“Guns symbolize the power of a minority over the majority, and they’ve become the icons of a party that has become a cult seeking minority power through the stripping away of voting rights and persecution of women, immigrants, black people, queer people, trans people – all of whom have been targeted by mass shootings in recent years.” –Rebecca Solnit

Agnotology is another word I had to look up in the dictionary. It refers to the study of ignorance, and the ways in which ignorance can be the outcome of acts of interference with your learning. Ignorance, then, not just as the absence of knowledge, but the product of cultural or political processes designed to prevent you from knowing.

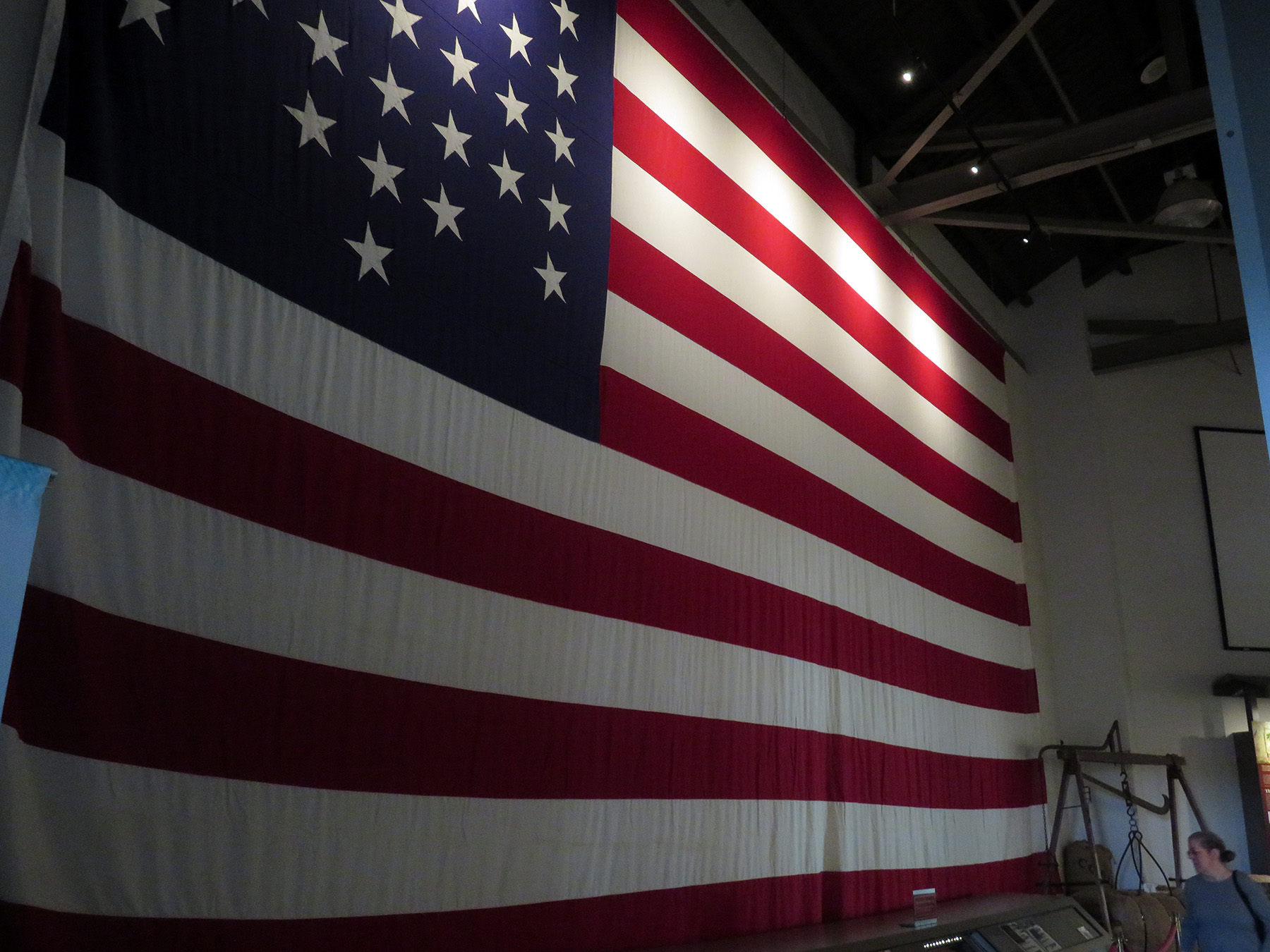

(Photographs today are from the museum at Fort Sumter, the site of the start of the American Civil War, and graves of the fallen in Charleston, South Carolina, mostly decked with confederate flags and visited by birds.) I approached the monument by boat a few years back.

AGNOTOLOGY, The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, a 2008 classic text edited by Stanford profs Robert Proctor and Londa Schiebinger, both historians of science, is worth revisiting in the context of the 2nd Amendment debate.

According to Proctor the “cultural production of ignorance” has been instrumental for the tobacco and fossil fuel industries. It is now embraced by the gun lobby as well. (I am summarizing what I learned here.)

Think of things that can make you sick: tobacco, sugary foods, chemicals applied for agricultural use, poisoning ground water, to name just a few. The industries peddling these commodities are focused on certain propaganda. You can cast doubt on the scientific linkage between cigarettes and cancer, for example. You can shield producers and sellers from scrutiny. And you can shift the debate to issues of “personal responsibility.” Same for things that sicken the planet: you can cast doubt on the relationship between fossil fuel use and climate change, protect the oil industry from scrutiny, and shift responsibility to the consumer, rather than reveal structural policies that harm.

With regard to guns that kill: you can prevent research from being done (or revealed) that shows the true causes for gun violence, including objective measures of what freely available gun access implies. You can spare the industry any liability, and you can blame individual factors, like mental health, or loosening family structures, or grooming teachers, or sexual mores or video games – you name it, all with the goal to prevent policies that curb the unconstrained purchase of arms.

And last but not least, you can sell alternative “legal scholarship,” which eventually makes it upstream to the courts when interpreting 2nd Amendment origins and meanings.

Given the amount of misinformation, what DO we know about the history of gun laws? The first law prohibiting guns for certain people was enforced in Virginia in 1633. No guns for Native Americans. Other colonies followed suit. Enslavers, too, wasted no time (Source here):

As early as 1639, on the other hand, laws were requiring White men to be armed to be able to act as militias controlling the enslaved population.

Eventually the 2nd Amendment to the Constitution was written not to favor individual gun use but for the protection of these slave-controlling militias, so that no-one could disarm them and disadvantage the Southern, slave-holding states who needed their might.

Note the phrasing in the museum annotation (below images of slaves) above. “only a small percentage…” as if that makes it less egregious. The rest was sold into slavery in the Caribbean and Brazil, with North American interests in plantations fed there as well. And they brought sickness to the continent! How dare they?

Below the focus on the variability of slavery experiences almost suggest there were some conditions that weren’t as bad as others, and prosperity demanded it!

Fast forward to the 20th century. The NRA early on approved of legislation limiting access to certain weapons, like the National Firearm Act of 1934 and the Gun Control Act of 1968. Things changed, though, with the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement and the New Deal, expanding the powers of government and altering structural hierarchies of US society. Fierce backlash happened among those seeing their status threatened, and a push towards unfettered arming of men. In the 1990s we saw a growing militia (Christian white power) movement in response to Clinton’s gun laws. (Think Ruby Ridge, Idaho and Waco, Texas.) These extreme right wing forces subscribe to the “insurrection theory” of the 2nd Amendment, which says that the 2nd Amendment protects the unconditional right to bear arms for self-defense and to rebel against a tyrannical government. If and when a government turns oppressive, private citizens have a duty to take up arms against the government. The Proud Boys were just one division that put this into action, among other things, during the January 6th storming of the Capitol.

By 2007 the majority of justices on the Supreme Court had been appointed by presidents who were members of the NRA. In D.C. vs. Heller, Scalia argued that the 2nd Amendment protects an individual’s right to own guns (unconnected to a well-regulated militia), but vaguely implied that there were limits to the right, frustrating both gun control voices and the NRA folks who had never seen a limit they liked, as far as their own desires were concerned

If you can tolerate a style of writing that does not shy away from a somewhat excessive use of expletives, I highly recommend reading Elie Mystal’s Allow Me To Retort, an analysis of the Constitution in extremely accessible form, with insights into the 2nd Amendment in particular. It is a short, brilliant primer. Here is a review that captures everything I felt after finishing this book.

A radical change to the law is expected to be handed down by the Supreme Court this month, expanding 2nd Amendment rights. Here is is the Brennan Center for Justice‘s full analysis of what we will likely face. It is worth noting that once the door has been opened to prohibit the government from sensible regulations, as is expected here with regard to carrying guns, other regulative power might soon be taken away as well: environmental protection, public health requirements, work place safety, to name just a view.

It is no surprise, then, that the teaching of history as it unfolded, and of the conditions some try to maintain (most Americans want stricter gun laws), is anathema to those who want to turn the clock back, weapons in hand to meet a government that does not please them (after they meet their neighbors, who do not please them either given the neighbors’ quest for righting the injustices of a racially segregated society.) They do everything to obscure and obfuscate the knowledge that could empower true democratic policies and decision making and impact the sales of deadly military-style weapons and the ideological purposes they serve – agnotology in action. A Supreme Court undermining majority rule acts as the hand maid.