Today’s musings will be all over the map, geographically, emotionally and with regards to content that has preoccupied my brain for a while. It all leads back to Octavia E. Butler, a writer who I admire for her exquisite, creative world building, her focus on in/justice, and her ability to transcend genres. I am even more grateful for all of her modeling of what it means to have courage and persistence, to stick to goals defying racist, patriarchal, professionally closed systems, while skirting existential poverty and loneliness during formative years.

All over the map: Let’s start with Trieste, Italy. Why Trieste? I was somewhat condescendingly amused during my 2018 visit there to see flocks of fans follow the footsteps of their hero, James Joyce, who lived and wrote major works in Trieste for years. Selfies with his statue, tour lines in front of his lodgings, photographs of the multiple plaques conveniently placed by the Bureau of Tourism: Joyce walked over this bridge here! More than once!

Well, I was wrong, I’ve joined the multitudes and never should have sneered. Not pursuing Joyce, nor taking selfies, but I am now trying to walk along the paths of someone I wish I’d understand, taking in the neighborhoods and buildings that were part of her daily life, reading about her struggle, and visiting places that keep her memory alive.

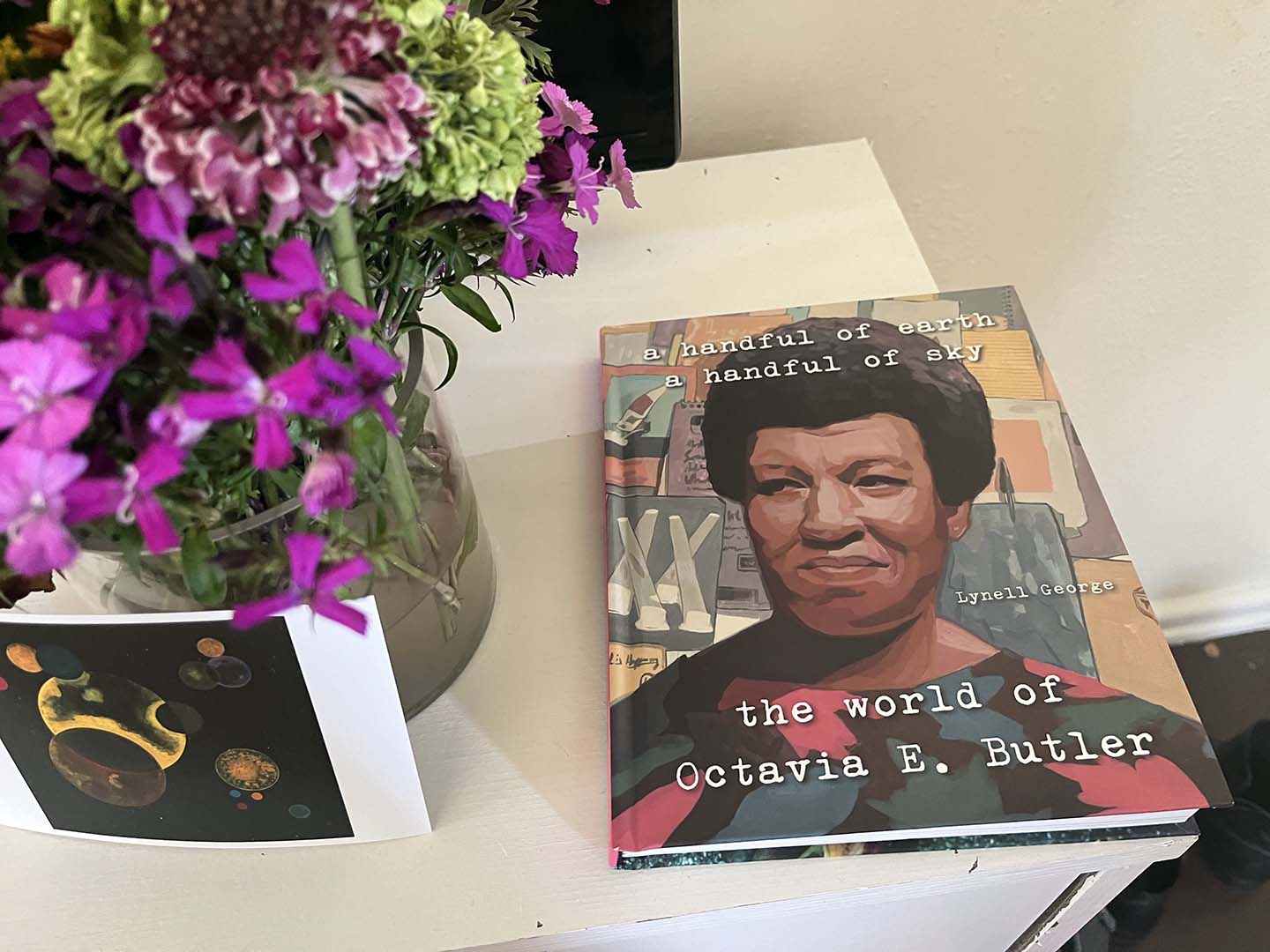

Pasadena, CA, then, is next. No plaques here, but a helpful map laying out routes frequently taken by Butler, prepared by people at the Huntington Library which holds the author’s archives. An even more helpful book by journalist Lynell George, A Handful of Earth, a Handful of Sky – the World of Octavia E. Butler, which introduces the canvas on which Butler drew both herself and the worlds she constructed from the insights captured by her daily struggles, the physical environment in which she labored, and the mental landscapes that she traveled while growing into the writer some of us now devour. George describes the author with exceptional sensitivity and intuition, during the years before Butler would go on to become a MacArthur (Genius) Fellow and win a Pen Lifetime Achievement Award, as well as Hugo and Nebula Awards for her trailblazing work in science fiction—the first Black woman to win both awards.

Butler was born in 1947 in Pasadena, CA, to a mother who worked as a maid and a father who was a shoe shiner and died when she was very young. She was dyslexic, isolated in school and not particularly supported by the majority of her teachers. Later she turned to menial jobs, often physical labor, that did not require much thought so she was free to do her own thinking, and could use the rest of her time to walk or visit libraries, some involving hours on the bus.

Historic center Pasadena, including the post office where checks, manuscripts acceptance or rejection letters might have arrived in her P.O.Box.

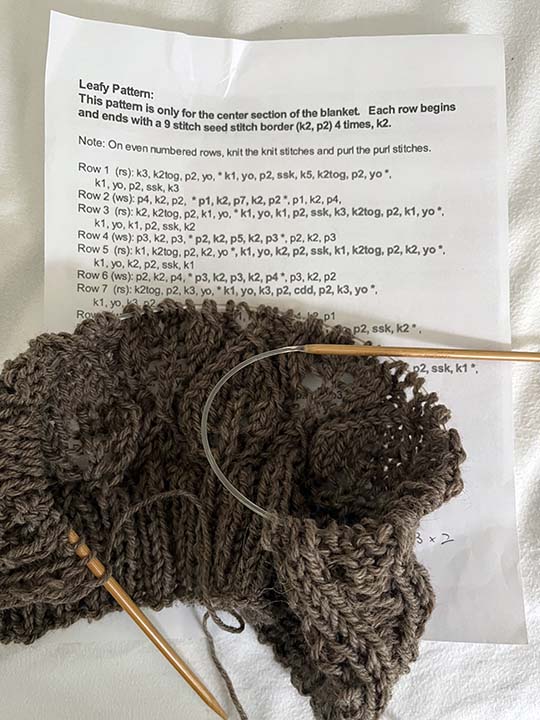

Lynell George’s account of these early years is, among other things, based on archival items that Butler saved over the years: lists. And lists. And lists. On scrap paper, or any other expandable surface she could write on, perhaps compulsively constructed to organize and likely ward off a flood of fears that might otherwise prove overwhelming. Shopping lists. To-do lists. Lists to evaluate what could be pawned to head off starvation. Lists of goals. Lists of dreams. Lists of exhortations or promises to Self, or incantations about how the world should be and how to make it so.

An eternally slow start to find her way into publishing, with 2 small manuscripts sold in 5 years, interminable stretches of professional drought, and yet this author went on to write and publish over a dozen books, with artists, play-writes, musicians and film makers increasingly inspired by the work since her death from injuries sustained in a fall at the age of 58 in 2006. Her novels are taught at colleges and universities around the country (well, where there are not yet banned, I should hasten to add…) and you can now watch adaptions of her books on TV. (Coincidentally, this weekend’s NYT listed an introduction to some of the essential works, so you can see for yourself how much ground was covered or where to start.)

***

Many of Butler’s books can be found in a small book store on North Hill Avenue in Pasadena, Octavia’s Bookshelf. It opened about a month ago and offers a range of works by BIPOC writers, and a welcome space to sit down and explore.

Here I meet Nikki High, owner of the store, who is helpful in recommending books when I approach her to pick her brain and perfectly happy to spend some of her valuable time chatting with this stranger. Which brings us to the Republic of Ghana, the west-African country where sociologist and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois resided during the last years of his life and is buried. He died on the eve of the civil-rights march in Washington,D.C., where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream”speech and where Roy Wilkins of the NAACP announced Du Bois’s death from the podium. I mention to Nikki that I am currently reading a thought provoking, beautiful novel by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, The Lovesongs of W.E.B. Du Bois, and she tells me about her recent travels to Ghana to visit Du Bois’ grave and the house he lived in, visibly moved by the reliving of that memory.

Jeffer’s novel revolves around the concept of Double Consciousness that Du Bois introduced in his seminal book The Souls of Black Folk (1903.) So does Kindred, (2003) Butler’s historical fiction/fantasy novel introducing a heroine who time travels between the 19th and 20th century, between the slave plantation where her ancestors suffered and her interracial marriage in 1976 L.A.. The novel has become a cornerstone of Black American literature.

Du Bois argued that living as an African American within a system of White racism leads to a kind of fragmented identity. The double consciousness refers to “the sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.”

“It is a socio-cultural construct rather than a baldly bio-racial given, attributed specifically to people of African descent in America. The “two-ness” of which it is a consciousness thus is not inherent, accidental, nor benign: the condition is presented here as both imposed and fraught with psychic danger.” (Ref.)

The socio-cultural existence is defined by a racial hierarchy that includes hostility and suspicion, subtle or outright exclusion, a life lived in uncertainty and guardedness. The individual’s identity, both novels argue, is also affected by the historical fact that harm extended beyond the individual to whole family structures and networks of kin. Only when you understand the legacy of historical trauma and merge it into your own sense of self will it cease to afflict you. Past and present need to be integrated to mend a disjointed self.

***

As luck would have it, the Octavia E. Butler Magnet School‘s library celebrates an OEB science fiction festival the next day. Previously Washington Middle School, the institution’s new name (since Fall 2022) honors its famous alumna. Since I have to avoid crowded indoor settings during the pandemic (it is NOT over, folks!), I cannot join the activities, but manage to get a few photos in a ventilated hallway. New generations are introduced to a role model that leaves you in awe for the obstacles overcome.

On to Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena, CA, where Butler is buried. It is a peaceful place with beautiful old tree growth, als long as you ignore the coyotes that they warn you about, patrolling in packs, by some reports.

Butler’s grave marker is unobtrusive, not easy to find. The inscription is one of her most frequently cited insights, from the book The Parabel of the Sower (1993), where she turned her attention to climate catastrophe and the subsequent militarization of state and rapidly shrinking chances of survival. Set in 2024, it seems utterly prescient in retrospect, its descriptions outlining the contours of our lived or soon to be lived reality.

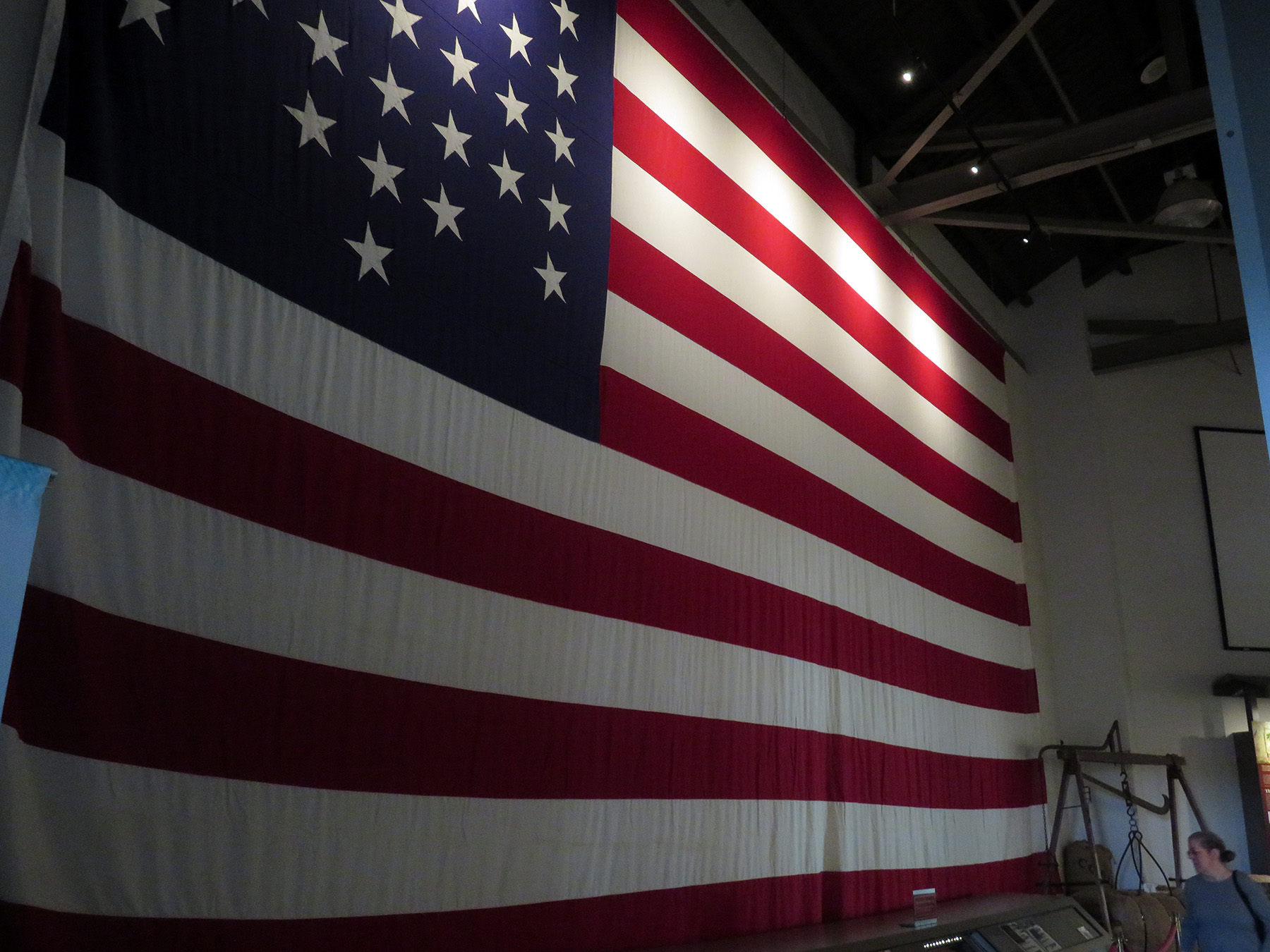

Allow me one short digression, and some speculation, you’ll see why in a minute. Butler’s last resting place sports numerous strange grave stones, if you can call it that, artificial tree stumps carved with the emblems of a maul, wedge, axe and dove, as well as markers inscribed with repeat phrases, the Latin motto “Dum Tacet Clamet” which translates to “though silent, he speaks.” A bit of research brought me to Omaha, Nebraska, where one Joseph Cullen Root founded The Woodmen of the World (WOW) in the early 1890s. It was essentially a mutual aid society, a beneficiary order that provided death benefits and grave stones to its members by essentially passing around a hat.

That turned out not to work exactly, and so shifted thirty years later to become a regular life insurance company. By 1901 it was the largest fraternal organization in Oregon with 140 camps and a membership of 15,000. Membership conditions: you had to prove yourself in various ways, be older than 16 and – White. A subdivision, Women of Woodcraft, is captured in this photograph.

Would Butler be turning in her grave, surrounded by valkyries like these? Likely not. She would point to the importance of the idea of mutual aid, and to change: if you look at the website of the WoodmenLife Insurance Company that grew out of WOW, you find images of Black, Asian, Brown and other faces among the White beneficiaries, carefully assembled to stress diversity. It might only be on the surface, who can tell, but change nonetheless. And in any case – she might stay silent, but her work speaks to millions, in contrast to the wood people of the world….

***

This brings me to the reason why I, an old White European woman who can take privilege seemingly for granted, am so preoccupied with a Black writer who envisioned change and imbued her heroines with strength and refusal to give up, forever pursuing humanistic goals. She instills hope.

I feel like living in an era where, here as well as internationally, change is pursued or co-opted to move us backwards. The powers that be (or wannabe) want to affirm or re-install structures – and I mean STRUCTURES – that go beyond individual racist impulses or acts, to dominate on top of a hierarchy and use that dominance to extract riches and suffering. These forces are insisting that “differences”exists, be they racial, religious, gender, sexuality or simply cultural. Don’t ever believe in equality! Put a value label to these differing categories, with some “better,” others “worse,” with the dominant category, of course, being the superior one. This valuation is extended to an entire group, depreciating not just single humans, but a whole category. “Negative valuation imposed upon that group becomes the legitimization and justification for hostility and aggression. The inner purpose of this process is social benefit, self-valorization, and the creation of a sense of identity for the one through the denigration of the other. And as is evident, the generation and expression of hierarchy run through it from beginning to end.” (Ref.)

Whether you look at the Nazi play book, present-day Hungary, Russia, India or other authoritarian movements, these principles are at work every single time, with the content attached to the “difference” changing according to local need du jour and historical hierarchies, including colonialism. In addition, progressive movements so often weaken themselves by intra-group strife instead of collaborative fighting against a common enemy. I can think of no better explanation of those principles than in Arundhati Roy’s speech last week at the Swedish Academy.

It is so easy to lose hope, to withdraw by feeling overwhelmed, helpless, powerless to achieve true equality. And yet there was a person who faced obstacles beyond description, who believed in hope and the power of community.

Here is someone who put it in words better than I ever could, Jesmyn Ward, a formidable writer in her own right:

“This is how Butler finds her way in a world that perpetually demoralizes, confounds, and browbeats: she writes her way to hope. This is how she confronts darkness and persists in the face of her own despair. This is the real gift of her work… in inviting her readers to engage with darker realities, to immerse themselves in worlds more disturbing and complex than our own, she asks readers to acknowledge the costs of our collective inaction, our collective bowing to depravity, to tribalism, to easy ignorance and violence. Her primary characters refuse all of that. Her primary characters refuse to deny the better aspects of their humanity. They insist on embracing tenderness and empathy, and in doing so, they invite readers to realize that we might do so as well. Butler makes hope possible.”

Against the backdrop of a legacy of trauma she provided us with a legacy of optimism, that the lessons of successful collective action and resistance in the past will guide us to the right kind of change in the future, with the help of courageous and resourceful Black women.