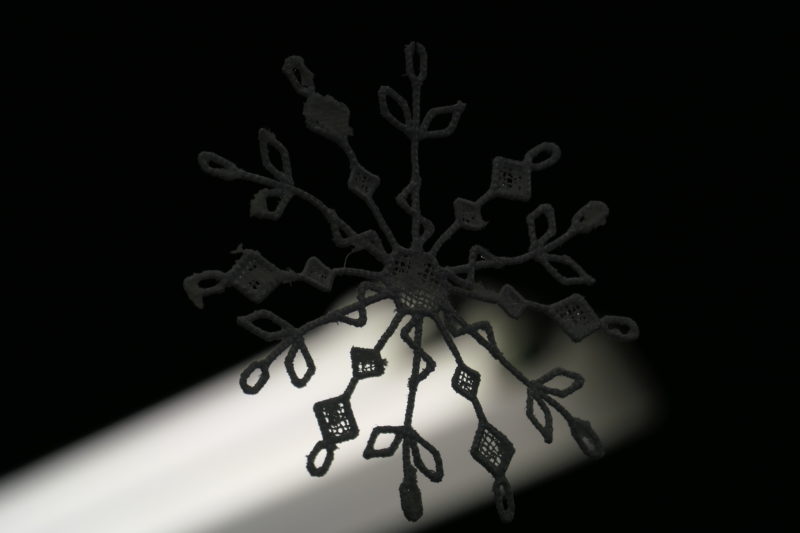

Photographs today were taken completely independently of the paintings in NM and only later matched up. Talk about translations of a landscape….